The year 2025 will likely be remembered as a milestone in Central Asian diplomacy. Regional leaders signed landmark agreements on water and energy cooperation and launched major investment projects. At high-level meetings, Central Asian presidents emphasized a new phase of deeper cooperation and greater unity, highlighting strategic partnership and shared development goals.

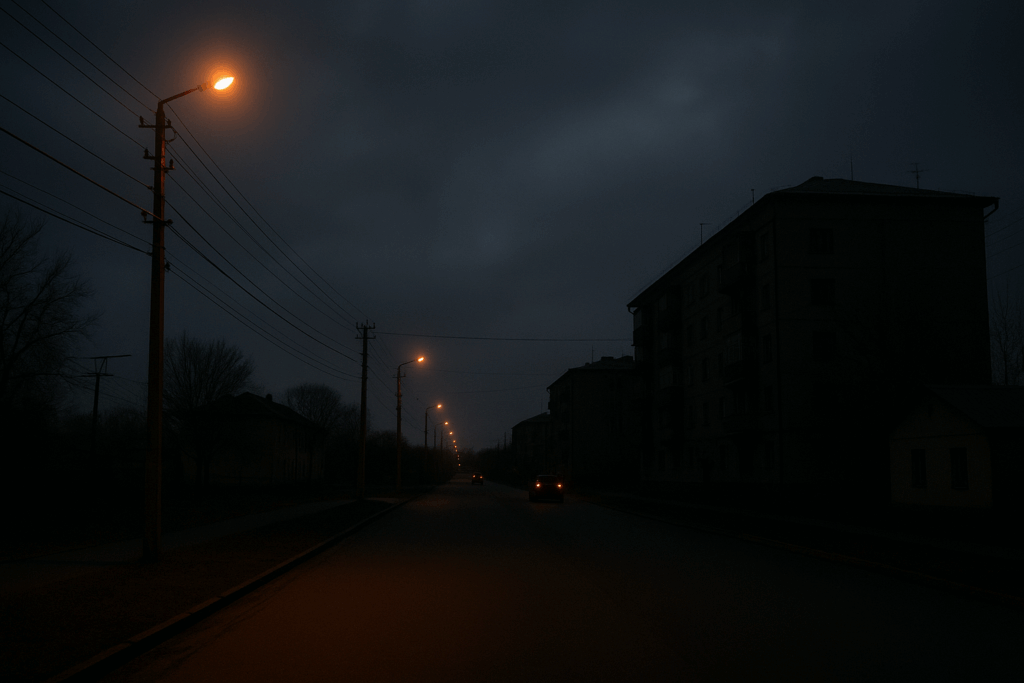

But at ground level, at border crossings such as Korday between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, or the congested diversion routes replacing the closed Zhibek Zholy checkpoint, the picture is far less seamless. Long queues, heightened scrutiny, and bureaucratic delays remain the norm.

While political rhetoric celebrates unity, the reality on the ground tells a different story. The region’s physical borders remain tightly controlled. A key symbol of unrealized integration is the stalled “Silk Visa” project, a proposed Central Asian version of the Schengen visa that would allow tourists to travel freely across the region. The project has made little headway, with experts suggesting that, beyond technical issues, deeper concerns, including economic disparities and security sensitivities, have played a role.

Silk Visa: A Stalled Vision

Launched in 2018 by Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, the Silk Visa was envisioned as a game-changer for regional tourism and mobility. Under the scheme, tourists with a visa to one participating country could move freely across Central Asia, from Almaty to Samarkand and Bishkek.

Seven years on, the project has yet to materialize. Official explanations point to the difficulty of integrating databases on “undesirable persons.” But as Uzbekistan’s Deputy Prime Minister acknowledged earlier this year, the delay stems from the need to harmonize security services and create a unified system. Experts also cite diverging visa policies and resistance from national security agencies unwilling to share sensitive data. As long as each country insists on determining independently whom to admit or blacklist, the Silk Visa will remain more aspiration than policy.

Economic Imbalance: The Silent Barrier

The most significant, albeit rarely acknowledged, hurdle to regional openness is economic inequality. Kazakhstan’s GDP per capita, at over $14,000, is significantly higher than that of Uzbekistan or Kyrgyzstan, which hover around $2,500-3,000. This disparity feeds fears in Astana that full border liberalization would trigger a wave of low-skilled labor migration, putting strain on Kazakhstan’s urban infrastructure and labor market.

While Kazakhstan is eager to export goods, services, and capital across Central Asia, it remains reluctant to import unemployment or social tension. Migration pressure is already high: according to Uzbekistan’s Migration Agency, the number of Uzbek workers in Kazakhstan reached 322,700 in early 2025. Removing border controls entirely could exacerbate this trend, overwhelming already stretched public services.

Security Concerns and Regional Tensions

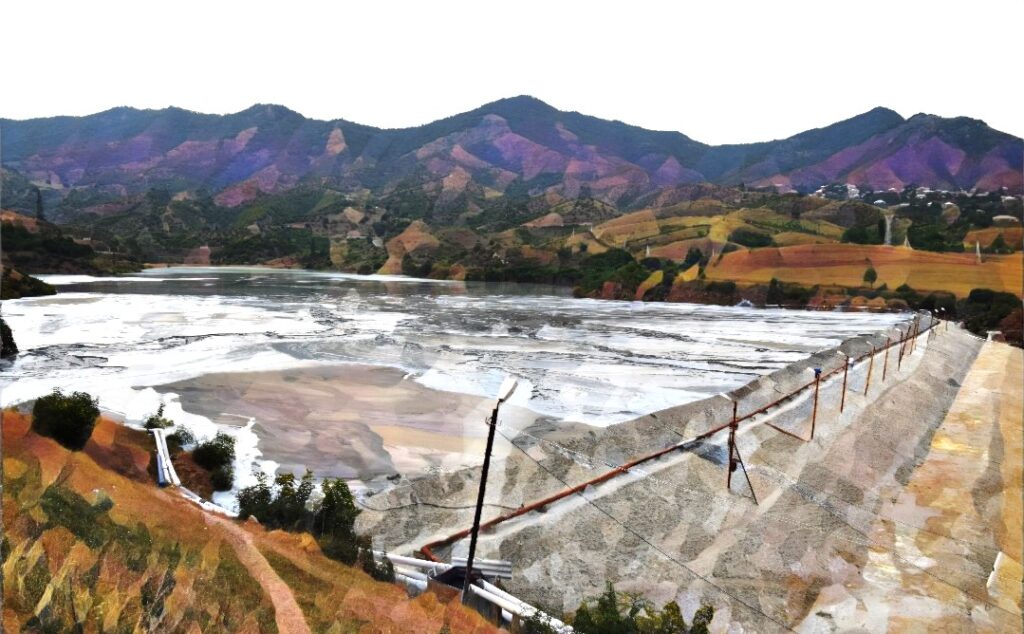

The geopolitical landscape further complicates the dream of borderless travel. A truly open regional system would require a strong, unified external border, something unattainable given Afghanistan’s proximity.

The persistent threats of drug trafficking and extremist infiltration compel Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to maintain tight border controls. Kazakhstan, while geographically removed, remains cautious about loosening controls along its southern frontier. Moreover, despite recent agreements on delimiting the Kyrgyz–Tajik border, tensions in the area remain unresolved, underscoring the fragility of regional trust, making the creation of a unified security space across all five countries a distant prospect.

The war in Ukraine has further complicated the region’s geopolitical calculus. Russia remains Central Asia’s primary destination for its migrant labor, but the conflict has strained Moscow’s economic capacity and pushed regional governments to diversify partnerships. This uncertainty reinforces risk-averse security policies, making leaders even less willing to consider fully open borders.

Reality Check: Trade Over Tourism

Perhaps the most tangible measure of regional integration is logistics. Yet even this is underwhelming. The Korday (Ak Zhol) crossing remains a choke point for trade between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Despite digital queueing systems, businesses continue to report delays, and truck drivers face multi-day traffic jams. These recurring trade bottlenecks indicate that borders are still used as tools of economic leverage, undermining promises of seamless transit.

Considering all factors, the emergence of a full-fledged ‘Central Asian Schengen’ in the foreseeable future appears unlikely. The combination of security risks and economic imbalance makes open borders politically unpalatable. Instead, the region may follow a model akin to “Two-speed Europe,” with elite-driven economic integration, such as simplified cargo transit and digital customs systems, advancing faster than broader public mobility. For most citizens, however, the dream of borderless Central Asia will remain just that: a dream.