The UN Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belém, Brazil, concluded with a hard-fought global deal that boosts climate finance for developing countries but avoids any promise to phase out fossil fuels. Amid this uneasy compromise, the Central Asian nations worked to get their priorities heard. Their delegations pressed for more climate funding, recognition of their unique vulnerabilities, and support for regional initiatives, with mixed results.

A United Regional Voice on Climate

Home to over 80 million people, Central Asia entered COP30 with a goal outlined as “five countries, one voice,” after a regional dialogue in Dushanbe ahead of the summit forged a common stance on shared threats such as melting glaciers and water stress. The region has already warmed about 2.2 °C – faster than the global average – and glaciers are shrinking by roughly 0.5% each year, Uzbekistan’s environment minister Aziz Abdukhakimov warned in Belém. He noted worsening land degradation and vanishing water resources, underscoring Central Asia’s acute climate vulnerability. In response, Uzbekistan unveiled a new pledge to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 50% by 2035 (from 2010 levels) by expanding renewable energy and forests. Such actions align with COP30’s call for developed nations to triple adaptation finance by 2035 to help vulnerable countries cope. “COP30 showed that climate cooperation is alive and kicking, keeping humanity in the fight for a livable planet,” UN climate chief Simon Stiell said in his closing speech, praising delegates for persisting despite global divisions.

National Commitments and Initiatives

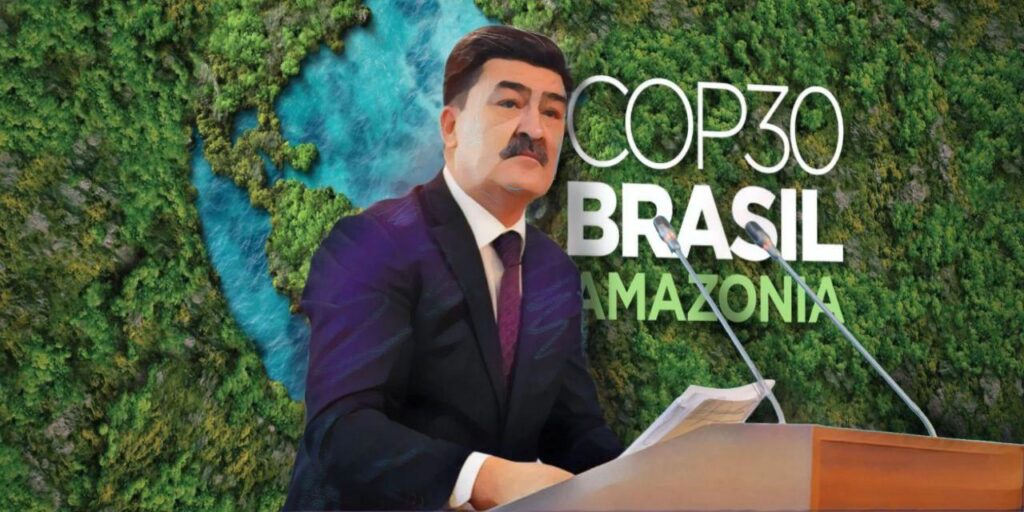

Kazakhstan, Central Asia’s largest economy and emitter, took on a visible role at COP30. Its delegation was led by Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources Yerlan Nyssanbayev, who addressed the summit’s opening session. Nyssanbayev reaffirmed Kazakhstan’s commitment to the Paris Agreement goals, noting the country has adopted a “Revised Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) and a National Adaptation Plan” with more ambitious targets to cut emissions and bolster resilience. “It is crucial for us to consistently work toward achieving our climate goals,” he stated.

Nyssanbayev emphasized the importance of climate finance for developing countries, highlighting the new “Baku–Belém Roadmap” to mobilize $1.3 trillion annually by 2035 and urging support for a significantly increased funding mechanism. Kazakhstan also became one of only seven nations – and the sole Central Asian country – to sign a joint declaration pledging “near zero” methane emissions from its fossil fuel sector. In a sign of ongoing regional leadership, Nyssanbayev invited all delegates to attend a Central Asia Regional Environmental Summit that Kazakhstan will host in 2026, aiming to sustain climate cooperation beyond COP30.

Kyrgyzstan, given its geography, used the summit to champion the mountain agenda and the plight of high-altitude communities on the frontlines of climate change. The Kyrgyz Republic chairs the UNFCCC’s Mountain Group and sent a delegation led by Deputy Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers, Edil Baisalov, and Dinara Kemelova, the President’s Special Representative for the Mountain Agenda. In the first week of COP30, Kemelova delivered keynote remarks at multiple high-level sessions, calling for strengthened international support and financing for mountain regions. She emphasized that Central Asia’s “water towers” – its glaciers and snowpack – are rapidly receding, threatening water supplies and biodiversity, and requiring coordinated action by all UNFCCC parties.

On November 14, Kyrgyzstan convened multilateral consultations on mountains and climate change, an initiative that drew backing from over 30 countries and highlighted Kyrgyzstan’s leadership alongside partners with similar geography, including Nepal and Bhutan, to push for greater global recognition of mountain-specific climate risks. While its proposal to establish a Mountain Resilience Hub in Bishkek remains under discussion, the delegation reported growing international support for coordinated action and increased adaptation finance focused on glacier-dependent regions.

A tangible outcome was the signing of a $250 million “Glacier to Farm” project agreement between the Asian Development Bank and Green Climate Fund, aimed at helping farmers and communities in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Pakistan adapt to glacier melt and water stress.

Tajikistan – with over 93% of its terrain dominated by mountains – arrived at COP30 focused on protecting glaciers and water resources. In the first week of the summit, Bakhodur Sheralizoda, head of Tajikistan’s Committee for Environmental Protection, cited outcomes from the UN-backed High-Level International Conference on the Preservation and Protection of Glaciers, held in Dushanbe in May 2025. Sheralizoda told delegates that over 1,000 glaciers in Tajikistan have disappeared in recent decades and warned of severe regional water stress. Despite contributing minimally to global emissions, Tajikistan is highly vulnerable to changes in glacial runoff and river flow.

At COP30, the delegation presented its national “Green Tajikistan” program, which aims to plant two billion trees by 2040 to combat erosion, restore degraded land, and sequester carbon. Sheralizoda also highlighted Tajikistan’s success in having 2025 declared the UN International Year of Glacier Preservation, urging stronger global commitments to fund climate adaptation and cryosphere research.

Uzbekistan used the summit to showcase new climate targets and policy progress. Delegates reported that the country has submitted an updated NDC as part of its long-term strategy to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. The revised NDC outlines stronger commitments tied to Uzbekistan’s “Green” Economy framework, including plans to expand renewable energy, improve energy efficiency, and restore degraded land. That pledge includes a target of 12,000 MW of renewable energy capacity by 2030 and plans to double energy efficiency across key sectors.

In Belém, Uzbekistan also promoted its national afforestation initiative, which is seeking to expand forest cover to 6.1 million hectares, including in the degraded Aral Sea zone, and increase protected areas to 14.5% of national territory. The Uzbek delegation emphasized the need for climate finance to support these projects and called for international partnerships to accelerate implementation.

Turkmenistan, one of the world’s largest methane emitters, participated in COP30 as part of the Central Asian bloc. While the country did not announce new targets, its delegation engaged in discussions on methane reduction and water resource management. Although Turkmenistan has not joined the Global Methane Pledge, it has taken nascent steps and has begun work with UNEP and the Global Methane Initiative to assess and mitigate emissions from its energy sector. Its participation in regional climate meetings signals a growing awareness of the risks it faces and the international scrutiny it draws. Turkmen officials voiced support for continued dialogue on water security and renewable energy in Central Asia.

In 2023, Turkmenistan published its first National Youth Climate Statement with support from the UN, reflecting growing public engagement on climate issues and younger generations’ calls for sustainable development and resilience.

Calls for Support and Next Steps

Throughout the summit, the Central Asian countries called for expanded international support. The final COP30 agreement encourages developed nations to triple adaptation finance by 2035, a provision regional leaders welcomed, given their shared exposure to glacial loss, drought, and extreme heat.

Regional efforts such as the Central Asia Climate Dialogue and the Regional One Health Coordination Council – which links environmental and health sectors – have gained momentum in recent years, and were referenced by stakeholders in COP30 side events. They also stressed that collective financing and technology transfers are essential if their countries are to meet targets under the Paris Agreement.

In his address, Kyrgyz Minister of Natural Resources, Meder Mashiev, underscored the country’s specific challenge, stating that Kyrgyzstan is a country with “low emissions but high climate vulnerability.” While other Central Asian nations face different climate pressures, from the high Pamirs to the Aral Sea basin, the overriding message emanating from Central Asia in Belém was clear: they are committed to action, but can’t do it alone.