Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev announced his reform plans on January 20, including structural changes to the government. Arguably, one of the least consequential of those changes is replacing the current bicameral parliament with a unicameral parliament.

Across Central Asia, over the last 35 years, parliaments have repeatedly switched from unicameral to bicameral parliaments, or vice versa, the number of deputies has increased and decreased, and in some cases, parallel bodies have come into existence and later disappeared.

Kazakhstan

When the Soviet Union collapsed in late 1991, each of the former republics, including the Central Asian countries of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, had a unicameral, republican Supreme Soviet elected in 1990. These Supreme Soviets continued functioning after independence until 1994, and in the case of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, until 1995.

In Kazakhstan, in December 1993, the majority of the 360 deputies in the Supreme Soviet voted to dissolve the body. In March 1994, there were elections to the new parliament (Supreme Kenges) that had 177 seats.

During the tumultuous year of 1995, the parliament was dissolved by then-President Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ruled by decree until snap parliamentary elections in December of that year.

However, on August 29, 1995, voters approved a new constitution in a national referendum. That constitution created a bicameral parliament with 67 deputies in the Mazhilis, the lower house, and 50 deputies in the Senate, 10 of them directly appointed by the president.

Deputies to the Mazhilis were chosen in popular elections. Senators were chosen in indirect elections involving deputies from local, provincial, and municipal councils of large cities.

In the snap parliamentary elections of October 1999, 10 seats were added and chosen by party lists, while the original 67 continued to be contested in single-mandate districts.

That structure lasted until 2007. Constitutional amendments adopted in late May that year increased the number of seats in the Mazhilis to 107, of which 98 were to be chosen by party lists. Nazarbayev’s Nur-Otan party won all 98 of the party list seats in the August elections.

The remaining nine representatives came from the Assembly of Peoples of Kazakhstan, a group representing the various ethnic groups in Kazakhstan that Nazarbayev created in 1995. Eight additional members of the Assembly were given seats in the Senate.

The Assembly held its own elections to fill those seats.

Kazakhstan conducted a constitutional referendum in June 2022, in part aimed at mollifying discontent that lingered from the mass unrest in early January that year, which left 238 people dead. Some amendments stripped away powers in the executive branch that had accumulated during the 28 years Nazarbayev was president, and more power was given to parliament.

Another amendment removed the nine Mazhilis seats reserved for members of the Assembly of Peoples of Kazakhstan. One amendment reduced the number of Senate members appointed by the president back to 10, after it had been raised to 15 under a 2007 amendment.

Kyrgyzstan

A referendum in Kyrgyzstan on constitutional amendments in October 1994 created a bicameral parliament with 70 seats in the Legislative Assembly, the lower house, and 35 in the Assembly of People’s Representatives, the upper house. Kyrgyzstan’s first parliamentary elections were held in February 1995.

When the 2000 parliamentary elections came around, the number of seats was slightly altered: 60 in the Legislative Assembly, and 45 in the Assembly of People’s Representatives.

The referendum of 2003 changed the structure again, creating a unicameral parliament with 75 seats for the 2005 elections.

In October 2007, another constitutional referendum enlarged parliament to 90 seats and stipulated that they all would be filled in elections by party lists.

In June 2010, less than three months after Kurmanbek Bakiyev was ousted as Kyrgyzstan’s president, a referendum was conducted that changed Kyrgyzstan’s form of government from presidential to parliamentary and increased the number of deputies to 120.

Kyrgyzstan’s 2020 parliamentary elections were rife with accusations of vote-buying, gerrymandering, and the use of administrative resources to fill parliament with presidential loyalists. The results announced in October supported these suspicions. That sparked unrest in the capital, Bishkek.

Sooronbai Jeenbekov was ousted as Kyrgyzstan’s president in October 2020 and quickly replaced by Sadyr Japarov, Kyrgyzstan’s current president.

A referendum in April 2021 approved turning Kyrgyzstan back to a presidential form of government, with Japarov arguably enjoying greater powers than any previous Kyrgyz president. The referendum also reduced the number of seats in parliament back to 90.

Another amendment in that referendum raised the status of Kyrgyzstan’s People’s Kurultai to a “public representative assembly… a deliberative, supervisory assembly, making recommendations on areas of social development.” A Kurultai is an ancient Turkic and Mongol tradition of assembling communities, or representatives of communities, to discuss important matters, including the selection of new leaders.

In Kyrgyzstan, national Kurultais have been called previously, usually during times of great social tension or by Kyrgyz presidents seeking support from a group that is supposed to represent traditional Kyrgyz values. The status of Kyrgyzstan’s People’s Kuriltai under the current constitution is not clearly defined, but some see it as potentially a parallel structure to parliament.

Parliamentary elections in November 2021 were decided under a split-system of 54 seats contested by party lists and 36 in single-mandate districts. In the November 2025 elections, single-mandate districts filled all 90 seats.

Tajikistan

Less than a year after it became independent, there was a civil war in Tajikistan that lasted until June 1997.

The Supreme Soviet remained until 1995, and after the post of president was removed in November 1992, the chairman of the Supreme Soviet, at that time Emomali Rahmon (Rahmonov), was made the head of state.

A referendum in November 1994 approved a new constitution that created a 181-seat unicameral parliament, and elections for that parliament were held in February 1995.

The Tajik Peace Accord was signed on June 27, 1997, ending the civil war.

In 1999, a new constitution established a bicameral parliament with 63 seats in the Majlisi Namoyandagon, the lower house of parliament, elected by party lists, and 33 seats in the Majlisi Milli, the upper house, elected by representatives of city, regional, and district administrations.

That arrangement has endured to this day.

Turkmenistan

The constitution that Turkmenistan adopted in May 1992 created a parliament with 50 seats, and that number remained until the 2008 parliamentary elections.

However, after a November 2002 attack on President Saparmurat Niyazov’s motorcade, state investigators said the organizers of the attack planned to kill Niyazov, then convene parliament to approve new leadership.

In August 2003, Niyazov increased the powers of a consultative body called the Halk Maslahaty (People’s Council) that had previously met once a year to rubber-stamp presidential policies, including making Niyazov “president for life” at a session in 1999.

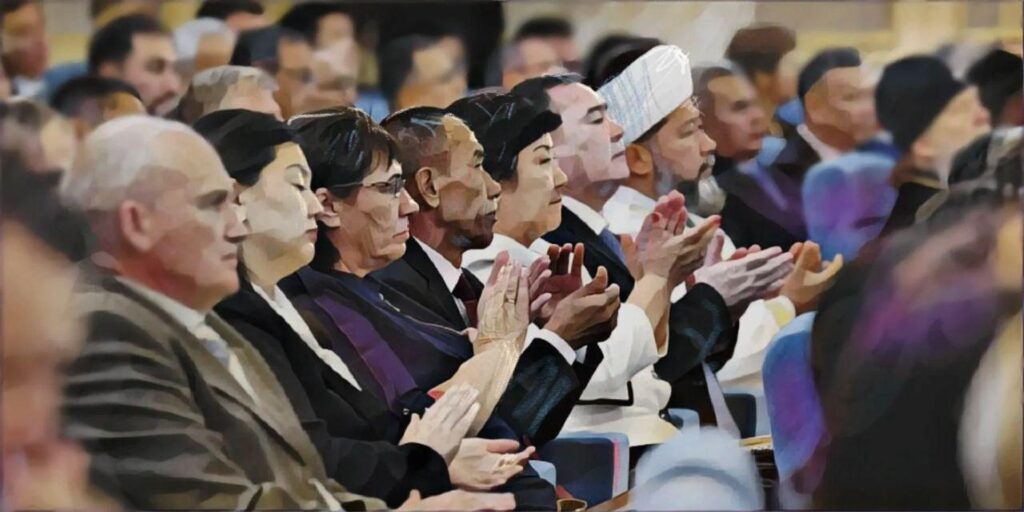

The Halk Maslahaty was comprised of a variety of people: all the parliamentary deputies, local officials, businessmen, religious figures, and others from around the country. More than 2,500 in all. It was therefore impossible to gather them all quickly, and Niyazov subordinated parliament to the Halk Maslahaty.

Niyazov died in December 2006, and his successor, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, introduced amendments to the constitution in September 2008 that abolished the Halk Maslahaty and increased the number of seats in parliament to 125.

The parliamentary elections later in 2008 were also notable for being the first time the ruling Democratic Party of Turkmenistan (formerly the Communist Party of the Turkmen SSR) faced competition. The government created two new parties to give the appearance of conducting competitive elections.

The number of parliamentary seats remained 125, but in 2017, Berdimuhamedov told a meeting of the Council of Elders that he was reforming the group into a new Halk Maslahaty that includes citizens of different ages.

Changes adopted to Turkmenistan’s constitution in late 2020 led to the creation of a bicameral parliament in early 2021, with parliament becoming the lower house and the Halk Maslahaty the upper house.

Berdimuhamedov stepped down as president in early 2022 after having spent several years preparing his son Serdar to take the post. The elder Berdimuhamedov then took the post of Halk Maslahaty chairman.

In January 2023, parliament amended the constitution. The Halk Maslahaty was made the supreme body in the country, with parliament reverting to its unicameral form, and the Halk Maslahaty’s chairman becoming the country’s most powerful politician, more powerful than the president.

Uzbekistan

Voters in Uzbekistan elected 250 deputies to the unicameral parliament in the elections of 1994 and 1999.

The January 2002 referendum approved the creation of a bicameral parliament with 120 seats in the Oliy Majilis, the lower house, and 100 seats in the Senate, the upper house.

Voters only cast ballots for deputies in the Oily Majlis. In the Senate, 84 members were elected by provincial, district, and city councils, and 16 were selected by the president. They took office after the 2004 elections.

Before the 2009 parliamentary elections, an additional 30 seats were added to the Oliy Majlis. However, 15 of these places were reserved for members of the Ecological Movement.

The Uzbek authorities were pressuring Tajikistan not to go ahead with plans to build a massive hydropower plant (HPP), Rogun, upstream. Uzbekistan’s Ecological Movement was spearheading the criticisms against Tajikistan even before its inclusion in parliament.

Uzbekistan’s first president, Islam Karimov, died in the summer of 2016. His successor, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, reversed Uzbekistan’s position on the Rogun HPP and declared that Uzbekistan would work with Tajikistan to build it.

The first parliamentary elections held after Mirziyoyev came to power were in 2019. Before those elections, the Ecological Movement became the Ecological Party and had to compete for seats in the Oliy Majlis, like the other parties.

Constitutional amendments in 2023 reduced the size of the Senate to 65 members, four from each of Uzbekistan’s 12 provinces, the Karakalpakstan Republic, and Tashkent city, with the president appointing the remaining nine members.

Round in Circles

Kazakhstan’s new unicameral parliament will be called the Kurultai. It will have 145 deputies elected on the basis of party lists. It appears the rule will stand that only candidates from officially registered parties will be able to participate in elections. That is also true in all the other Central Asian states except Kyrgyzstan, the only country that still allows independent candidates to run.

All the Central Asian states have seen their parliaments transformed, expanded, and contracted. Every time, there were reasons given why these changes represented political and social progress. Yet after 35 years, the decisions in each country are still made by one man, the president (or in Turkmenistan’s case, the Halk Maslahaty chairman), and a small inner circle.

The changes coming to Kazakhstan could herald a new era of politics in that country, but in the past, such changes have usually been window-dressing, not substantive political change.