Located 175 miles north-west of the country’s largest city, Almaty, Kazakhstan’s Lake Balkhash is the fifteenth largest lake in the world. The remains of an ancient sea which once covered vast tracts of land, on its shores in the city of Balkhash, a mixture of around 68,000 mostly ethnic Kazakhs and Russians eke out a living, predominantly through fishing and mining. But like its’ sister body of water, the Aral Sea, Lake Balkhash is under threat with its inflow sources diminishing.

Fed by glaciers in Xinjiang, China, the Ili River has traditionally accounted for the vast majority of Lake Balkhash’s inflow, but according to research, as of 2021 China was blocking 40% of the river’s inflow, leading to a rise in anti-Chinese sentiments in Kazakhstan.

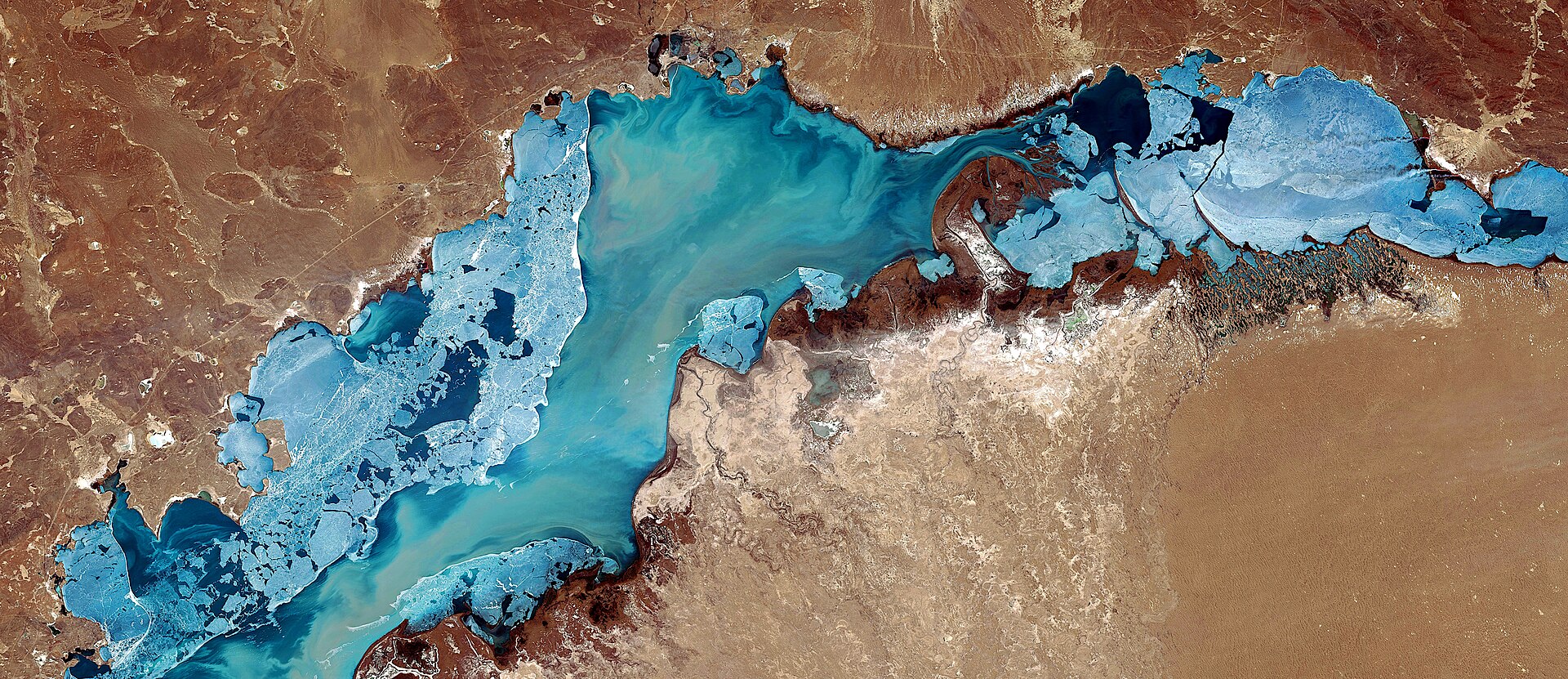

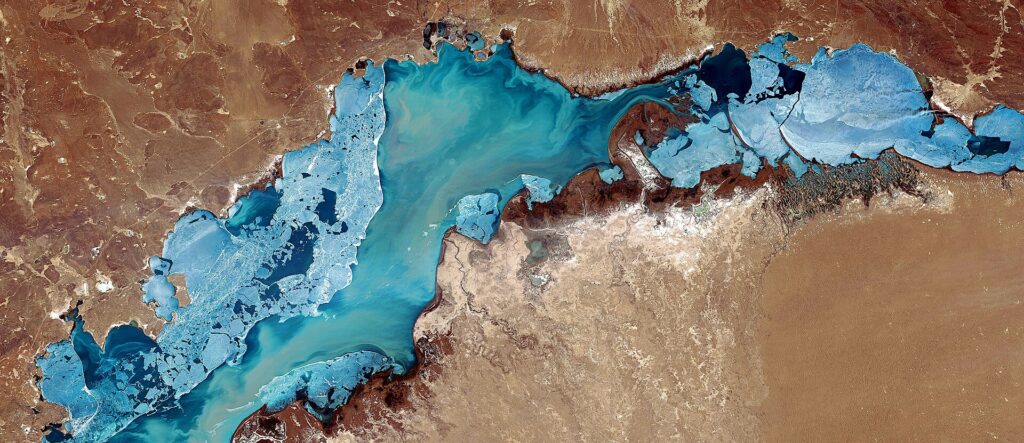

In 1910, Lake Balkhash had an estimated surface area of 23,464 km². As recently as the 1960s, fishermen were netting a catch of over 30,000 tons annually, but by the 1990s, this had fallen to 6,600 tons of significantly less sought-after types of fish. Between 1970 and 1987 alone, the water level fell by 2.2 meters, with projects aimed at halting this decline abandoned as the Soviet Union fell into stagnation before dissolving. Currently, the lake covers a surface area of between 16,400 and 17,000 km². Falling water levels have also led to the appearance of new islands and impacted biodiversity, with 12 types of bird and 22 vertebrates indigenous to the region listed in the Red Book of Kazakhstan as endangered, whilst the Caspian tiger is, in all likelihood, extinct. Meanwhile, contamination from mining, both local and upstream in China, have led to the lake being classified as “very dirty.”

With desertification now affecting one-third of the Balkhash-Alakol Basin, which includes Almaty, the resultant dust storms are leading to an increase in the lake’s salinity, with silt from these storms further affecting inflow. Parallels to the Aral Sea – arguably the worst man-made environmental disaster in modern history – are all too apparent.

Spanning across Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the Aral Sea was once the fourth largest inland body of water in the world, covering 68,000 km². The destruction of the Aral Sea first dates back as far as the U.S. Civil War, when, finding his supply of American cotton under threat, the Russian tsar decided to use the sea’s tributaries to irrigate Central Asia and create his own cotton bowl. With 1.8 million liters of water needed for every bale of cotton, the water soon began to run out. By 2007, the Aral had shrunk to one-tenth its original size.

Up until the late-1990s, the land surrounding the Aral Sea was still cotton fields; today, it’s largely an expanse of salinized grey emptiness. The desiccation of the landscape has led to vast toxic dust-storms that ravage around 1.5 million square kilometers. Spreading nitrates and carcinogens, these storms – visible from space – used to occur once every five years, but now strike ten times a year.

Once a thriving agricultural center, Karakalpakstan, home to the remaining section of the so-called Large Aral Sea, is now one of the sickest places on Earth. Respiratory illness, typhoid, tuberculosis and cancers are rife, and the region has the highest infant mortality rate in the former USSR.

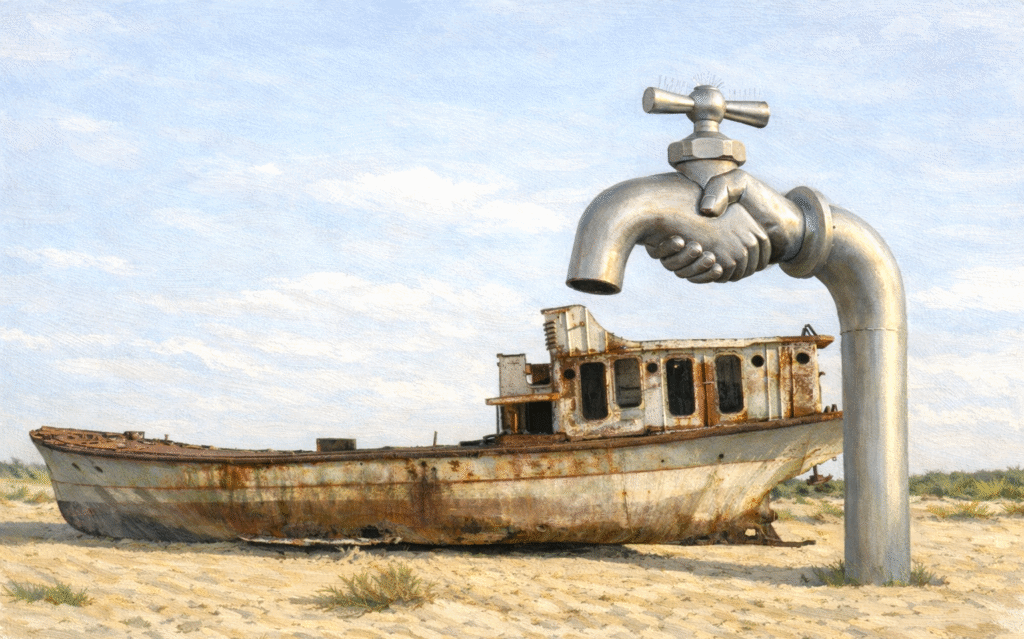

Further into the manmade desert lies the forgotten hamlet of Moynaq. At its peak, the town was home to 60,000 people, mostly fishermen and their extended families, with the Aral Sea producing up to 30% of the Soviet catch and saving Russia from widespread famine in the 1920s. Accessible only by air and ferry well into the 1970s, Moynaq also served as a popular beach resort for well-heeled bureaucrats, its airport hosting fifty flights a day at its peak. By the eighties, though, tourism had dried up. Digging channels through the sand in pursuit of the diminishing sea, Moynaq’s fishermen discarded their ships where they became grounded. With the sea’s major source, the Amu Darya River no longer reaching its historic terminus, a local saying goes: “When God loved us, he gave us the Amu Darya, when he ceased to love us, he sent us Russian engineers.”

Today, the town’s population number less than 2,000, the remnants of the sea almost two hundred kilometers away. Striped sunlight spills through the skeletal ribs of the desert ships hulls, sunbaked trawlers slowly oxidizing. Animated by history, these inert objects take on an ethereal vitality in opposition to the overwhelming sense of desolation surrounding them. Thorny grey and fuchsia pink thistles destined to become tumbleweeds shake as brackish gusts whip across the vast wasteland once so teeming with life. With the sea gone, the region is subject to searing summers and freezing winters, 500 species of bird, 200 mammals, a hundred types of fish and countless insects unique to the region all now extinct.

“Like its more notorious sibling, the Aral Sea, Lake Balkhash is an inland endorheic lake threatened by unsustainable human exploitation of its feeder river systems,” Dr. Kristopher White, an Economic Geographer and Associate Professor at KIMEP University in Almaty told The Times of Central Asia. “Also like the Aral, deficit conditions currently prevail with respect to Balkhash’s water balance. This means that inflow from the four river systems – plus other additions from precipitation on the surface and runoff – is less than the net losses resulting from evaporation from the lake’s surface plus any groundwater seepage.

“The main concern in this equation is the Ili River, which is responsible for approximately 75% of Balkhash’s water additions. That the headwaters of the Ili lie in China makes the river a geopolitically sensitive trans-boundary waterway. Dams, canals, and water withdrawals on the Chinese side have powered agricultural and industrial development in Xinjiang. As with other trans-boundary river systems, actions taken in ‘upstream’ States often negatively impact populations and aquatic ecosystems ‘downstream,’ as Kazakhstan is in this case. Being reliant upon decisions made in China, particularly those requiring the consideration of ecological integrity and sustainable use of riparian resources, has led to significant apprehension in Kazakhstan.”

Whilst organizations such as the Save Lake Balkhash International Research Project are campaigning for the designation of a “special status which legally protects lake’s ecosystem and people inhabiting lake area,” with a referendum set to be held on the construction of a nuclear power plant that would likely use water from the lake as a coolant, the situation for remains dire. Whether Lake Balkhash can be saved or is set to mirror the fate of the Aral Sea remains to be seen.