Afghanistan and Central Asia: Pragmatism Instead of Illusions

“When the winds of change blow, some build walls, others build windmills.” — Chinese proverb

Afghanistan remains one of the most complex and controversial spots on the map of Eurasia. After the Taliban came to power in 2021, it seemed the countries of Central Asia were faced with a choice: to distance themselves from the new regime or cautiously engage with it. However, it appears they have chosen a third path – pragmatic cooperation free from political intentions.

Today, a window of opportunity is opening for the Central Asian states to reconsider their relationship with Afghanistan, not as a buffer zone or a source of instability, but as a potential element of a new regional architecture.

At the same time, these countries are in no hurry to establish close political ties with Kabul. They avoid making declarations about “integrating” Afghanistan into Central Asia as a geopolitical region. Instead, the focus is on practical, rather than political or ideological, cooperation in areas such as transportation, trade, energy, food security, and humanitarian engagement.

This pragmatic approach is shaping a new style of regional diplomacy, which is restrained yet determined. Against this backdrop, two key questions emerge: What role can Afghanistan play in regional development scenarios, and what steps are needed to minimize risks and maximize mutual benefit?

Afghanistan After 2021: Between Stability and Dependency

Since the end of the war and the Taliban’s return to power, Afghanistan has experienced a degree of relative order. However, the country remains economically and institutionally dependent on external assistance. Historically, Afghanistan has survived through subsidies and involvement in external conflicts, from the “Great Game” to the fight against international terrorism. Today, new actors, such as China, Russia, India, Turkey, and the Arab states, are stepping onto the stage alongside Russia, the United States, and the broader West.

In the context of current geopolitical realities after the fall of its “democratic” regime, Afghanistan has found itself in a gap between the experiences of the past and a yet undetermined future. It has a unique opportunity to transcend its reputation as the “graveyard of empires” and determine its fate while simultaneously integrating into the international community. How the de facto authorities in Afghanistan handle this opportunity will not only shape the Afghan people’s and the region’s future but also influence the development of the entire global security paradigm.

In parallel, the countries of Central Asian are building bilateral relations with Kabul on strictly pragmatic terms: participation in infrastructure and energy projects, food supply, and humanitarian aid. All of these steps have been taken without political commitments and without recognizing the regime.

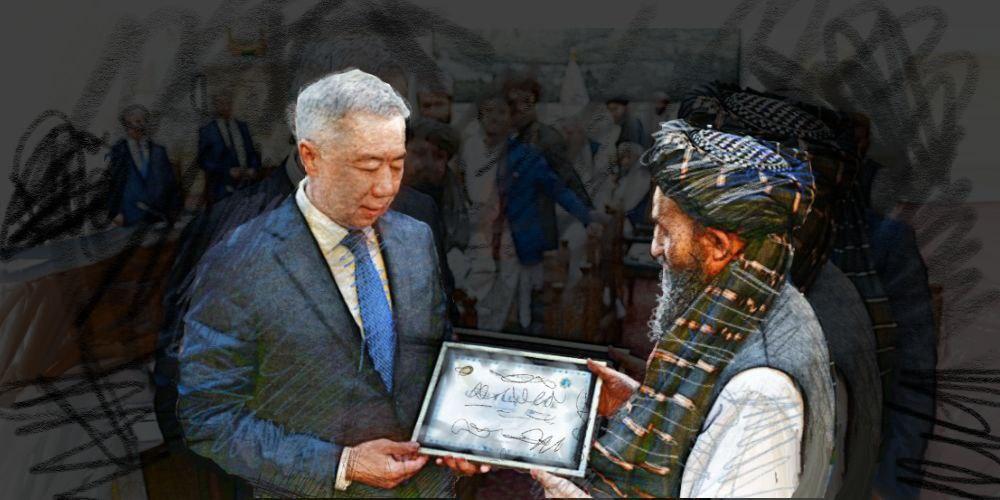

The border between Afghanistan and Tajikistan near Khorog, GBAO; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

Geo-Economics and Logistics: Afghanistan as a Strategic Hub

The regional reality in Central Asia is increasingly taking on a geo-economic dimension. The region is not only an arena for the interests of external powers but also a zone for developing transport, logistics, and energy networks in which Afghanistan is playing an increasingly prominent role.

Currently, four of the six corridors under the Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Program (CAREC) pass through Afghan territory, linking it with Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan.

Central Asian countries are paying special attention to infrastructure projects that, under favorable conditions, could reshape the region’s economic landscape. These include the Trans-Afghan railway, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline, and the Central Asia-South Asia power project (CASA-1000).

What is particularly significant is that these projects are beginning to move beyond the conceptual stage.

Recently, the presidents of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan officially inaugurated the 500 kV Datka–Sughd transmission line, a key component of the CASA-1000 regional project. Over the next 15 years, both countries are expected to supply Afghanistan and Pakistan with 23 billion kWh of electricity through this line, marking a major step forward in regional energy cooperation.

The Trans-Afghan Corridor is also beginning to take shape. While its eastern route (via Kabul) faces engineering and financial challenges, the western path (Torgundi–Herat–Kandahar–Spin Boldak) is becoming more defined. The Afghan government recently signed five contracts with domestic companies to design a 737.5 km railway connecting Herat and Kandahar.

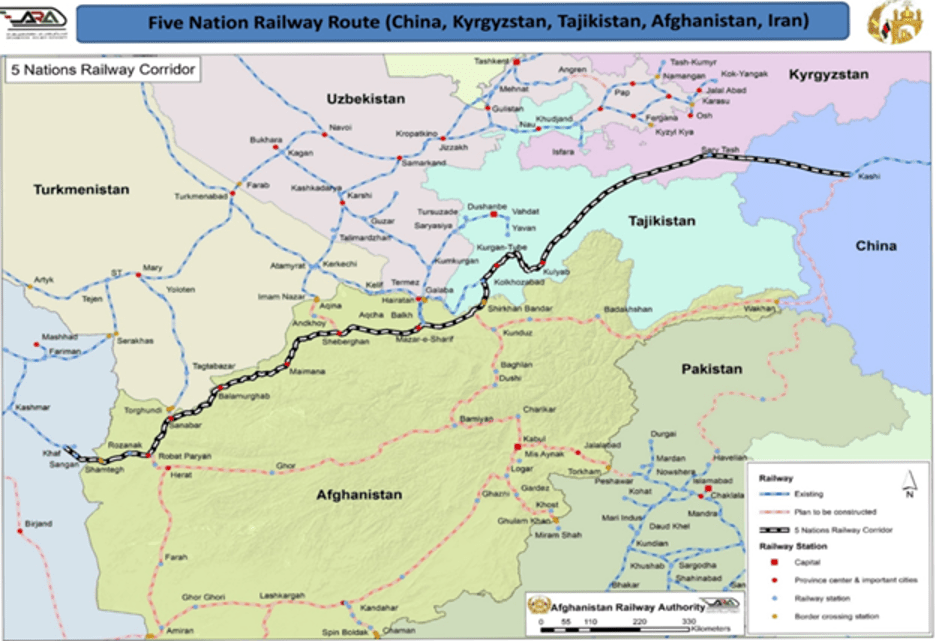

The “five-country corridor” initiative (China-Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan-Afghanistan-Iran), which Tehran is trying to promote, also retains its potential. While it currently exists mostly on paper, the construction of a railway segment from Uzbekistan to Herat and its integration with the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan (CKU) railway would give it practical value as part of a new Eurasian transport network.

Image: Caspian Bulletin

The activity of neutral Turkmenistan in this area also deserves attention. Turkmenistan’s role in the “North-South” and “East-West” logistical intersections makes it one of the key operators in Eurasian traffic, including the Afghan direction. A connection is being formed through Iranian territory, with access to the ports of Bandar Abbas and Chabahar.

However, Ashgabat’s “flagship” project is the TAPI gas pipeline, designed to supply natural gas to countries with a total population of 1.75 billion. As President Berdimuhamedov stated, “Speaking about the TAPI gas pipeline project, I would like to emphasize its high social significance. According to experts, the construction of the pipeline and related infrastructure systems, new institutions, and enterprises will create 12,000 jobs in Afghanistan and solve several key humanitarian issues in the country.”

Alongside the implementation of the TAPI project, Turkmenistan is also building power transmission lines and an optical fiber communication system along the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan route. A 214-kilometer section of the pipeline has already been built in Turkmenistan. Last September, the construction of a 153-kilometer section from Serhetabad to Herat was launched. The construction is now ongoing in Afghanistan, where ten kilometers have already been built.

In addition to the countries of Central Asia, external actors are also showing interest in developing trans-Afghan routes. India, using the Iranian port of Chabahar, is seeking direct access to the markets of Afghanistan and Central Asia, bypassing Pakistan. This direction is seen by New Delhi as a strategic alternative to the China-Pakistan corridor.

Russia, in turn, links the development of Afghan logistics with the implementation of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which connects Russia with Iran and then, via Chabahar, to South Asia. Integrating Afghan transit into this route can provide additional flexibility and a regional dimension to the INSTC.

All this opens up opportunities for transregional connections, where Afghanistan serves not as a point of fracture, but as a connecting link between South, Central, and Western Asia.

There is a political saying: “If you’re not at the Table, you’re on the Menu.” For Central Asia, participation in new corridors is not a choice but a matter of survival; either you are the route, or you are a transit territory without rights.

However, Afghanistan’s potential is not limited to transit. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), copper reserves at the Aynak deposit exceed 660 million tons of ore with a metal content of 1.67%, corresponding to about 11 million tons of copper. This makes it one of the largest undeveloped copper projects in the world. Iron ore reserves at Hajigak reach 2 billion tons with iron content up to 64%. Additionally, the USGS has recorded significant resources of lithium, beryllium, tantalum, and other rare earth elements, especially in the southwestern and northeastern provinces. According to their forecasts, Afghanistan could occupy a leading position in the world in terms of lithium potential.

However, despite the availability of these reserves, sectoral problems remain significant: lack of infrastructure, regulatory instability, absence of a transparent licensing distribution mechanism, and field commanders having control over mining operations. Due to these factors, the potential major industrial projects, Aynak and Hajigak, are essentially suspended. Despite this, an eventual wave of bidders is anticipated.

At the same time, smaller but more practically oriented projects are gaining momentum, including the construction of power grids and small hydropower plants, warehouses, and Afghan companies’ participation in agricultural programs. This is the level of cooperation where concrete solutions can be realized.

Thus, the development of Afghanistan’s infrastructure opens a window of opportunity. The country is transforming from a “buffer zone” into a geoeconomic link between Central, South, and Western Asia. At the same time, this is a space of high sensitivity: growing activity here requires coordination among the Central Asian countries to avoid duplication, enhance stability, and prevent rivalry.

Yes, Afghanistan remains a complex partner, but ignoring its geoeconomic link means losing a key element of the new Eurasian economic framework.

Of course, structural barriers remain, such as the Afghan-Pakistani conflict, lack of international recognition, and the sanctions regime. Nevertheless, the countries of Central Asia, with the support of their surrounding environment, continue to view Kabul as an important economic neighbor.

Security and Ideology: The Region’s Cautious Vigilance

Despite signs of stabilization within Afghanistan, the Central Asian states maintain a cautious stance on issues of security and ideological influence from the Taliban. Of particular concern are reports of the presence in Afghanistan of militants from transnational groups with a Central Asian orientation. Although the Taliban claims to have control over the situation, most regional experts acknowledge the long-term risks involved.

There is also some unease about the development of religious infrastructure, including a network of madrasas, including those known as “jihadist madrasas.” These institutions could potentially form an ideological base beyond Afghanistan’s borders.

Nevertheless, the Central Asian countries have avoided alarmism, focusing on dialogue and taking a realistic approach to the assessment of threats.

Afghanistan as Part of the Regional Consensus

At the first “Central Asia – European Union” summit held in Samarkand, Afghanistan did not occupy a central position on the agenda. Nevertheless, in some speeches, the importance of a stable and engaged Afghanistan was emphasized, not so much as an object of foreign policy, but as part of the broader regional space.

In the final declaration, leaders reaffirmed their commitment to seeing Afghanistan as a “safe, stable, and prosperous state with an inclusive governance system that respects the human rights and fundamental freedoms of all its citizens,” including women, girls, and ethnic and religious minorities.

It is clear that the “gender issue” was included in the declaration at the initiative of the European side since the Central Asian republics have never focused on this problem. As previously reported by TCA, the emphasis on the “gender issue” is not quite what the Central Asian countries expect in the context of the Afghan resolution. For them, it is much more important to address pressing issues such as security, economic cooperation, and migration control, which directly affect stability in the region. This is why Central Asian countries prefer to focus on practical steps and avoid unnecessary politicization of issues that might complicate dialogue with the Taliban and worsen the situation in neighboring Afghanistan.

In this regard, the position of the EU and Central Asian countries on women’s and girls’ rights, as reflected in the Samarkand declaration, should be seen as only “generally aligned.”

The declaration also established a mechanism for regular consultations on the Afghan agenda, stating: “We support the holding of regular consultations between the special representatives and envoys of Central Asian countries and the EU on issues related to Afghanistan.”

These consultations will help adapt regional policy to the new reality where this is no official recognition of the Taliban, but an understanding that, de facto, they are a key link in ensuring access to humanitarian aid and preventing cross-border threats.

Earlier at the Samarkand meetings, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan emphasized in an interview with Euronews that Afghanistan remains one of the priorities of the country’s foreign policy. According to him, the Uzbek approach has always been based on pragmatism and a focus on long-term goals, rather than ideological preferences. Mirziyoyev also noted that “many who disagreed with our policy on Afghanistan are now forced to acknowledge its correctness and inevitability,” referring, among other things, to international partners.

These statements reflect not only Uzbekistan’s position but also illustrate the overall shift in the perception of Afghanistan by the Central Asian states.

Kazakhstan has demonstrated the same approach. Since the Taliban came to power, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has consistently emphasized the need for a multilateral and balanced approach to the Afghan issue. His speeches focus on the integration of Afghanistan into regional and international processes. Kazakhstan supports the international community’s efforts, including under the UN’s auspices, to stabilize the situation, provide humanitarian aid, and launch infrastructure projects. Thus, Kazakhstan is developing a concept of “positive neutrality,” where Afghanistan is seen not as an isolated threat but as a potential partner and a key element of regional stability.

Against this backdrop, it becomes evident that a coordinated and pragmatic approach to the Afghan dossier has emerged in Central Asia. Even countries that previously held more rigid positions, in particular, Tajikistan, are now demonstrating increasing flexibility, both in official statements and in practical cooperation. The focus of the regional approach is gradually shifting from isolation and fears to economic ties, infrastructure, and a shared future that is in the interests of all the countries in the region.

Crossroads

Afghanistan has already become an integral factor in the stability and security of Central Asia. Pragmatic, cautious, and consistent interaction is the formula that the countries of the region are applying to their southern neighbor today.

A stable Afghanistan is not an end goal, but a condition for the long-term development and enhancement of Central Asia’s independent regional position in a changing world through the strengthening of ties and reduction of threats.

History has repeatedly tried to turn this region into a battleground for external interests, the so-called “Great Game.” However, at the current moment, Central Asia has the opportunity to not just react to the plans of outside powers but to implement its own. Afghanistan, no matter how complex and contradictory it may be, can become part of this shift, not as a threat but as an opportunity. It all depends on by who and how the future of the region is managed.

Thus, Central Asia is not a battleground; it is a crossroads, and crossroads have their own rules.