Turkmenistan Authorities Set Up Fake Bazaars for U.S. Ambassador’s Visit

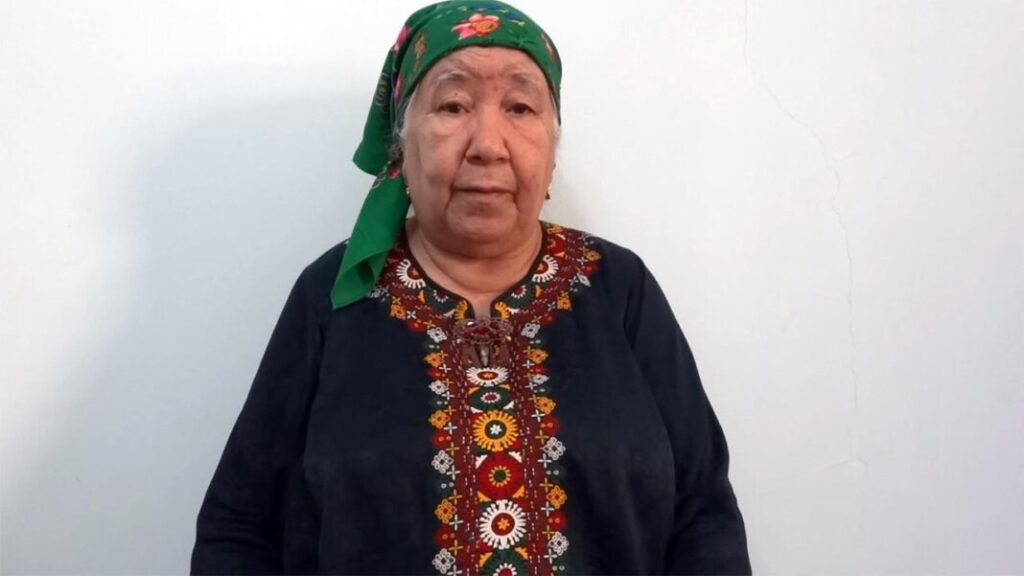

Ahead of U.S. Ambassador to Turkmenistan Elizabeth Rood's visit to the Balkan region, local authorities undertook misleading measures to create a favorable impression of the area. According to Radio Azatlyk, markets in the city of Turkmenbashi were artificially overstocked with food products, and English teachers were deployed as market vendors. On November 22, the U.S. Embassy in Ashgabat reported on Ambassador Rood's visit to Balkan. During her visit, the ambassador met with local business representatives and U.S. companies operating in Turkmenistan, reaffirming the U.S. commitment to expanding investment and commercial ties to promote economic growth and shared prosperity. In preparation for the visit, Turkmenbashi city authorities reportedly instructed English teachers to pose as vendors at local markets, including the Kenar market and other major trading hubs. These measures were designed to create the illusion of a thriving marketplace and well-being among residents. Local sources revealed that the product variety was artificially increased for the occasion, and teachers donned vendor attire to serve shoppers. Such practices are common in Turkmenistan during high-profile visits. In addition to market modifications, Turkmenbashi authorities temporarily banned cars manufactured before 2015 from city roads to present an image of affluence. Observers noted that only new and expensive cars were visible, reinforcing the portrayal of prosperity. While official sources did not confirm visits to local markets by U.S. representatives, local authorities took preventive measures to pre-empt potential criticism. Campaign-style meetings were held in school and cultural assembly halls, where officials from the hakimlik, Trade Union, and Women’s Union instructed residents not to discuss food shortages or economic issues with outsiders, to maintain order in queues for cooking oil, and to report anyone photographing lines.