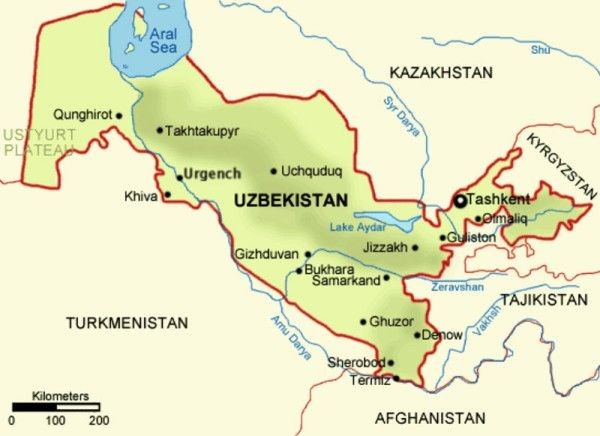

TASHKENT (TCA) — Under the new president, Uzbekistan has embarked upon perhaps the most important economic reform, aimed at making the national currency freely convertible. The plan, if implemented, would help the country attract more foreign investment, as investors would have the possibility to freely exchange their profit in Uzbekistan for hard currency and take it out of the country. We are republishing this article by Gregory Gleason on the issue, originally published by EurasiaNet.org:

Uzbek monetary authorities recently announced an intention to make the country’s national currency, the soum, freely exchangeable. If Uzbek leaders succeed in realizing this goal, it will mark a transformational moment in the country’s post-Soviet economic development.

Preliminary plans to make the Uzbek currency convertible were first aired amid the election of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev last December. The president formalized the idea with a decree this past February that called on the government to promote “economic liberalization aimed at further strengthening macroeconomic stability and the maintenance of high economic growth.”

Given Uzbekistan’s past record on reform, it is understandable that the analyst community greeted overhaul intentions with a healthy dose of skepticism. Uzbek political leaders have a long history of announcing plans for economic reform, including price liberalization, privatization and the shift to a convertible currency. Yet over the past two decades, reforms have tended not to move past the drafting stages. Seemingly, after every announcement of the government’s commitment to economic reform, “complications” arose that slowed and, ultimately, derailed modernization efforts.

Uzbekistan inherited from the Soviet Union a highly centralized, “command” economy, along with a combination of volatile social and political problems. The government, which was led by the late Islam Karimov from independence in 1991 until last September, chose a cautious approach to all reform, stressing instead political stability and continuity.

There are signs that Mirziyoyev’s reform plans are distinctly different from those announced by his predecessor. The February presidential decree, for example, marked a significant departure from Karimov-era practices by explicitly identifying important reform objectives, including price liberalization and the elimination of the country’s multi-tiered exchange mechanisms.

In addition, recent commitments made by the Uzbek government to the International Monetary Fund have gone far beyond what observers expected. For years, Uzbek authorities stonewalled reform recommendations made by international monetary institutions. Now, Tashkent is making it clear that it is listening.

A recent IMF announcement on consultations, for example, refers to an Uzbek commitment to undertake comprehensive economic reform, including “unifying exchange rates and allowing a market-based allocation of foreign exchange resources.” The Uzbek government underscored these commitments by taking difficult steps, including raising the rate the government uses to loan to banks to the level of 14 percent in an effort to contain inflation. Uzbekistan has also mounted a diplomatic offensive with European Union officials to emphasize the seriousness of Tashkent’s reform intentions.

Creating a convertible currency would seem to be the key to success for any reform effort. In the 1990s, amid the economic chaos that accompanied the Soviet collapse, authorities maintained tight control over the soum, ostensibly to prevent capital flight. Now, the ongoing lack of convertibility is choking economic activity and hindering foreign investment.

Under the existing system, Uzbek financial authorities control the soum, establishing an official exchange rate as well as a privileged governmental exchange rate for particular state enterprises and their clients. But because the official rates do not reflect real scarcities, a third exchange rate, the “curb rate” also operates, reflecting the difference between what things cost and what they are worth.

Access to the official government rate enables certain privileged parties to reap great profits from business transactions, causing major market distortions. The black market “curb rate” also fosters economic distortions, encouraging criminal behavior. Financial authorities spend a good deal of time trying to manage the consequences of a distorted economy, including criminality, rather than simply managing financial policies. At the same time, inflation, capital flight, and very low levels of foreign direct investment remain persistent problems.

Transitioning to a market-based economy with a fully tradable currency would probably proceed in several stages. The first step would likely be an effort to unify exchange rates and reorganize state enterprises and state banks. A second major step would be to open channels for investment and liberalizing the ability of investors to transfer profits abroad. This step would require a secondary currency exchange market driven by market fundamentals, rather than government fiscal objectives.

These steps are achievable, but will not be easy to make in the years ahead. They may be complicated by the rising influence of political-economic institutions, such as the Eurasian Economic Union. Another potential roadblock is increasing competition among rival, standard currencies, such as the yuan, which the Chinese government aspires to establish as a global reference currency.