Is it possible to preserve architectural heritage while working towards sustainability? And what to make of the architectural relics of the past century? Can they somehow take on new meaning rather than remaining a representation of dystopias and utopias of the past?

All these questions and more are addressed by the Uzbekistan Pavilion at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale. Running alternate years with the Art Biennale, this is undoubtedly one of the most important architectural events in the international arena.

Promising to be a thought-provoking exploration of Soviet-era scientific ambition, modernist architectural heritage, and the challenges of sustainability in a rapidly changing world, the pavilion hosts the research of GRACE studio – an architectural firm established by Ekaterina Golovatyuk and Giacomo Cantoni – which operates at the intersection of built heritage, contemporary urbanism, and cultural production.

Commissioned by the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF), the pavilion responds to the theme of the Biennale’s curator, Carlo Ratti’s overarching Biennale concept of ‘Intelligens‘.

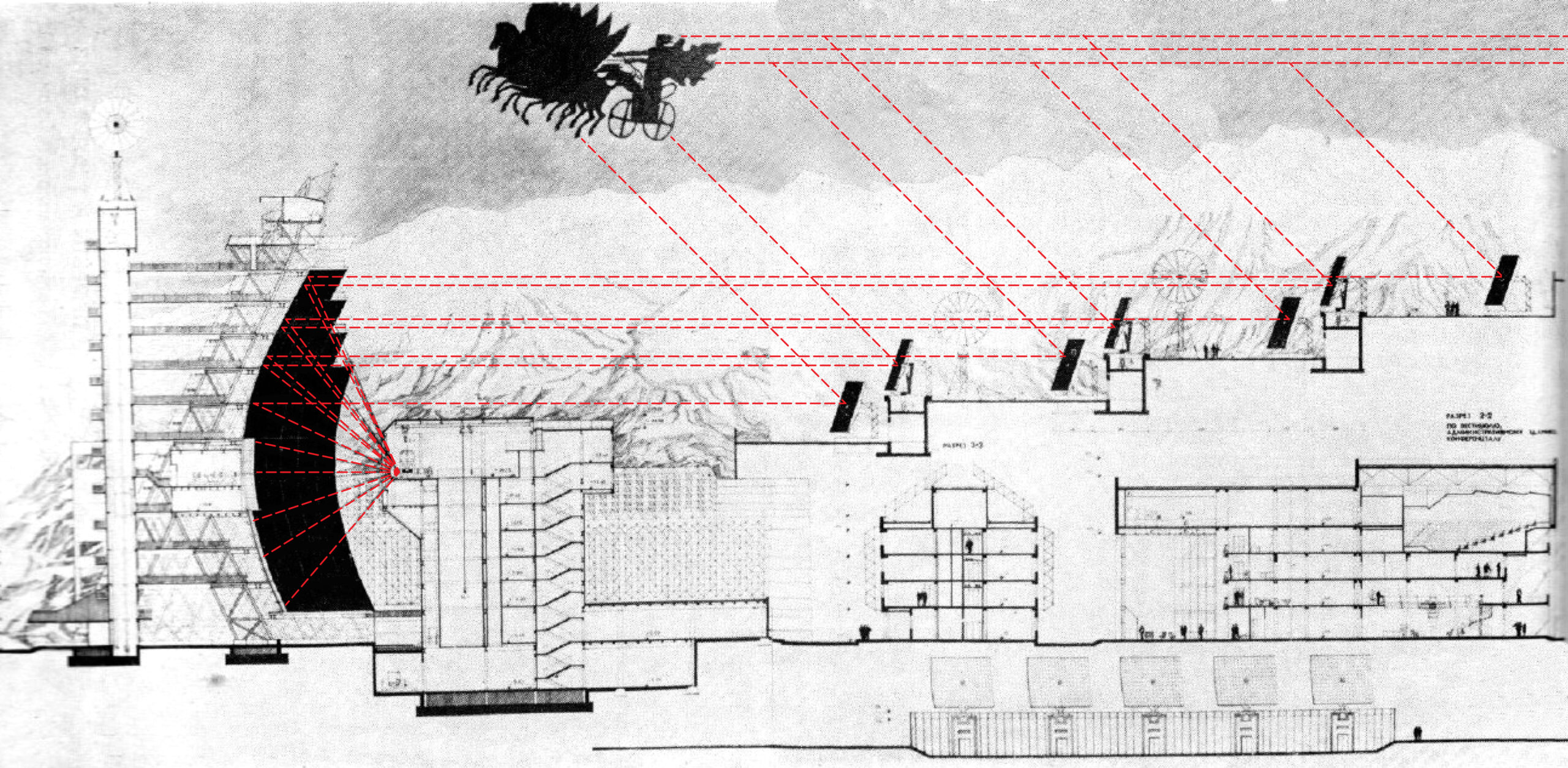

The pavilion focuses on the Sun Institute of Material Science, originally known as the Sun Heliocomplex, a vast Soviet-era solar furnace built outside Tashkent during the Cold War to test materials at high temperatures. What emerges is the paradox of a structure designed for technological advancement that now faces questions of obsolescence and adaptation in contemporary discourse.

TCA spoke with Ekaterina Golovatyuk to understand how the pavilion evolved from years of research into Tashkent’s modernist legacy and why this solar furnace has become the focal point of Uzbekistan’s presence at the Biennale.

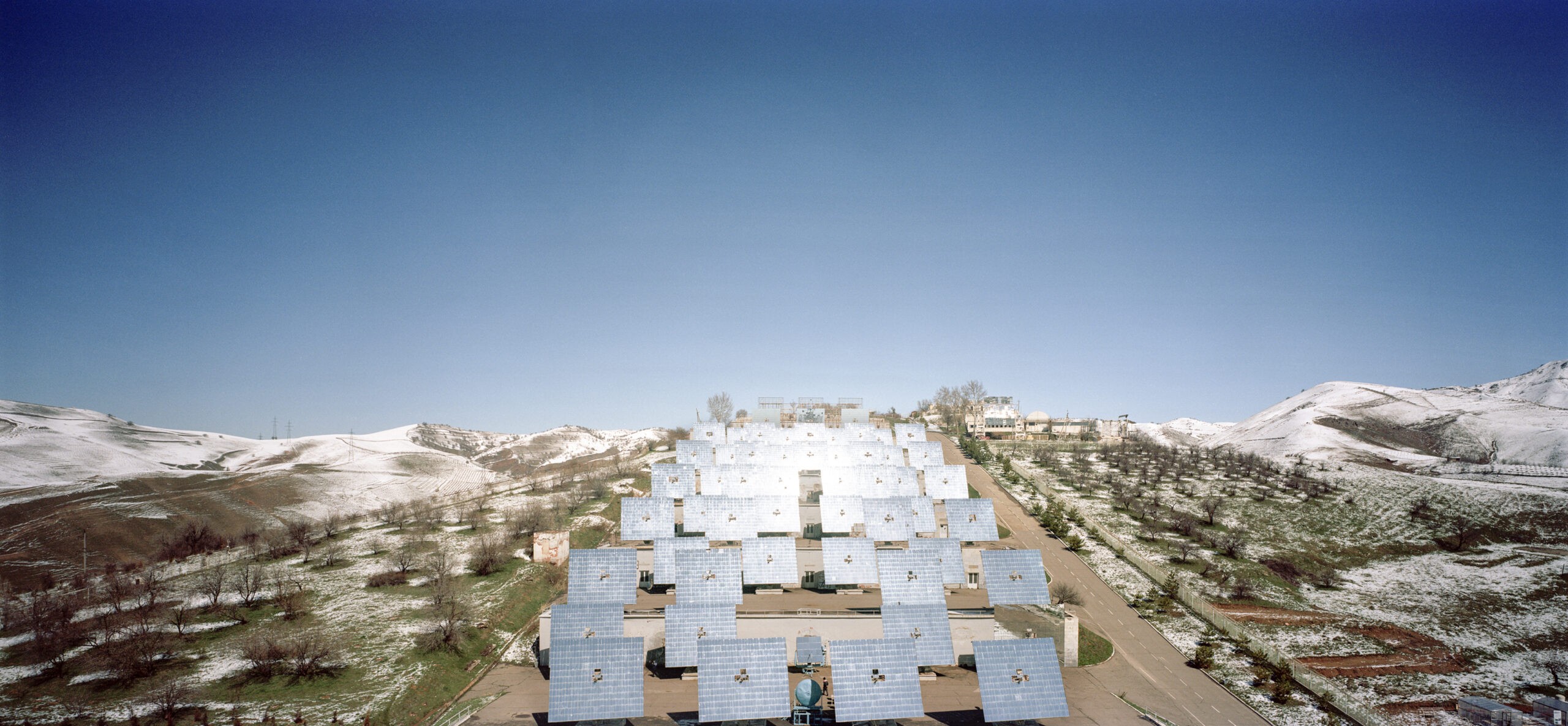

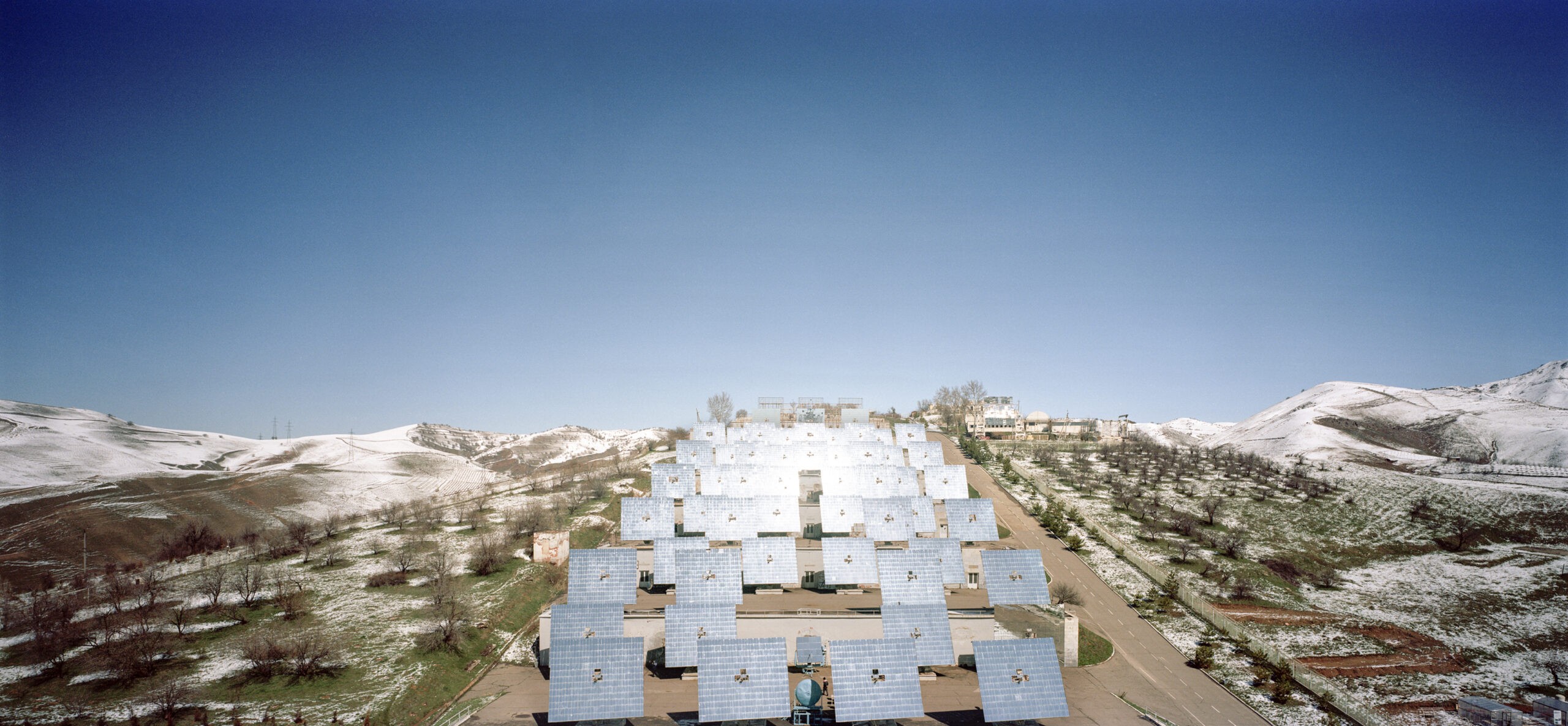

Heliocomplex Sun, field of heliostats, Tashkent, Uzbekistan; image: Armin Linke

TCA: The Uzbekistan Pavilion for the 2025 Venice Biennale builds on your previous research, Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI. Can you tell us how this project began?

This is a project commissioned and initiated by Gayane Umerova of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation that works with cultural heritage, museums, and other culture-related initiatives in Uzbekistan but also promotes Uzbekistan’s culture abroad. They have curated large exhibitions in the Louvre, in the British Museum, showing historical artifacts from Uzbekistan, but also art of the 20th century, and Tashkent Modernism is part of their mission in regards to architecture.

The Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI project began in 2021, when it became clear that Tashkent had started to change so rapidly that special tools had to be put in place in order to protect the recent architectural heritage that, at the time, was mostly not listed and therefore at risk. Our project team consisted of multiple experts from Uzbekistan and abroad, including a historian, Boris Chukhovich, a team of preservation specialists from Politecnico di Milano led by Davide Del Curto, urbanists Laboratorio Permanente, and an artist [photographer], Armin Linke.

For this project, we started by selecting 40 buildings and then narrowed it down to 24, for which we created monographs and statements of significance that described the important values of the building as well as what parts should be absolutely kept and what parts could eventually be transformed and adapted. An important message of our project was that given the diversity of Tashkent’s architecture and the different states of its preservation, our approach was very nuanced and specific for each building, providing a repertoire of solutions that ranged from almost doing nothing to restoration or adaptation.

View towards the concentrator and solar furnace, 1986. From the private archive of the Azimov family

TCA: How did the focus on the Sun Institute of Material Science emerge as the central theme for the pavilion?

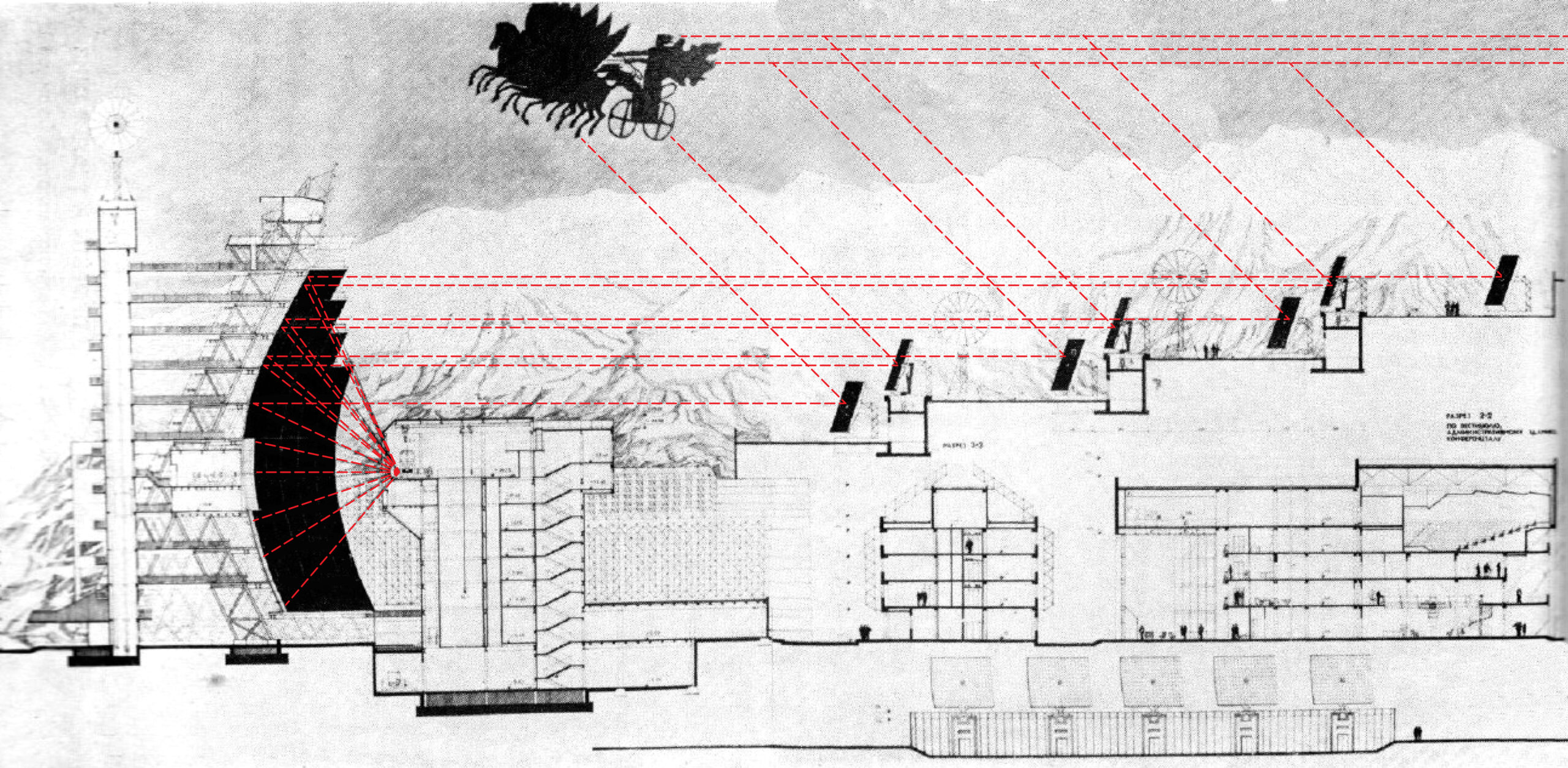

This complex emerged as the central theme because of all modernist buildings in our research, it was the one that responded to sustainability and the circularity manifesto proposed by Biennale’s curator Carlo Ratti. The Institute’s big solar furnace uses pure solar energy to heat materials to very high temperatures, nearly 3,000 degrees Celsius. We found this scientific infrastructure quite exceptional in terms of its technology, architectural scale, and quite peculiar functional ambiguity.

TCA: What was the original function of the solar furnace, and how did it change after 1991?

The project was born during the Cold War. France built the first prototype of such a furnace in the late sixties, and the Soviet one followed in 1987. The furnace was initially conceived as a tool to test materials at very high temperatures or to synthesize new materials.

After construction, the furnace was used mainly for the space and defense industries. When the Soviet Union fell apart, the complex lost many of its commissions. The furnace’s scale reflects the level of ambition of a large country such as the Soviet Union, and then it ended up being used in Uzbekistan, which is, of course, a much smaller country with different resources. It received basic funding for maintenance but could not function at full scale. The scientists tried to find applications in local industries and the agricultural sector, but the furnace was still, in a way, too big for any local tasks.

Section of the helisostatic field and the Process tower; Source: Architecture of USSR, n. 3-4, 1988

TCA: How does the pavilion address the history and paradoxes of this building?

The Pavilion’s narration departs from the point that the combination of massive scale that was part of its original idea and the historic events the entire region went through in the 1990s led to the fact that the scientists who ran this furnace had to continually reinvent new applications for it, because the original scope disappeared after just a few years.

So, the pavilion suggests that the large scale generates a kind of indeterminacy of use that is, in a way, a burden but also a guarantee of its possibility to adapt to shifting necessities of science or production. The pavilion narrates this ambiguity through fragments either reconstructed or brought from Parkent.

TCA: How does the pavilion fit into the overarching theme of the 2025 Venice Biennale, ‘Intelligens,’ curated by Carlo Ratti?

Among all the 24 modernist buildings we focused on during the Tashkent Modernism XX/XXI research project, we chose the big solar furnace precisely because it addresses the use of solar energy and is the best fit to help pose critical questions on sustainability. We don’t try to claim that the building is very sustainable, but we try to provide a more critical picture and a broader reading of what can be considered sustainable when you deal with a historic artefact.

All objects from the exhibition in Venice will travel to Uzbekistan in November 2025 and will continue to be used at the ‘Sun’ Institute.

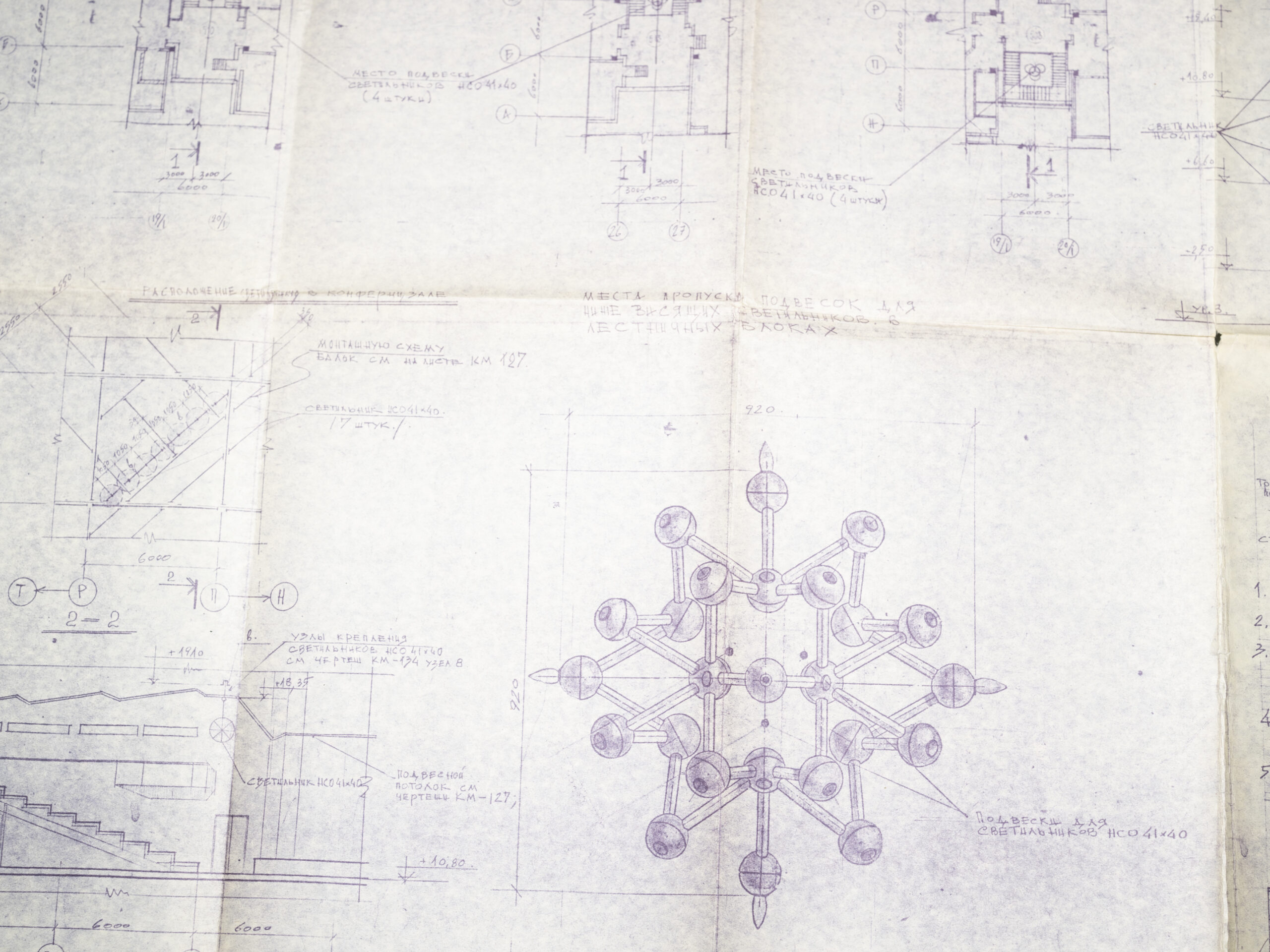

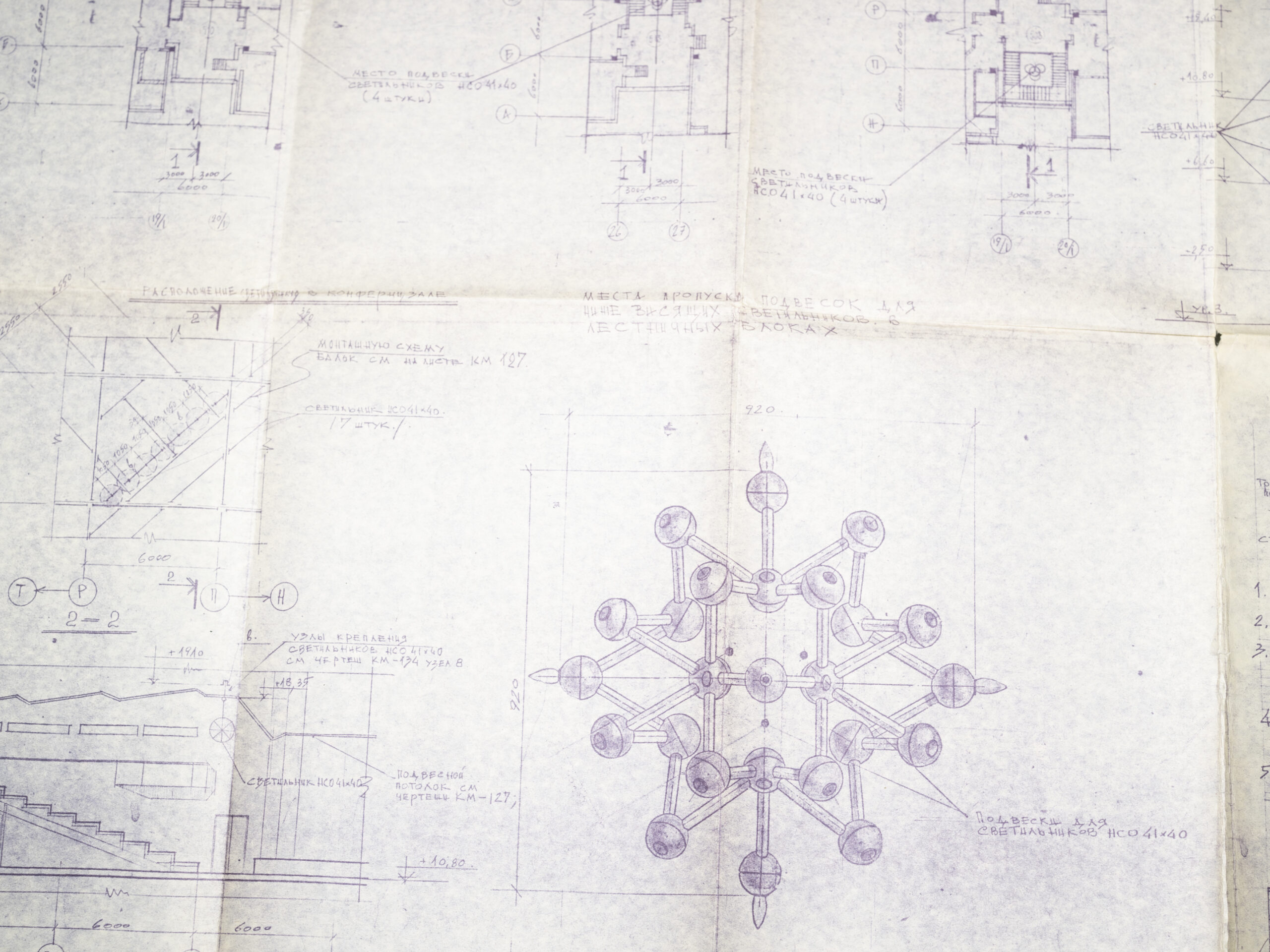

Heliocomplex Sun, lighting design, detail, Parkent, Uzbekistan; image: Armin Linke

TCA: You’re integrating artistic interpretations alongside scientific research; can you tell us more about this approach?

Already, the ‘Sun’ institute itself is an interesting hybrid of science, architecture, and art. The building has many beautiful works of monumental art that were part of the original project, so in the pavilion, we wanted to disclose the interdisciplinary nature of the complex by inviting different figures, from writers and artists to a theatre group from Tashkent, to engage with the furnace through their imaginations and different media.

TCA: What do you hope visitors will take away from the Uzbekistan pavilion?

Through this pavilion, we hope to inspire deeper discussions about how heritage and technology coexist in our changing world. Can you think of technology in terms of preservation? Is the latent role of this complex to formulate complex questions about science and technology? Is the large scale the reason for or an impediment to its survival?

Ekaterina Golovatyuk; image: Grace

The 19th International Venice Architecture Biennale will be open from Saturday, 10 May, to Sunday, 23 November.