The Future of Transit in Kazakhstan

Increasing the volume of transit cargo through Kazakhstan is a strategic priority for the nation as it aims to become a transportation and logistics hub in Central Asia and the Caspian region, with its railways at the forefront of this effort. TCA spoke with Asem Mukhamedieva, Managing Director for New Projects at KTZ Express JSC, about the company’s current capabilities, prospects, and new projects in this direction.

Kazakhstan’s Role in Transit Cargo

TCA: Kazakhstan, has become a vital land transportation corridor between Asia and Europe. How does Kazakhstan Temir Zholy (KTZ) contribute to further increasing transit cargo, and what trends have you observed?

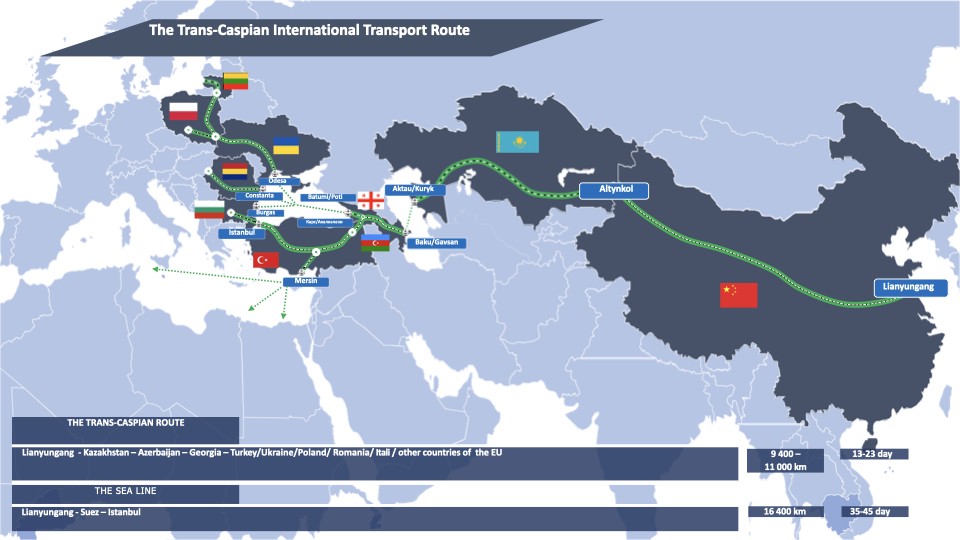

Mukhamedieva- The volume of transit handled by KTZ Express in the first eight months of this year reached approximately 350,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU). The China-Europe-China route saw a 36% increase, while the China to Central Asia route grew by 17%. Notably, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) dispatched 220 container trains, a twenty-fold increase from last year.

TCA: What new routes have been launched, and what is KTZ doing to increase them?

– KTZ is continuously expanding its transportation network and logistics services. One significant development is the Trans-Afghan route, which was launched this May. Under a pilot project, containers with aluminosilicate hollow microspheres were shipped from Pavlodar to Jebel Ali Port via Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the UAE. Offering competitive terms and tariffs has encouraged more cargo traffic along this route.

In July, we cut delivery times in half — down to just five days — on the Xi’an-Altynkol-Tashkent route, compared to the previous 10-12 days. This success is largely due to the new terminal in Xi’an, built by KTZ and its Chinese partners. The terminal consolidates cargo from various Chinese provinces, streamlining logistics processes and significantly improving efficiency.

We also launched several new logistics services to boost cargo traffic and strengthen international links. For example, in June, we introduced a regular South Korea-China-Kazakhstan-Central Asia route. We also reopened a previously unprofitable route from China to Iran and back, reducing costs by collaborating with Chinese partners.

The Growing Importance of the Trans-Caspian Route

TCA: You mentioned the growth of the TITR. Could you elaborate on the regions of China involved, the types of cargo, and what steps are being taken to attract more shipments?

– The Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR) has become a critical link in Eurasian logistics. This year, the route achieved remarkable growth. In September, we welcomed the 200th train dispatched via TITR at the Port of Aktau. Transit volumes for the first eight months of this year surpassed annual totals from previous years. Xi’an province leads in shipments, accounting for 57% of the total volume on this route. Other key provinces include Yiwu, Chongqing, Sanping, and Henan.

Major markets for these shipments are Azerbaijan (62%), Georgia (23%), Turkey (7%), and EU countries (9%). Over 200 different commodity items were transported, with automobiles, components, textiles, and electronics making up 56% of the total.

To maintain this momentum, we are working with all participating countries to reduce delivery times and establish competitive tariffs.

Reducing Delivery Times

TCA: What steps are being taken to further reduce delivery times along these routes?

– The current transit times have been reduced by 2-3 times. For example, cargo dispatched from the Xi’an terminal passes through China in 3-4 days and through Kazakhstan, including trans-shipment at the Port of Aktau, in another four days. Containers arrive in Azerbaijan within 11-12 days and at Georgian ports in 14-15 days.

These impressive results were made possible through the launch of the Xi’an terminal and close cooperation between Kazakhstan Temir Zholy, Chinese railways, and port authorities in Azerbaijan, Georgia, and other TITR participants. To further increase capacity, the governments of Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey signed a Roadmap to synchronize problem-solving along the route. Additionally, unified pricing principles and digitization efforts are underway.

We also launched container shuttle trains on fixed schedules from Altynkol to Poti/Batumi, and from Batumi port to Turkey and Europe. In Aktau, we are developing a container hub to streamline cargo delivery from road and rail to maritime transport.

The North-South International Transport Corridor

TCA: The International Transport Corridor North-South (ITC North-South) is a promising initiative. Can you provide more details on Kazakhstan’s involvement in this project?

– We’re actively working to attract cargo to the eastern branch of the North-South ITC, which opens a direct rail link for goods between Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, India, and Persian Gulf countries. We are establishing a unified logistics operator for this route with Russia and Turkmenistan.

A technical audit was conducted to identify bottlenecks and technological barriers at key rail junctions, leading to a joint action plan for improvements. Kazakhstan, Russia, Turkmenistan, and Iran have also developed competitive tariffs for container and rail car shipments along this corridor.

The Single Digital Window Initiative

TCA: KTZ recently introduced the Single Digital Window (SDW) for customers. Could you explain how it works and what the results are so far?

– The SDW aims to consolidate the services of all KTZ subsidiaries into a single platform, allowing customers to manage logistics more efficiently. Previously, customers had to coordinate separately with each participant in the transportation process, but now everything can be done through the SDW portal or its mobile app, EGOV Business portal, or Single Contact Center.

The project is currently in test mode, and we plan to expand its services to include road, air, and sea transport partners. This integrated system will save customers time and simplify the logistics process.

Challenges and Solutions for Kazakhstan’s Transit Development

TCA: What barriers are hindering Kazakhstan’s transit development, and what measures could enhance it?

– Kazakhstan is already a key transit hub, but as trade volumes grow, we need to strengthen supply chain integration through the development of logistics hubs. Expanding railway infrastructure is crucial, and KTZ has approved a program to enhance existing infrastructure by 2030. This includes repair, modernization, and the construction of new tracks.

Four major projects are underway: the construction of the Dostyk-Moyinty railway line, the third railway border crossing at Bakhty-Ayagoz on the Chinese border, a bypass around Almaty, and the Darbaza-Maktaaral railway line toward Uzbekistan. These projects are expected to significantly increase transit capacity and efficiency.

Kazakhstan’s strategic position and ongoing infrastructure developments position the country as a key player in Eurasian logistics. With ambitious projects and international collaboration, the future of trans-Kazakhstan transit looks bright.