The explosive conflict between Iran and Israel, including coordinated U.S. strikes on Iranian nuclear infrastructure, has drawn global attention to the Persian Gulf and Levant. The escalatory spectacle, however, has blinded most observers to a quieter structural shift. This is the rising indispensability of Central Asia, including its linkages with the South Caucasus.

Unaligned in rhetoric and untouched by spillover, Central Asia’s very stability quietly threw into relief its increasing centrality to Eurasian energy and logistics calculations. As maritime chokepoints came into question and ideological rhetoric became more inflamed, Central Asia offers a reminder that the most valuable nodes in a network are the ones that continue operating silently and without disruption.

Neither Israel nor Iran has real operational depth in Central Asia, and this has made a difference. Unlike Lebanon, Iraq, or Yemen — where proxy networks or ideological leverage allowed Tehran to externalize confrontation — no such mechanisms exist east of the Caspian Sea. Iran’s efforts in Tajikistan, grounded in shared linguistic heritage and periodic religious diplomacy, today remain cultural and informational rather than sectarian and clientelist.

The influence of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in Central Asia is minimal; Israeli presence, while diplomatically steady in places like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, is neither controversial nor militarized. There are no significant arms flows or dual-use infrastructure for either side to use. As a result, Central Asia has remained untouched by the conflict.

Although the Iran–Israel conflict is relatively geographically localized, it has shed light on global systems far beyond the immediate zone of combat. Although not so far from the missile trajectories and nuclear facilities, Central Asia and the South Caucasus are remarkably insulated from their effects. Rather than becoming another theater of contestation, they have demonstrated their value as stabilizing elements at a time of heightened geostrategic volatility.

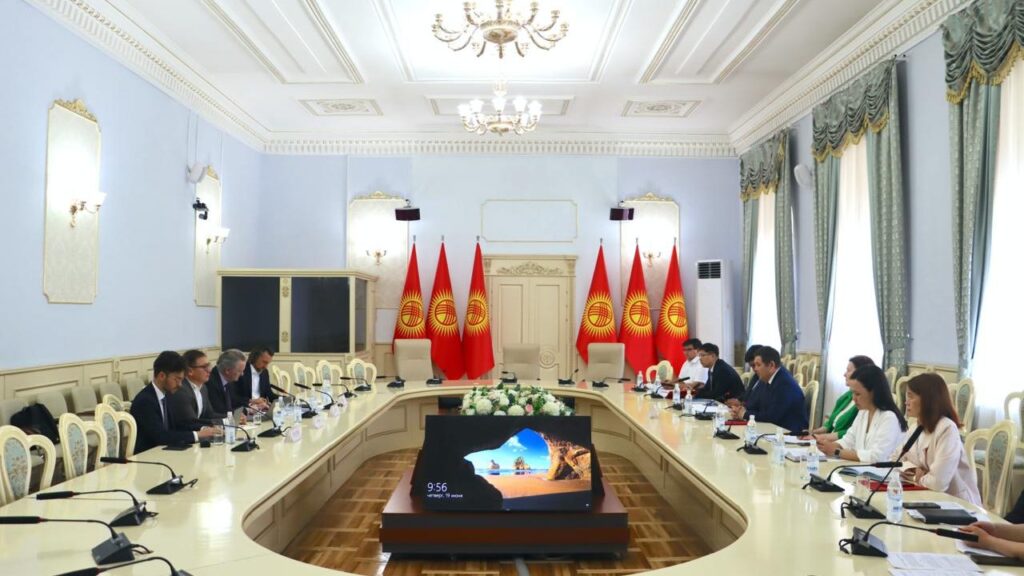

It is no longer optional to take into account the Central Asian space, which geoeconomically includes Azerbaijan, now a permanent fixture at the region’s summits. As the war now produces a phase of reactive adaptation in international geoeconomics and diplomacy, the region has become a control parameter of the international system rather than a fluctuating variable dependent upon it.

The Iran–Israel conflict has drawn new attention to the vulnerability of maritime energy corridors, especially the Strait of Hormuz, through which a fifth of the world’s oil passes. While contingency planning has focused on naval logistics and airpower deterrents in the Gulf, the Eurasian interior has remained materially unaffected, reflecting its structural indispensability. Central Asia and the South Caucasus, particularly Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, offer existing and potential overland alternatives that bypass maritime chokepoints entirely.

Kazakhstan’s oil continues to flow via the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) pipeline to the Black Sea, while Azerbaijan’s infrastructure, anchored by the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) corridor, links Caspian energy to Mediterranean terminals. These routes are not replacements for Persian Gulf volumes, but, as redundancies, they acquire significance as stabilizing arteries as well as increased relevance in moments of system stress. The war has thus sharpened a fact already known in energy strategy circles: overland continuity through Central Asia and the Caspian and South Caucasus corridor is not about volume but about resilience.

The same logic extends beyond hydrocarbons. The Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian International Trade Route, TITR) has quietly increased its throughput volumes since Russia’s war in Ukraine disrupted northern routes. Even during the Iran–Israel conflict, freight has continued to move uninterrupted along these overland routes. Such continuity reflects years of quiet investment in rail modernization, customs harmonization, and port interconnectivity, which is still ongoing.

Central Asia’s insulation is not only material but also ideological. Unlike parts of the Middle East where the Iran–Israel conflict has triggered rhetorical mobilizations or proxy signaling, Central Asia has remained outside the ideological line of fire. The region’s majority Sunni population, shaped by Hanafi traditions and post-Soviet secularism, offers little traction for Tehran’s Shia revolutionary narrative. Even Tajikistan, despite a close ethno-linguistic relationship with Iran that is rooted in shared Persianate heritage and mutually intelligible languages, did not issue any public solidarity statement during the conflict; nor did Iranian religious diplomacy generate visible mobilization in the population.

Groups that have historically opposed regional governments (e.g., Hizb ut-Tahrir in Uzbekistan or the internationalized remnants of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan that spread throughout the region) are Salafi-oriented or nationalist in impulse, and likewise often antagonistic toward Iranian positions. Iran’s economic and religious diplomacy in both Tajikistan and Turkmenistan (the only Central Asia state with which it shares a border) has remained limited in scope and carefully managed by the governments in place.

This ideological distance is further attenuated by diplomatic caution. Central Asian states have developed pragmatic relations with both Israel and Iran, but have declined to take sides rhetorically. Kazakhstan has long engaged Israel in agricultural and technological cooperation, but it has maintained official silence during the war, as did Uzbekistan. Thus, no Central Asian state has become a platform for rhetorical escalation or even a venue for protest. This is so because Central Asian diplomacy has generally aligned itself with strategic neutrality in order to minimize visible entanglements, while hedging through multilateral and plurilateral institutions.

That restraint has not gone unnoticed internationally. The United States, while publicly less engaged in the region, has quietly increased diplomatic signaling and is seeking to become re-involved. The European Union, long concerned with energy diversification, has begun to treat Central Asia less as a buffer and more as a logistical and ideological hinge between East and West. China, already structurally embedded through the Belt and Road Initiative and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, views the region’s neutrality as essential to preserving overland connectivity.

Central Asia’s insulation from escalatory entanglement is no longer a product just of internal intent. That is because the external environment has now shifted so as to incorporate this systemic role of the region. The Central Asian countries have not changed their outward behavior, but the international system has adapted to them. The region is no longer marginal or drifting; rather, it is an active participant in conditioning its neighborhood. The facts of its logistical corridors, regulatory stabilities, and ideological neutrality are entering the strategic calculus of powers even outside its neighborhood. What was originally an initiative from within has been transformed into a structural demand from without.

In complex-systems terms, the international system has “recategorized” Central Asia. In practical strategic terms, this means that Central Asia now occupies a position of increased centrality, not because it has asserted power, but because its self-defined operational mode has become integral to the overall system’s optimal functioning. Likewise, its neutrality — as a corridor of last resort and buffer against ideological contagion — operates as ideational infrastructure providing global-architectural redundancy. The region has not declared a new role, but the system has conferred one. That transformation is structural, not declarative; and it is already in effect.