Afghans who fled to Tajikistan are keeping a low profile lately.

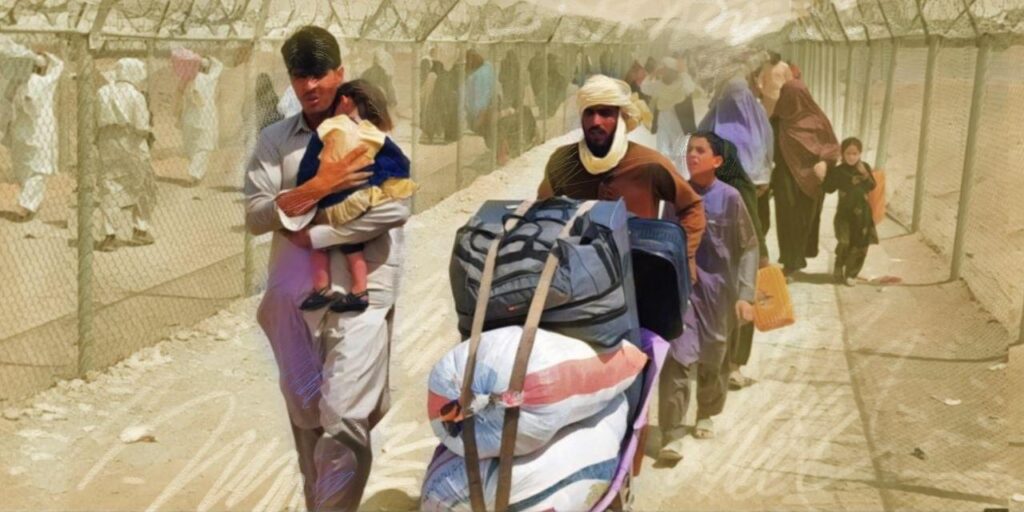

Tajik authorities have started the latest wave of deportations, and this one looks to be bigger than the previous sweeps.

“You Have 15 Days”

At the beginning of July, Afghan refugees and asylum-seekers in Tajikistan received an SMS warning them to leave the country within 15 days or else they would be forcibly deported. Tajikistan’s government has not commented on these messages, but the detention of Afghans started not long after the messages were sent.

So far, the only two places mentioned where Afghans were being apprehended were the Rudaki district outside of Dushanbe and the town of Vahdat, 26 kilometers from Dushanbe. Hundreds of Afghan refugees are known to be living in these two areas.

Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s Tajik Service, known locally as Ozodi, reported that journalists who went to the houses of Afghan refugees in Vahdat were stopped and turned away by men in military uniforms outside the homes. Some Afghan refugees in Vahdat spoke with Ozodi under the condition of anonymity and said that on July 15, several vans arrived and took away “dozens” of Afghan men, women, and children.

One said Afghan refugees are staying inside their homes, fearing that if they go out, they will be detained and deported. Police “take the documents from Afghans and set a date for them to leave the country,” the refugee said, “For more than 20 days we have practically not stepped outside at all.”

Local Tajiks confirmed that Afghans were being taken away and that many of those who remained were searching for new places to live to avoid being apprehended.

The Tajik authorities did not say anything about the deportations until July 19, when the state news agency Khovar posted a text from the Press Center of the Border Troops of the State Committee for National Security. The statement said some “foreign citizens” had entered Tajikistan illegally, and a “certain number” of them engaged in illegal activities such as “narcotics trafficking, [spreading] the ideas of extremist movements,” or providing false information or documents to acquire refugee status.

The office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) said that as of the end of 2024, there were 9,902 Afghan refugees registered in Tajikistan. However, Afghans have been fleeing their homeland and coming to Tajikistan for many years, and some estimates for the number of Afghans in Tajikistan run as high as 13,000.

Something else which remains unclear about the Afghan refugees in Tajikistan is how many are ethnic Tajiks. Ostensibly, most of them could be since the ethnic Tajik population of Afghanistan is mainly found in areas adjacent to Tajikistan. Many who came to Tajikistan 10 or 15 years ago have assimilated and are likely not refugees or asylum seekers, but may not have obtained Tajik citizenship.

It is unclear how many Afghan citizens have been detained and deported since the start of July, but they are just the latest to be sent back to Afghanistan in recent years.

Earlier Waves of Deportations

On August 25, 2022, the UNHCR raised “grave concerns over the continued detention and deportations of Afghan refugees in Tajikistan.” The UNHCR said that on August 23, Tajik authorities sent five Afghan families back across the border. By September 6, the number of Afghans deported had reached 85. The UNHCR’s Director of International Protection, Elizabeth Tan, called at the time for Tajikistan to “stop detaining and deporting refugees, an action that clearly puts lives at risk.”

During the first week of December 2024, the Tajik authorities deported at least 56 more Afghans, most from the Rudaki district and Vahdat. The UNHCR again appealed to the Tajik government to halt deportations, noting it was “the third documented incident of forcible returns to Afghanistan since October 2024.”

In January 2025, the UNHCR said that at least 80 Afghans had been deported during the last month of 2024.

Grim Future, Forgotten Past

The UNHCR, rights groups, and others have pointed out that some of those being deported are employees or military personnel from the ousted Afghan government who could face ill-treatment and possibly execution back in Afghanistan.

As the government of former Afghan President Ashraf Ghani was falling in mid-August 2021, as many as 18 Afghan aircraft flew to Tajikistan with government officials, soldiers, and their families aboard. Some later departed Tajikistan for third countries, but many of those who escaped Afghanistan in August 2021 remained in Tajikistan.

Even for those who are not former government employees or soldiers, returning to Afghanistan is a journey into hunger and poverty.

Afghanistan has been unable to feed the people who remained in the country after the change in power. In 2024, the UN Development Programme said that 85% of Afghanistan’s people live on less than a dollar a day. In June 2025, the World Food Program stated that 15 million of Afghanistan’s roughly 40 million people face severe hunger.

In the first six months of 2025, Iran deported some 1.5 million Afghans back to Afghanistan, 410,000 of them since the end of the Israeli-Iran war in June. During the same period, Pakistan deported more than 300,000 Afghans. Every returning citizen places further strain on already insufficient food supplies, and few if any of those being deported are likely to find gainful employment. And Iran and Pakistan have better relations with the Taliban-run government in Afghanistan than Tajikistan does.

The Tajik authorities still view the Taliban as a threat, and Tajikistan is the only immediate neighbor of Afghanistan that has not established a dialogue with the Taliban government. The Afghan embassy in Dushanbe is still staffed by personnel from the ousted regime of Ashraf Ghani. Those being returned from Tajikistan could face a particularly bleak reception back home.

The Tajik border guards’ July 19 statement about deporting Afghans started with the words, “Due to the difficult political and economic situation in the region and the world, there has been an increase in the migration of foreign citizens to our country.”

The bitter irony is that some 30 years ago, the situation was the reverse. During Tajikistan’s civil war from 1992-1997, hundreds of thousands of people from Tajikistan fled the country. The June 1997 Tajik Peace Accord ended the war, and the repatriation of Tajik refugees started.

Russia’s border guards kept watch on the Tajik-Afghan frontier until 2005. They oversaw the return of Tajik refugees from Afghanistan after the civil war ended. By October 1999, the Russian border guards reported that more than 150,000 Tajik refugees had returned from Afghanistan since the peace accord was signed.

With this in mind, the actions of the Tajik government today in returning Afghan refugees and asylum-seekers seem particularly harsh.