Rail, Water, and Helicopters – Uzbekistan’s “Limited Recognition” of the Taliban

Uzbekistan has spent the middle of September embroiled in an increasingly tetchy press battle over an unusual topic: helicopters. The Taliban, who run the de facto government in Kabul, have long claimed that several dozen military aircraft and helicopters currently residing in Uzbekistan are rightfully theirs.

On September 11, a Taliban official announced publicly that Uzbekistan had agreed to hand them back. This was reported widely in the regional media, with the Uzbek foreign ministry slow off the mark in denying these claims.

The dispute goes back to the fall of Kabul in August 2021, when a total of 57 aircraft were flown from Afghanistan to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan as Ashraf Ghani’s government collapsed.

“The helicopters came from the Afghan territory to Uzbek territory illegally, so actually we had the right to confiscate them,” Islomkhon Gafarov, an Afghanistan expert at the Center for Progressive Reform, a Tashkent think tank, told the Times of Central Asia.

However, Gafarov adds that the aircraft were the property of the U.S. military loaned to the previous government of Afghanistan, and therefore, Washington will have a say in their return.

This has not stopped the Taliban from continuing to demand the helicopters back for use in “humanitarian operations,” in the words of Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi.

Such wrangling is part of the daily diplomatic in-tray for Tashkent when dealing with a neighbor whose government has not been recognized by almost the entire world.

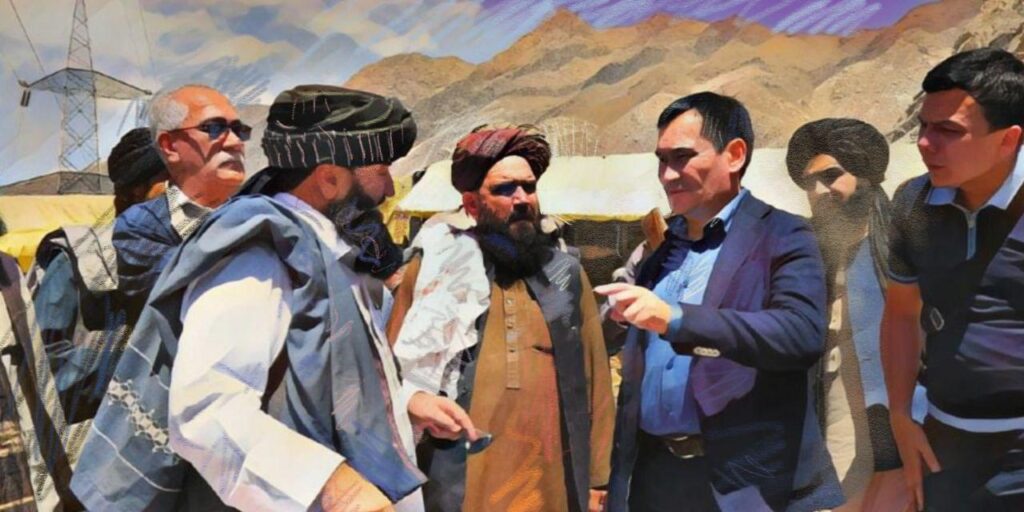

“Afghanistan is our neighbor,” said Gafarov. “According to the geopolitical situation, we have to conduct a dialogue with this government. It’s true, Uzbekistan hasn’t recognized the Taliban government, but de facto, we work with them; we’ve had diplomatic relations with them since 2018.”

Tashkent certainly has reasons to work with the Taliban. Helicopters are a mere sideshow compared to two far larger issues that will define their relations for years to come: rail and water.

Railway

On the positive side of the ledger, the Taliban have brought to Afghanistan a reasonable degree of stability – enough to start contemplating large-scale infrastructure projects. In July, an agreement was struck between Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan to conduct a feasibility study for a trans-Afghanistan railway, with 647 kilometers of new track being laid to link Uzbekistan with Pakistan’s Indian Ocean ports.

This railway could bring significant benefits to Uzbekistan, one of only two double-landlocked countries in the world. Currently, sea-bound exports must travel via Turkmenistan to Iran. Other routes almost all rely on going via Kazakhstan. The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, currently being constructed, should remove some of the need for sea-bound routes, but the Pakistan route would be faster.

“The trans-Afghan route is the shortest way to the seaports of Karachi and Gwadar,” Gafarov told TCA. With a line from Termez, Uzbekistan, to Mazar-i-Sharif in Northern Afghanistan already operational, this only leaves two sections unbuilt – from Mazar to Kabul, and then from Kabul to Peshawar in Pakistan.

The teams are still only at the feasibility stage right now, and have, with some chutzpah, predicted that it will be completed in just five years. But the project is filled with assumptions that many argue are unrealistic. Afghanistan has some of the world’s most challenging terrain, as well as an unpredictable security situation.

“Another problem is the difficulties between Afghanistan and Pakistan,” Gafarov said. “There have been several conflicts across the Durand Line since the end of last year.” Pakistan has accused Afghanistan of providing aid and shelter to the Tehrik-e-Taliban, or Pakistani Taliban, which has led to conflict in border areas and strained relations between the two states. A raid on Tehrik-e-Taliban positions by Pakistani forces on September 12 led to 47 deaths.

This has also led to a gloomy prognosis in Tashkent. “Even if we build a railroad from Mazar-i-Sharif to Kabul, it’s the question of how we can build from Kabul to Peshawar,” said Gafarov. He adds that in his opinion, it might be worth Uzbekistan’s while putting more resources into accessing the sea via Iran’s Chabahar free port, which has been exempt from U.S. sanctions since 2018.

Water

Another issue forcing Tashkent to engage with the Taliban is water.

In March 2022, the Taliban began construction on the long-planned Qosh Tepa Canal, almost fifty years after the idea was first floated in 1973 by Afghanistan’s first President, Mohammad Daud.

The 285-kilometer-long canal is designed to divert 10 billion cubic meters of water from the Amu Darya to irrigate arid areas of northern Afghanistan. Construction has been progressing rapidly, with “Phase 2” of the project now 93% complete, according to an August update from the country’s National Development Corporation.

For Afghanistan, where some 12.6 million people face high levels of acute food insecurity, the project is a potential lifeline. But it will also siphon water from the Amu Darya, a river critical to Central Asia. Kabul insists it has the right to use the water. Afghanistan is not a party to the 1992 UN Water Convention and was also left out of the Almaty Accord, which sought to regulate the shared water resources in Central Asia following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Afghanistan also argues that it uses a minimal percentage of the water from the river compared to its neighbors.

Even so, the impact on Uzbekistan could be severe. The country depends heavily on the Amu Darya to irrigate its agriculture, particularly its thirsty cotton crop. Rising temperatures do not help as they increase evaporation. This year, Uzbekistan recorded its hottest June ever, with temperatures in the capital, Tashkent, hitting 43.5 degrees. On top of this is the issue of a growing economy and rapidly expanding population.

Uzbekistan already knows all too well how desertification can impact the country. The Aral Sea disaster remains a stark reminder of how water mismanagement can devastate health, livelihoods, and ecosystems.

There are also worries that Afghanistan, which has insisted on completing the canal without outside funding and expertise, may bungle parts of the project, leading to even greater water losses than expected. A breach in one of the outer dikes in 2023 compounded these fears.

However, in May 2025, there were steps in a more harmonious direction when Uzbekistan’s Deputy Minister of Agriculture, Jamshid Abduzukhurov, signed a bilateral agreement with the governor of Balkh Province in Northern Afghanistan on the joint management of the Amu Darya River.

“Theoretically, we call it the policy of limited recognition,” said Gafarov. “We don’t recognize the Taliban government yet, but on a regional level or sectoral level, we can recognize and deal with one another.”

Regional Solutions

Whether such agreements will withstand being buffeted by less benign geopolitical winds remains to be seen. As a region, Central Asia is beginning to wake up to the shared perils and opportunities of dealing with their southern neighbor, and is beginning to look beyond mere regional agreements. Late August saw the formation of the contact group on Afghanistan between all five Central Asian states.

Designed to present regional solutions and projects when dealing with Kabul, if it can be properly institutionalized, it may be another sign that Central Asian leaders are learning to find strength through unity as they mature as sovereign actors.