LONDON (TCA) — Videos have emerged last week of a largely Uzbek group called The Iman Bukhari Jamaat (IBJ) fighting Kurdish forces with mortars, machine guns and crude artillery pieces — another militant group fuelling the fire of war and instability in the nearby regions.

Named after a 8th Century scholar who viewed Sunni Islam as the most pure of faiths, the group emerged in 2013 forged by many veterans who fought in Chechnya. Compared to groups such as the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), the IBJ is a young organisation which stresses the fact that sectarian divisions in Uzbekistan are not improving. The group faced the spotlight last year when videos of young boys being trained in the art of war and jihad were unveiled somewhere in Northern Syria. It was unmistakeable that the children were of Central Asian origin. Worse still, the IBJ have pledged allegiance to Al-Nusra, the active and 20,000 strong wing of Al Qaeda in Syria. Meanwhile, the IMU has aligned itself to the Islamic State further fracturing the volatile sectarian makeup of Uzbekistan.

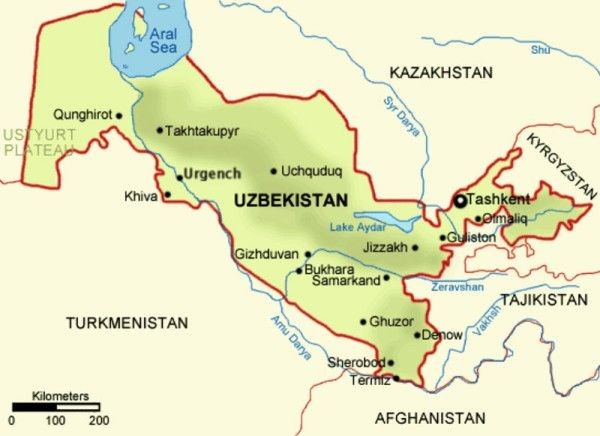

A UK Foreign Office spokesperson said, “Violent extremism amongst individuals of any nationality or ethnicity is a serious concern, which is why the UK strongly endorses the UN Secretary-General’s Plan for Preventing Violent Extremism.” Though bold words have been taken by the international community, the heart of the matter sits in Uzbekistan itself with the potential for further fallout across the continent. Nestled deep in Eastern Uzbekistan is the Ferghana Valley. Once a prosperous collective of the Soviet Union, the valley has been hit hard by cheap Chinese goods and crippling Uzbek-Kyrgyz tension which has resulted in riots and power struggles.

As Islam Karimov solidified his power after the collapse of the USSR, Uzbekistan was deprived of its usual subsidies from Moscow and saw the economy contract by 6% and GDP per capita sink by 30%. This climate of economic turmoil allowed radicalism to fester in Uzbekistan’s most deprived areas. Karimov’s secularisation policies left a sour taste in the mouth of many who remembered the strength Islam had in Uzbekistan previously despite Soviet persecution and its rich history of Islamic scholars, theologians and astronomers. With the founding of the IMU in 1998, the organisation received hefty funding from drug running operations and donations from Al-Qaeda and the Taleban. This allowed them to pay supporters to leaflet at mosques with the potential to earn more than triple the average wage of the time.

With the advent of 9/11, terrorism was seen as the common enemy by much of the world and IMU activity in coordination with the Taleban was targeting heavily by the US and its allies. The Taleban’s strategic retreat against the might of the US military not only launched a guerrilla war but spread their assets all over the region. It was also becoming clear that, though strong, radical Islamic groups did not have the resources to successfully topple the regime in Tashkent and many fighters spread into nearby Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to further their cause there. This diaspora, mostly triggered by events in Afghanistan, has resulted in multiple networks and cells emerging in the region which has created the bedrock for IMU and IBJ activity in Iraq, Syria and Pakistan. Some outlets have speculated that the IMU is in dire need of money following heavy losses at the hands of ISAF in Afghanistan and a rift between them and the Taleban. This change in circumstances has driven them towards the oil rich Islamic State which they swore allegiance to last year.

By nature, the Karimov administration is authoritarian and ruthless. As President of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic for two years, Karimov was determined to remain as head of state during the transition to independent republic. Determined to avoid the violence of the Tajik Civil War in 1992 and the political upheaval of the 2005 Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan, Karimov has governed with an iron fist. As the turmoil in the Middle East grows, the activity of Uzbek radical group intensifies. It is entirely necessary that such groups are undermined and restrained as soon as possible but the way in which the government enacts this may be unsettling.