On December 12, 2025, Turkmenistan marks the 30th anniversary of a UN decision granting Turkmenistan the status of a neutral country.

Defining what “permanent neutrality” means for Turkmenistan is impossible, as it is a flexible term used to justify a range of policies, both domestic and foreign. This vague special status has not provided many benefits, but has helped Turkmenistan’s leadership isolate the country and create one of the most bizarre and repressive forms of government in the world today.

Last Item on the Day’s Agenda

On Tuesday, December 12, 1995, the UN General Assembly’s (UNGA) 90th plenary meeting reconvened at 15:20 to consider items 57 to 81 on its agenda. Item 81 was the draft resolution on “permanent neutrality of Turkmenistan.”

The UNGA president at that time, Freitas do Amaral, noted to the Assembly that the draft resolution “was adopted by the First Committee without a vote,” and asked if the Assembly wished “to do likewise.” The Assembly did, and after a few brief remarks about the next Assembly meeting on December 14, the session ended at 18:05.

That is how the UN officially granted Turkmenistan the status of neutrality.

A Great Event

The passing of the resolution on Turkmenistan’s neutrality status might have been a case of going through the motions at the UN, but it was a huge event in Turkmenistan.

Turkmenistan’s first president, Saparmurat Niyazov, had been campaigning internationally for his country to have “positive” neutrality status since 1992. After this was accomplished, Niyazov often proclaimed this special UN recognition as a great achievement for the country and for himself personally.

Ashgabat’s Independence Square, previously known as Neutrality Square and originally as Karl Marx Square; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

December 12 was quickly announced as a national holiday. On the first anniversary of the UN decision in 1996, the former Karl Marx Square in Ashgabat was renamed “Neutrality Square.” Shortly after, an olive branch motif was added to Turkmenistan’s national flag, symbolizing the country’s neutral status.

In 1998, on the third anniversary of UN-recognized neutrality, the 75-meter-high Arch of Neutrality was unveiled in Ashgabat. A 12-meter gold statue of Niyazov that rotated to face the direction of the sun crowned the structure.

Niyazov died in December 2006, and in 2010, the Arch of Neutrality was moved from the city center to the outskirts of the Turkmen capital and unveiled again on December 12, 2011. It has been undergoing renovation and will be unveiled yet again on the 30th anniversary of neutrality.

Former-President Niyazov’s likeness atop the Arch of Neutrality; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

In 2002, Niyazov pushed through a law changing the names of the months of the year and days of the week. December became “Bitaraplyk,” the Turkmen word for neutrality, and continued to officially be called that until 2008, when Niyazov’s successor finally revoked the changes and restored the traditional names.

That successor, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, embraced the special permanent neutrality status and, in 2016, ordered it to be enshrined in the new version of the constitution.

Just after Neutrality Day that year, President Berdimuhamedov reprimanded the minister of culture, two deputy prime ministers, and the head of the state committee on television, radio broadcasting, and cinematography for “failing to control the quality” of the holiday concert dedicated to Neutrality Day that was shown on state television.

Neutrality plays a large role in shaping the country.

In late 1996, Turkmenistan published its new military doctrine, which stated that, as a neutral country, Turkmenistan would not enter into any military alliances, would refrain from using force in international relations, and would not interfere in other countries’ internal affairs.

Niyazov used neutrality to avoid attending summits of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) if cooperation in military or security issues was on the agenda.

Another facet of Turkmenistan’s neutrality involved screening the country from the problems of the outside world. The easiest way to avoid becoming entangled in other countries’ internal affairs and preserve Turkmenistan’s neutrality was to limit contact with citizens of other states and their views of world affairs.

The Turkmen authorities gradually increased restrictions for foreigners to enter the country and cut off, as much as possible, access to foreign media outlets and other sources of information emanating from outside Turkmenistan.

State media is the only officially approved source of media inside Turkmenistan. These outlets, including the newspaper Neutralny (Neutral) Turkmenistan, which rarely reports on major world events, focusing instead on the president’s purported wise leadership in managing domestic affairs and the alleged prosperity of Turkmenistan.

Both these claims have always been questionable to the world outside of Turkmenistan.

In the case of Turkmenistan’s relations with its southern neighbor, Afghanistan, neutrality has proven a useful policy. When the Taliban first came to power in Afghanistan in the late 1990s, Turkmenistan’s government was in contact with the Taliban and their opponents. Afghan peace talks were held in Turkmenistan in 1999.

Turkmenistan did not officially recognize the Taliban, but did allow the Taliban to open a representative office in Ashgabat. While the other Central Asian states were preparing for the worst when the Taliban reached the Central Asian border in the late 1990s, Turkmenistan cited its principle of non-interference in the domestic affairs of another country and took no special measures, despite sharing a 744-kilometer border with Afghanistan.

This policy made it easy for Turkmenistan to maintain a dialogue with whoever was ruling Afghanistan.

There is one other noticeable benefit to Turkmen authorities’ reverence for neutrality. Every year, as Neutrality Day approaches, there is an amnesty given to several hundred prisoners, and many of those released should probably never have been put in prison to begin with. This year, 231 “convicted citizens… who acknowledge their guilt and show sincere remorse” will be freed.

An International Occasion

This year’s anniversary celebration should feature some prominent guests, though an official list has not yet been released.

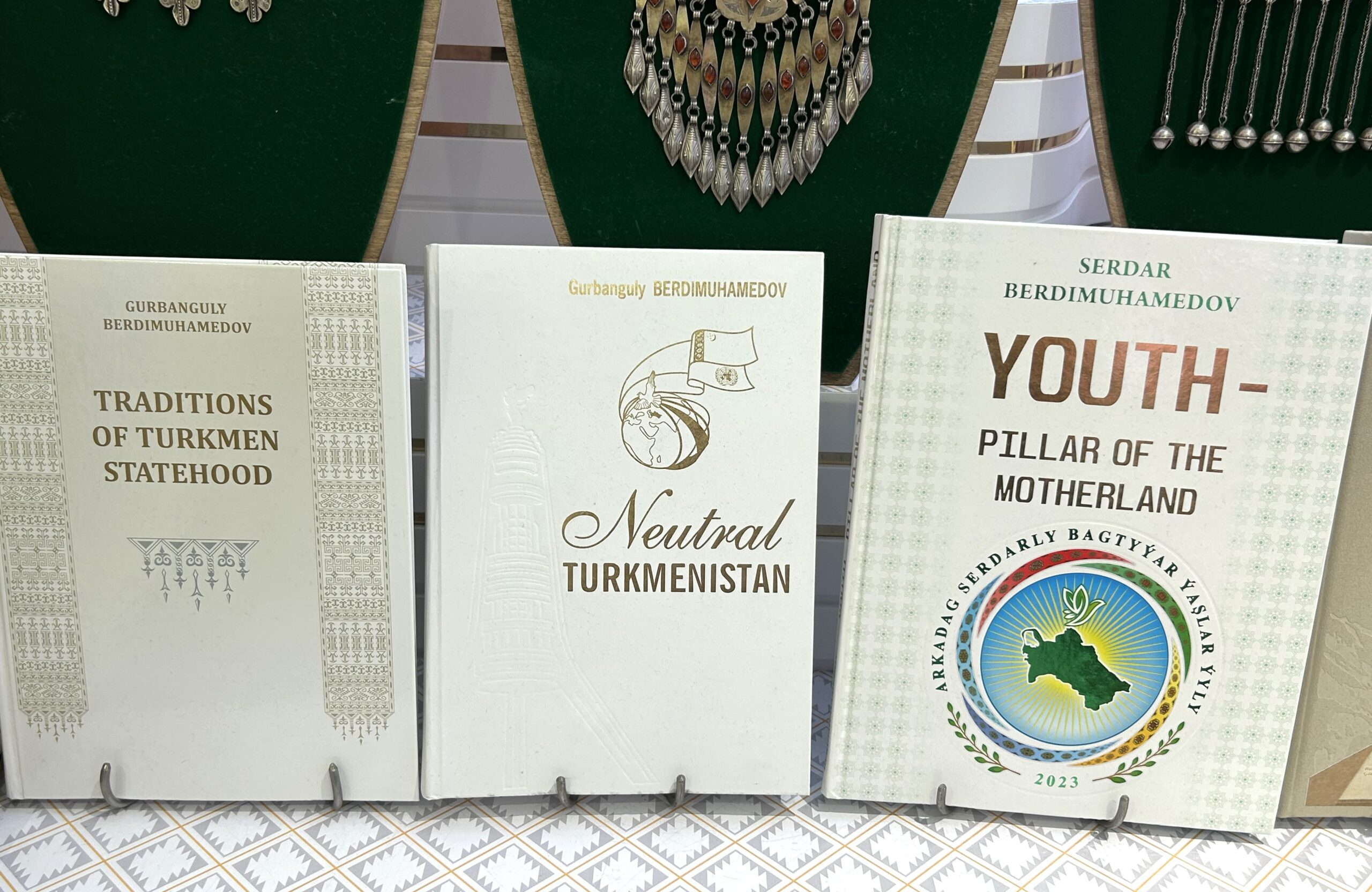

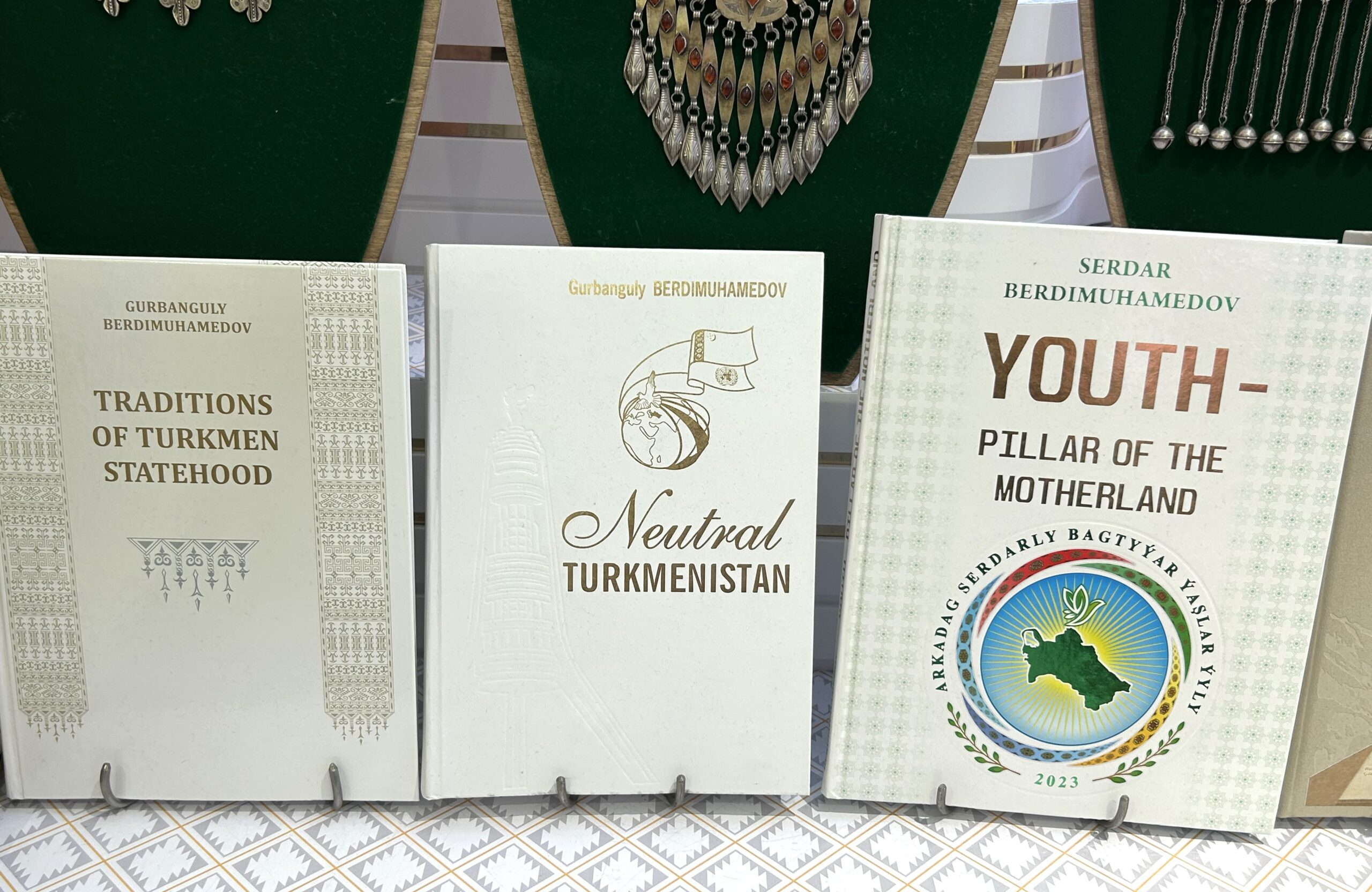

Books on display in the Turkmenistan Pavilion at the Osaka Expo 2025; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov is now Chairman of the Halk Maslahaty, or People’s Council, having essentially handed over the presidency to his son, Serdar, in March 2022. Both will host an event dedicated to the 30th anniversary of the UN’s official recognition of Turkmenistan’s permanent neutrality, and Serdar has managed to publish his latest book, Turkmenistan’s Neutrality: A Bright Path to Peace and Trust, just ahead of the commemoration. Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian is confirmed to attend. Russian President Vladimir Putin is scheduled to be in Ashgabat. The other four Central Asian presidents are expected to be there also. Other leaders might be on hand.

It is a grand celebration to mark something that happened in the course of a few minutes 30 years ago, but it has taken on a significance for Turkmenistan that no one could have predicted on December 12, 1995.