TASHKENT (TCA) — On his path to political and economic reforms, the new Uzbek president Mirziyoyev is facing many risks and challenges, and many of them are beyond his control which makes his task even more difficult. We are republishing this article on the issue, originally published by Stratfor:

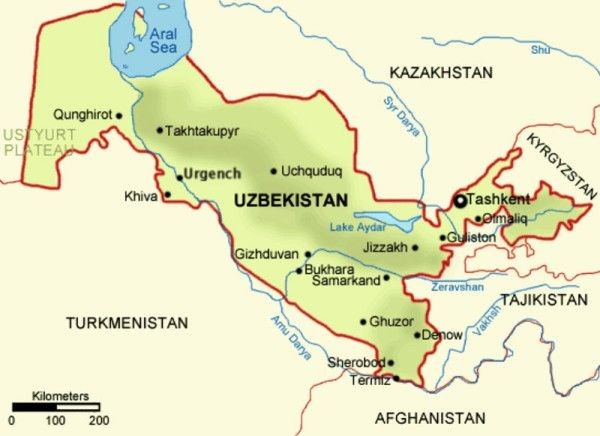

The countries of Central Asia are not known for rapid change or substantial reform, but Uzbekistan is experiencing both. Until his sudden death from a brain aneurism in 2016, Uzbekistan had been ruled through a centralized government headed by Islam Karimov, president since the country declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Under Karimov, Uzbekistan was highly isolationist, eschewing strategic alignments with foreign powers and engaging in bitter disputes with its Central Asian neighbors over border demarcation and water rights. A pervasive security apparatus controlled the country domestically, while the economic and monetary systems were tightly regulated and largely closed to foreign investment.

Karimov’s death triggered a long-planned and well-orchestrated transition of power to Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who had served as prime minister for 13 years before his ascension. Mirziyoyev took over as acting president Sept. 8, 2016, then formalized his role through a presidential election in December in which he garnered nearly 89 percent of the vote. Just over a year into Mirziyoyev’s rule, many Karimov-era policies have been modified in significant, yet complicated, ways.

Opening to Security Alliances

Upon taking office, Mirziyoyev pledged to maintain his predecessor’s strategic vision for Uzbek neutrality by staying out of foreign alliances, especially military ones. Although Uzbekistan did undergo periods of military cooperation with foreign powers under Karimov’s rule, including granting basing rights to the United States for its war in Afghanistan from 2001-2005 and accepting a temporary membership in Russia’s Collective Security Treaty Organization, he kept Uzbekistan an arm’s length from the region’s influential powers. However, the country has been more open to security cooperation with external powers, particularly Russia, under Mirziyoyev. Uzbekistan signed a military technical cooperation agreement with Russia in November 2016, and the two countries will hold their first bilateral military exercises in over a dozen years on Oct. 3-7.

A deteriorating security environment in Central Asia is driving Uzbekistan and Russia closer together. Low global energy prices have hampered the Uzbek economy, which largely depends on oil and natural gas exports. The country, which has faced significant problems with militancy, grapples with poor socio-economic conditions caused by low global energy prices and rapid population growth. Although it is unlikely to join the Collective Security Treaty Organization or Eurasian Economic Union, greater collaboration on military exercises and weapons sales is likely.

It’s also likely that Uzbekistan and its neighbors will draw closer. The border and water disputes fostered mistrust among Central Asian countries, but so did a series of poor personal relationships between Karimov and other Central Asian leaders. Mirziyoyev has distinguished himself from his predecessor by pursuing stronger ties with those countries. These efforts have borne fruit: Uzbekistan signed a deal with Tajikistan to restore air links in April, struck a landmark border demarcation and hydropower deal with Kyrgyzstan on Sept. 5, and agreed to a wide range of bilateral cooperation agreements with Kazakhstan on Sept. 17. Strain on resources — particularly water supplies — in the region will make cooperation with neighboring countries to manage these resources increasingly important for Uzbekistan.

Domestically, Mirziyoyev has also presided over a number of important changes, particularly in the economic sector. Uzbekistan had one of the most closed systems in the world under Karimov. Under Mirziyoyev, restrictions on currency transactions have been eased, and more ATMs have been introduced to marketplaces. On Sept. 5, the Uzbek government lifted its currency controls entirely, causing the Uzbek som to lose roughly half its value. The decision was made, in part, to ease currency convertibility, but it was also aimed at curbing black market trading and encouraging foreign investment. In 2016, foreign investment into Uzbekistan stood at just $66 million, compared with $9 billion in neighboring Kazakhstan.

The country’s domestic security policies have also been modified. Under Karimov, Uzbekistan established a highly restrictive environment for opposition activists and political dissidents in the country (often loosely referred to as Islamist militants), as well as a tightly controlled exit visa system for Uzbek citizens traveling outside the country. In August, Mirziyoyev signed a decree abolishing the country’s restrictive exit visa system starting in 2019, and several thousand people have reportedly been removed from the country’s blacklists. In late September, it was announced that the Karimov-era policy of forcing Uzbek citizens to participate in cotton harvests would no longer apply to students, teachers or healthcare workers.

Resistance to Reforms

The changes in Uzbekistan have marked a clear break from the Karimov era. However, not all of them have happened smoothly, and not all are guaranteed to last. Despite his overwhelming victory in the presidential election, Mirziyoyev faces significant resistance from within the political system he’s inherited, particularly from the head of the country’s powerful National Security Service, Rustam Inoyatov, who was rumored to have been in the running for succession to the Uzbek presidency before Mirziyoyev emerged victorious.

Inoyatov’s influence was evident after Mirziyoyev announced Uzbekistan would grant visas allowing citizens from 27 countries (including the United States and several EU countries) to visit Uzbekistan starting in April. That reform was subsequently put off until 2021, a delay likely instituted because of pushback from Inoyatov, who is seen as more conservative and therefore more hesitant to open the country, particularly to the West. The delay appeared to prove Inoyatov’s ability to contend with — and even overrule — Mirziyoyev’s reform efforts.

However, Mirziyoyev’s more recent changes — including the currency reforms and crackdown on black market currency traders and the replacement of a long-serving defense minister with one of his allies — suggest that his power is growing. But while Mirziyoyev may want to sideline Inoyatov completely, he will have to act carefully to avoid blowback from the security services that make up Inoyatov’s power base.

Karimov’s ability to balance the multiple clans and regional factions in the country against one another was key to his longevity as a leader. Upsetting that balance could lead to major instability in Uzbekistan. If frictions between Mirziyoyev and Inoyatov’s security services continue to grow, the Uzbek president risks his reform efforts being undone. Recent unconfirmed reports that members of the National Security Service were planning to assassinate Mirziyoyev are likely overblown but still indicate a substantial resistance to the president’s changes. Additional complications — like calls for secession in the western region of Karakalpakstan, a prolonged economic slowdown and a rapidly growing population amid a generational change — could further undermine Mirziyoyev’s reform efforts.

Geopolitical conditions outside the president’s control could also undermine the longevity of his foreign policy changes. Although Uzbekistan’s relationship with its neighbors has improved, lingering and deep-seated issues of water allocation and border skirmishes in the Fergana Valley will persist. As well, more assertive posturing from Russia and China in Central Asia could force Uzbekistan out of its neutralist balancing act, just as the threat of militancy in the region — especially neighboring Afghanistan — is growing. After Mirziyoyev’s active first year, several factors have the potential to stall or even reverse his attempts to bring reform to Uzbekistan.