Kazakhstan has intensified its efforts to restore its portion of the former Aral Sea, calling on neighboring Central Asian states to increase their participation in regional environmental cooperation. Once the world’s fourth-largest lake, the Aral Sea has become a symbol of ecological catastrophe. Experts warn that international efforts remain inadequate.

How the Sea Died

Straddling the border between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the Aral Sea began to shrink in the 1960s when large-scale irrigation projects diverted water from its two main tributaries, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, to support cotton production and agriculture. A growing regional population added further strain.

By 1989, the sea had split into the Northern (Small) and Southern (Large) Aral Seas. In 2014, the eastern basin of the Southern Aral Sea dried up completely. Today, the Aralkum Desert occupies much of what was once open water. Kazakhstan has since focused on restoring the Northern Aral Sea.

A ship stranded in the desert, Moynaq, Uzbekistan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

The restoration of the Northern Aral Sea has already yielded visible environmental and social benefits. Rising water levels have lowered salinity, allowing several native fish species to return. Local fisheries, once thought lost, are now active again in communities such as Aralsk. According to the Ministry of Ecology, the annual fish catch in the North Aral has risen more than tenfold since the early 2000s, reviving local employment and boosting food security. Experts note that even small ecological gains have had a profound psychological impact on residents who once witnessed the sea’s disappearance.

Call for Renewed Efforts

On October 15, Kazakhstan called for expanded international cooperation to protect both the Aral and Caspian Seas. First Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Yerzhan Ashikbayev, speaking at the International Astana Think Tank Forum-2025, emphasized Kazakhstan’s contribution to the global climate agenda. He noted that a regional climate summit, set to be held in Astana in 2026, would provide a platform for coordinated strategies and joint decision-making among Central Asian nations.

“Astana also calls for increased international participation in solving environmental problems and preserving the water resources of the Aral and Caspian Seas,” Ashikbayev said.

Earlier, on October 10, Prime Minister Olzhas Bektenov met with senior officials from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan during the second meeting of the Board of the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS), chaired by Kazakhstan. The event highlighted the need for a united regional approach, noting that restoration of the Aral Sea can be achieved through collective action.

Bektenov acknowledged the challenges of the recent growing season, but said regional cooperation had helped maintain a stable water regime in the basin.

“Each country has its own national interests, and we are obliged to defend them and will always do so. But I am convinced that our common strategic, long-term priority is good neighborly relations. In solving everyday short-term tasks, we must not undermine long-term priorities. I think that we will take joint measures to ensure that issues are always resolved on a mutually acceptable and mutually beneficial basis,” he said.

The International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea (IFAS), created in 1993 by the five Central Asian states, is the main framework for joint management of transboundary water resources. Although the fund has facilitated dialogue, it has struggled to overcome divergent national interests. Upstream, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan focus on hydropower, while downstream states rely on irrigation. Under Kazakhstan’s current chairmanship, IFAS is aiming to modernize its work through digital data-sharing and basin-wide monitoring systems designed to improve transparency and trust.

Kazakhstan’s chairmanship of IFAS has prioritized digital transformation and the use of artificial intelligence in water management. Bektenov said these tools will enhance transparency, reduce losses, and improve efficiency. A unified automated system for monitoring and distributing water across the Aral Sea basin is under development.

Expert Opinion: “Only Kazakhstan Is Saving the Aral Sea”

According to the political analyst, Marat Shibutov, Kazakhstan is largely acting alone in efforts to revive the Aral Sea. Writing on social media, he pointed to what he described as a “subtle hint to Kyrgyzstan” in Bektenov’s remarks about giving precedence to long-term goals.

“Right now, Kazakhstan is saving the Aral Sea on its own, both the Small Aral and the Syr Darya delta. We took out a World Bank loan for this, and are paying it back,” Shibutov wrote.

Shibutov warned that downstream efforts are futile without cooperation from upstream countries. “If they don’t release water from the upper reaches, nothing will work. Hence, the appeal to stop hoarding water in reservoirs or discharging it into Arnasai, where capacity is limited. Kazakhstan needs help,” he emphasized.

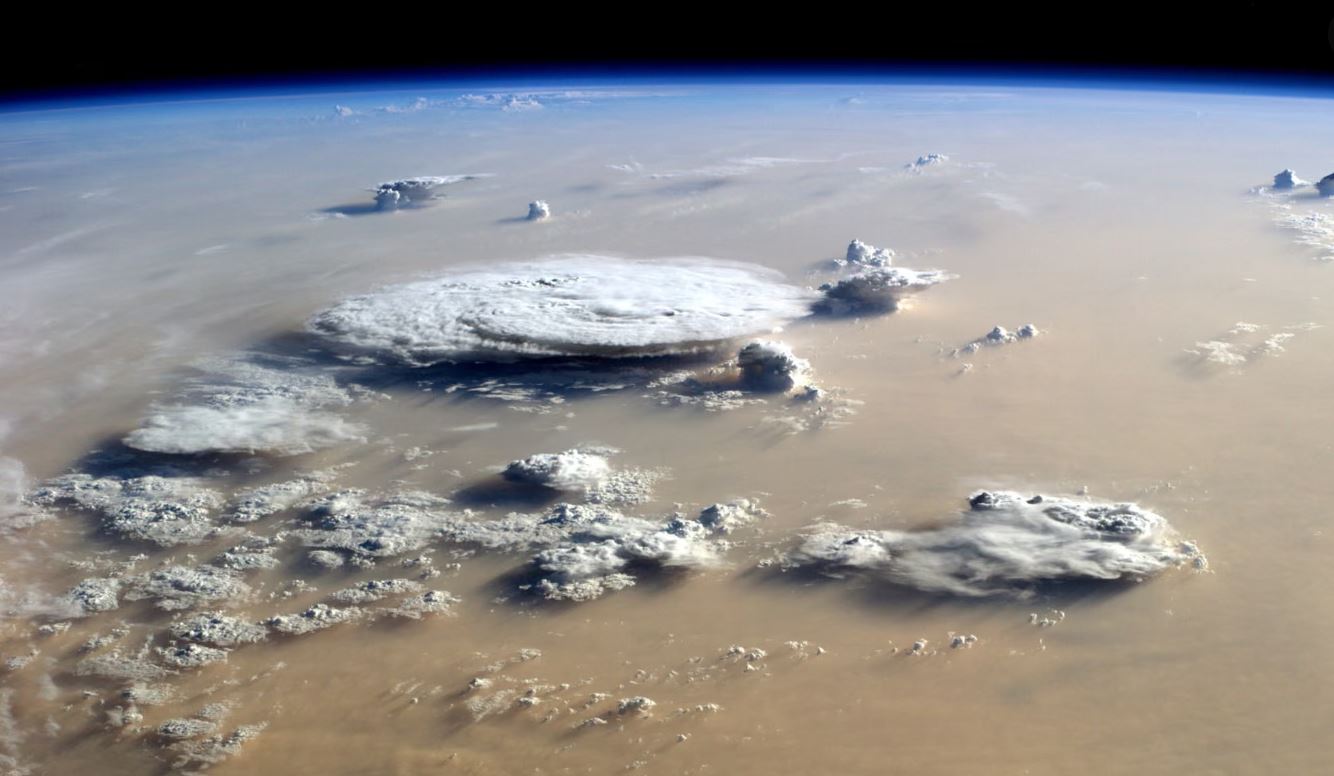

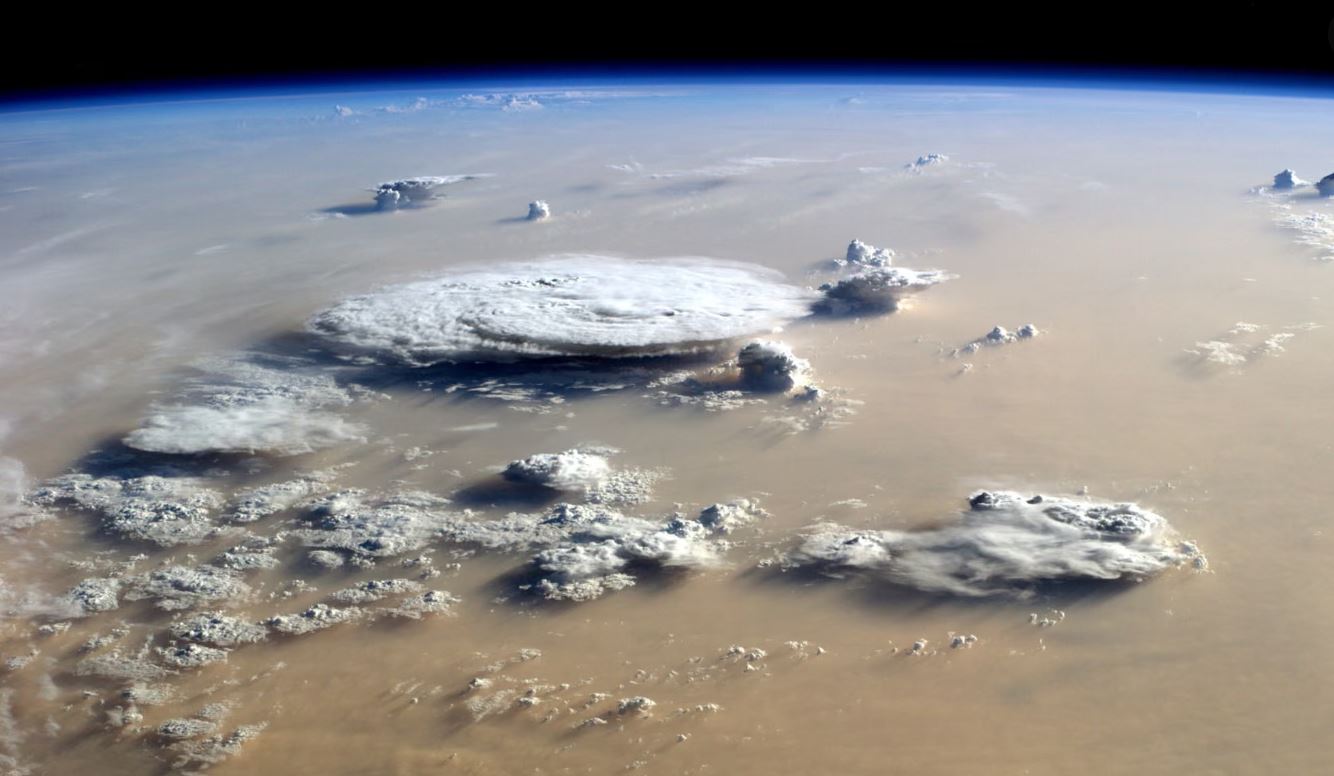

Climate change further complicates water management in the Aral basin. Rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns threaten to reduce the flow of the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers, increasing pressure on already scarce water resources. Frequent droughts and heatwaves worsen evaporation losses, while dust storms from the dried seabed carry salt and pollutants across the region. Kazakhstan frames its Aral Sea initiatives within a broader climate agenda, emphasizing that local restoration supports global adaptation and resilience goals.

A dust storm over the Aral Sea; image: ISS/NASA

Kazakhstan’s Restoration Efforts

Kazakhstan has made the Northern Aral Sea a centerpiece of its environmental revival strategy. The Northern Aral Sea now covers 3,065 square kilometers, an increase of 111 square kilometers since early 2022, according to the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation. Key projects include the preservation of the Kokaral Dam and the restoration of the Syr Darya River delta.

Recent infrastructure work includes the reconstruction of dams between Lake Karashalan and the Syr Darya, the construction of the Tauir protective dam, and the rehabilitation of the Karashalan-1 canal. The Kokaral Dam, which separates the Northern and Southern Aral Seas, is also nearing full restoration. These initiatives aim to preserve the Northern Aral Sea and reduce salinity.

The Kokaral Dam; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

Kazakhstan is also focused on reforestation of the former seabed to improve the regional climate. From 2021 to 2024, afforestation was carried out on 475,000 hectares, with another 428,000 hectares scheduled for 2025.

Across the border, Uzbekistan has pursued more limited measures in the Southern Aral basin. The government has promoted the “Aral Sea Region” as a zone of environmental innovation under UN auspices, focusing on green energy, sustainable agriculture, and afforestation of the dry seabed. However, these projects mainly address socio-economic development rather than hydrological restoration, as the southern basin remains largely beyond recovery under current water conditions.

In the Kazakh port town of Aralsk, the effects of restoration are tangible. Residents once left stranded by the retreating shoreline now see water returning within sight of the town. Small fishing boats have reappeared, and families who had migrated in search of work are beginning to return. “We lost the sea once, but now we have hope again,” said one local fisherman in a recent television interview. Still, locals know that the revival remains fragile, dependent on continued cooperation and careful management across borders.