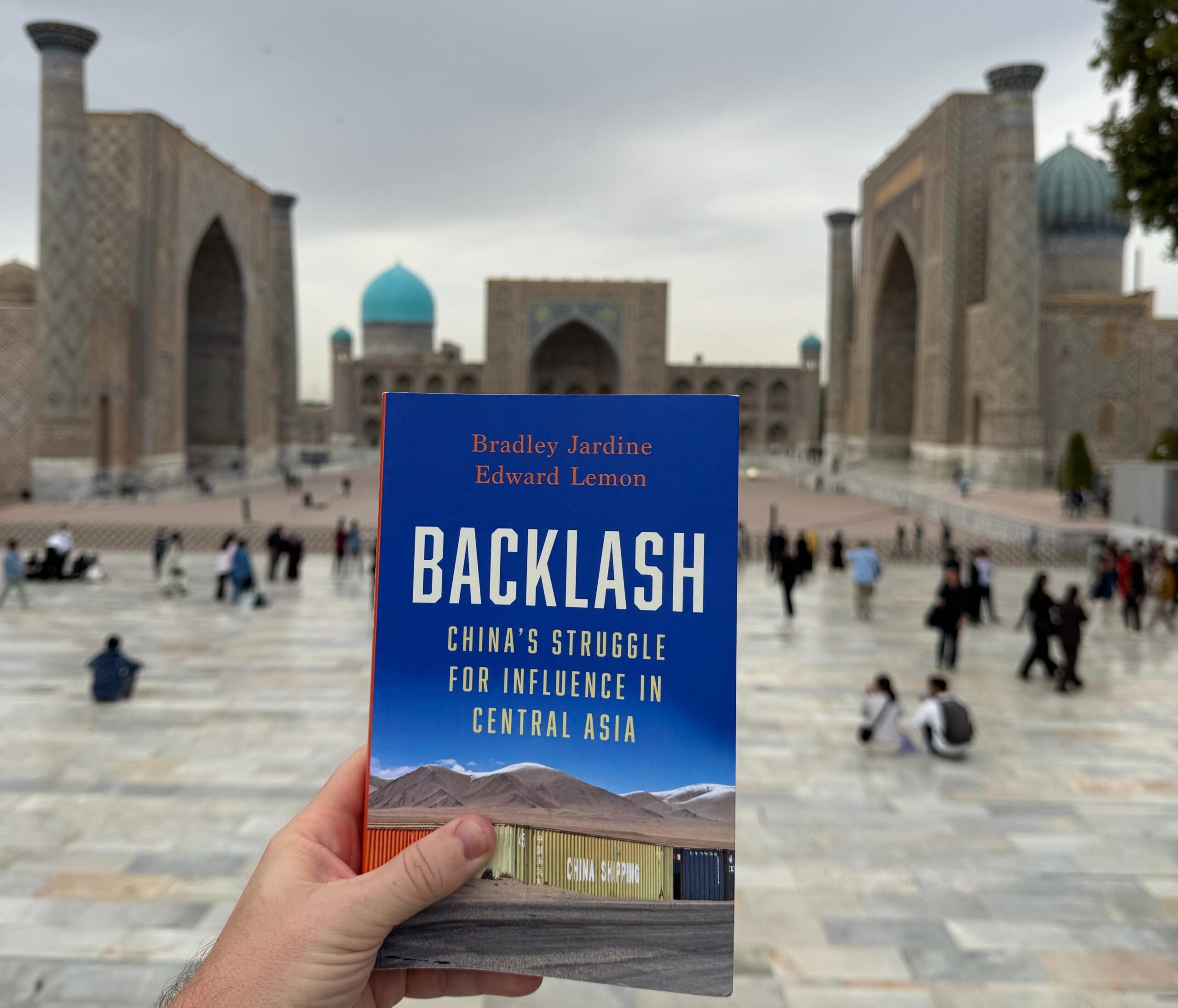

From Belt and Road to Backlash: Edward Lemon and Bradley Jardine Discuss China in Central Asia

As China invests billions in Central Asian oilfields, railways, and cities, the region’s response is anything but passive. In Backlash: China’s Struggle for Influence in Central Asia, Bradley Jardine and Edward Lemon document how Central Asians – from government halls to village streets – are responding to Beijing’s expanding footprint. The book provides a nuanced look at China’s engagement in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan over the three decades since these nations gained independence. Drawing on more than a decade of fieldwork, Jardine and Lemon ask a timely question: can Beijing maintain its growing influence in an environment where local voices and interests are increasingly assertive? The Times of Central Asia spoke with the authors.

TCA: Central Asia has become an increasingly strategic crossroads, rich in resources, young in demographics, and positioned between major powers. Yet China’s engagement appears far more ambitious than that of Western or regional players. In your view, what accounts for this asymmetry? Is it primarily a matter of geography and financial capacity, or has China been more politically and diplomatically attuned to Central Asia’s priorities than others?

J/L: China’s dominance in Central Asia stems from both geography and political attunement. As we note in Backlash, Beijing views the region as an extension of its own security frontier, as both a buffer protecting Xinjiang and a potential source of terrorism. It has built deep ties through consistent, elite-level engagement since the 1990s. Its approach blends vast financial capacity with political instincts that resonate with local elites: prioritizing sovereignty, stability, and non-interference rather than the governance conditionalities that often accompany Western aid and investment. Through the Belt and Road Initiative, which was launched in the region in 2013, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which was established in 2001 with four Central Asian republics as founding members, and newer platforms like the China-Central Asia (C+C5) summit, China offers infrastructure, energy investment, and regime security in ways tailored to the needs of authoritarian partners. Unlike the episodic or values-driven engagement of Western actors, and with Russia’s attention increasingly divided, China’s steady, pragmatic diplomacy, backed by proximity and resources, has allowed it to entrench itself as the region’s indispensable power.

TCA: China’s expanding presence across trade, infrastructure, and finance has reshaped Central Asia’s economic landscape. To what extent do these investments remain primarily commercial, and when do they start to carry political or strategic implications? How do local governments manage the risks of dependency or debt while pursuing development gains?

J/L: China’s expanding economic footprint in Central Asia may be driven by trade and infrastructure, but the lines between commerce and strategy have become increasingly blurred. As we note in Backlash, Beijing’s investments, roads, pipelines, railways, and energy grids are rarely purely commercial. They create structural dependencies that bind Central Asian economies to China’s markets, finance, and technology. By 2020, roughly 45% of Kyrgyzstan’s external debt and more than half of Tajikistan’s were owed to China, while around 75% of Turkmenistan’s exports flowed to Chinese buyers. These imbalances give Beijing quite a leverage, often translating into diplomatic support on sensitive issues like Xinjiang at the United Nations. Still, local governments are not passive: they manage these risks through diversification, courting Gulf, Western, and Turkish investment, and by invoking “multi-vector” foreign policies to balance great-power influence. At the same time, they have used Chinese support to help bolster their ability to rule distant areas like the Ferghana Valley and Tajikistan’s Pamir region. Yet opaque deals, elite capture, and public resentment over land use and labor practices mean that even as leaders seek development gains, they must constantly navigate the political backlash that accompanies China’s economic rise.

TCA: In Central Asia, public reactions to Chinese projects have at times been resistant, driven by concerns over transparency, sovereignty, and local impact. Yet overall attitudes toward China remain mixed and continue to evolve as governments balance public skepticism with the economic and strategic advantages of deeper engagement. How should we interpret these instances of protest or criticism within that broader context? Do these episodes of protest suggest a broader regional recalibration in attitudes toward China, or do they reflect more localized tensions that coexist with pragmatic cooperation?

J/L: Protest and criticism are best read as localized stress tests on a still-pragmatic relationship – not a wholesale regional turn away from China. The patterns we document show backlash clustering where projects provoke concerns over control of land, labor rights, or the environment (e.g., mines, refineries, logistics hubs), and in the two more protest-permissive states, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan; of 191 China-related protests since 2010, 92% occurred in those two countries, with incidents largely about land/leasing, extractives, and Xinjiang rather than abstract geopolitics.

Public opinion is mixed and fluid (captured by the Chinese saying “warm politics, cold publics”): skepticism spiked between 2019 and 2021, then eased somewhat by 2023 in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, even as Uzbekistan’s negative attitudes rose – evidence of heterogeneous, issue-tethered sentiment rather than a uniform anti-China turn. In parallel, governments keep balancing: they suppress flashpoints, bank the economic upside, and pursue multi-vector hedging rather than realignment. The upshot: protests signal where China’s model grates, transparency, sovereignty, local impact, while coexisting with elite-level cooperation; cumulatively, they pressure Beijing to adapt (localization, skills programs, softer messaging) and pressure host states to demand cleaner, more accountable deals, but they do not, on their own, amount to a region-wide rupture.

TCA: All five Central Asian states continue to pursue multi-vector diplomacy, engaging China alongside Russia, Western institutions, and emerging partners from the Gulf and South Asia. Yet results have been mixed: attracting substantial non-Chinese investment remains a persistent challenge. How sustainable is this balancing strategy in practice? Can it deliver real economic diversification, or will China’s financial scale and reliability ensure it remains the region’s dominant partner?

J/L: Multi-vectorism is sustainable as a tactic, but it delivers only partial diversification – China is likely to remain first among equals economically. The region has widened its dance card (C5+1, EU Global Gateway, Gulf money, Turkey’s rise, India’s outreach). Yet, structural realities keep tilting the floor toward Beijing: proximity and pipelines, the scale and speed of Chinese finance, entrenched trade in energy/minerals, and Beijing’s steady institution-building (SCO, C+C5) that converts commerce into influence. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have the greatest amount of agency and can peel off meaningful projects, especially in critical minerals, renewables, and manufacturing, and intra-regional “balancing regionalism” helps. But poorer, smaller economies (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan) remain debt- and import-dependent; Russia still dominates security and migration flows; and headline alternatives (e.g., the Middle Corridor) face cost/capacity bottlenecks. Ultimately, multi-vectorism buys bargaining power and niche diversification, not a wholesale rebalance: expect a mosaic where China provides the backbone of complex infrastructure and finance, the Gulf/Turkey adds sectoral capital, and the U.S./EU compete in select lanes (critical minerals, governance, tech) with the region’s room to maneuver shrinking when great-power pressures spike.

TCA: Russia’s war in Ukraine has tested Moscow’s influence in Central Asia and reshaped regional dynamics. How has this affected China’s approach? Has Beijing adjusted its strategy in response, and what lessons might it draw from Russia’s experience in managing regional relationships?

J/L: Beijing has treated the Ukraine war as both a warning and an opening. With Russia distracted and less bankable, China has tightened its “first-among-equals” role in Central Asia – elevating the C+C5 format that excludes Moscow, expanding security and surveillance cooperation, and casting its Global Security Initiative as the region’s stability framework – while still avoiding steps that would overtly trample Russian equities. You see this two-track in practice: Xi’s public pledges to uphold Kazakhstan’s sovereignty and territorial integrity (a pointed signal after Russian elites questioned Kazakh statehood), alongside a steady build-out of bilateral corridors, arms sales, training, and a small footprint in Tajikistan, all framed as counter-terrorism and regime security rather than sphere-of-influence politics. At the same time, Beijing has learned from Russia’s missteps: don’t over-militarize; do work through elites; translate commerce into influence via parallel institutions (SCO, then C+C5); and let geography and finance do the heaviest lifting. The result is adjustment, not rupture: China exploits the space created by Russia’s war (e.g., more re-exports and logistics work-arounds, higher-level summits without Russia), but it still calibrates to avoid a frontal challenge where Moscow retains leverage (transit routes, remittance ties, CSTO legacies). The lesson taken: patient, institutionalized, elite-centric statecraft beats coercive dominance, and Central Asia’s multi-vector hedging is a feature to be managed, not a problem to be crushed.

Backlash: China’s Struggle for Influence in Central Asia by Bradley Jardine and Edward Lemon is now available from all good retailers.