How a Kazakh Writer`s Book About American Couch Grass Was Written

During his lifetime, Gabit Musirepov was celebrated as a people’s writer, translator, dramatist, critic, academician, Hero of Socialist Labor, and statesman. Known in Kazakhstan as the “Master of Words,” he became a figure of national pride, and his works continue to be widely read today.

What is less known, however, is the story of his very first book. Long before he became famous for his fiction, Musirepov published a small agricultural manual titled Amirkan Bidayygy (American Couch Grass). Released in 1928 by the “Kazakhstan State” publishing house in Kyzylorda with a circulation of 5,000, the booklet sought to answer a pressing question: how could Kazakh farmers improve their fields and livestock fodder?

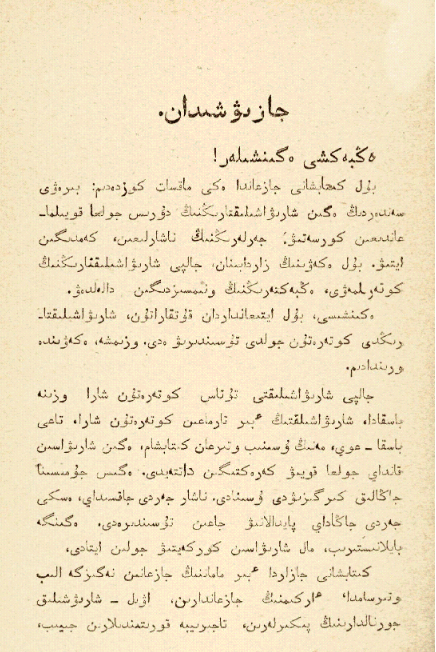

First page of book Amirkan Bidayygy (American Couch Grass)

The introduction explained the need for such a work. At the time, Kazakh peasants planted oats, millet, wheat, and barley, but often without proper techniques. Fodder crops were largely unknown, except in limited areas along the Syr Darya River. Previous manuals existed, but they were poorly translated from Russian or intended for experienced Russian farmers, making them inaccessible to Kazakhs. Musirepov’s book, written in plain language and tailored to local conditions, filled that gap.

This was Musirepov’s first published book. He wrote it in early 1927, the same year his first prose work, In the Grip of the Sea, appeared later in the autumn. Fellow writer Sabit Mukanov recalled: “After graduating from the Orenburg Workers’ Faculty in 1926, Gabit entered the Agricultural Academy in Omsk. In early 1927, he sent me his booklet Amirkan Bidayygy for publication. We printed it. I still keep his letter where he wrote, ‘The money from this book kept my family fed for half the winter.’”

The publisher acknowledged in the foreword that the young author might have overlooked some scientific details, but praised the work as “one of the best guides for improving the lives of Kazakh peasants,” insisting that every farmer should read it.

Musirepov`s introduction

In his own introduction, Musirepov explained, “I had two goals. First, to show why farming remained unproductive by pointing out poor land conditions. Second, to offer ways of overcoming these problems and raising productivity. I believe I achieved both.”

This statement reflects the sincerity and social purpose that would later define his literary career: whatever he wrote, it was always with the hope of benefiting his people.

Musirepov also asked a practical question: What kind of grass does the Kazakh land need? His answer was clear – crops that could withstand severe winters, scorching summers, and drought, while producing abundant, nutritious fodder and enriching the soil. After considering various options, he concluded that yellow alfalfa and American couch grass were the most suitable. Of the two, he argued, couch grass was best suited to Kazakhstan’s harsh climate.