Women’s rights differ significantly around the world, with progress varying greatly from one country to another. Some states have advanced gender equality significantly through strong legal systems and policies while others are hindered by cultural norms and a lack of political commitment. In Central Asia, each of the young nations has shown a different level of progress on women’s rights and welfare, which requires consideration in individual, regional and global contexts.

Kazakhstan’s new and comprehensive law on strengthening protections for women and children’s rights, adopted on April 15 to international fanfare, highlighted the larger issue of women’s status in Central Asia. The legislation was driven by a 2023 Presidential Decree for a Human Rights Action Plan that brought Kazakhstan in compliance with OECD standards.

Another piece of relatively recent positive news from the region came in April 2023 when Uzbekistan’s parliament passed new legislation specifying domestic violence as a criminal offense under the law and strengthening 2019 provisions that indirectly address domestic violence.

Yet even when there are laws in place to protect women, ensuring their implementation remains critical. For this to happen, laws should first clearly define what constitutes domestic violence so that crimes can be classified and prosecuted as such. As a benchmark, OECD standards close gaps in legally prosecuting such violence by encompassing this classification to include domestic violence against women and children. Kazakhstan has conformed to this norm in its new legislation and thus holds the best practice in the region. Furthermore, to facilitate enforcement and implementation, Kazakhstan’s recent efforts include placing women in key administerial positions in the police force dealing with violent crimes against women. At a larger scale, the country’s Family and Gender Policy foresees increasing the share of women at decision-making levels across the public and private sectors to 30%.

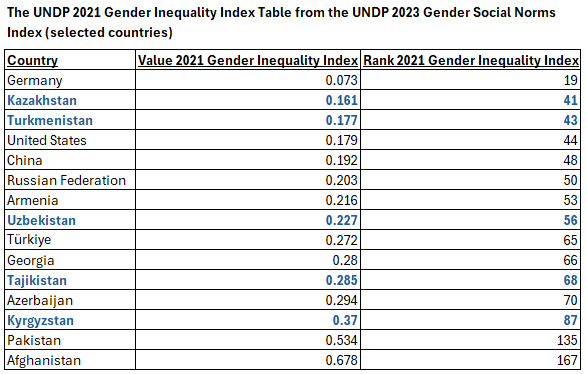

Backing this narrative on Kazakhstan’s upward trajectory from a cultural and social perspective, UNDP’s Gender Social Norms Index Report in 2023 found that Kazakhstan has the lowest levels of gender bias in the region (and incidentally was ranked above the United States in the Gender Inequality Index, which utilized 2021 data as shown below).

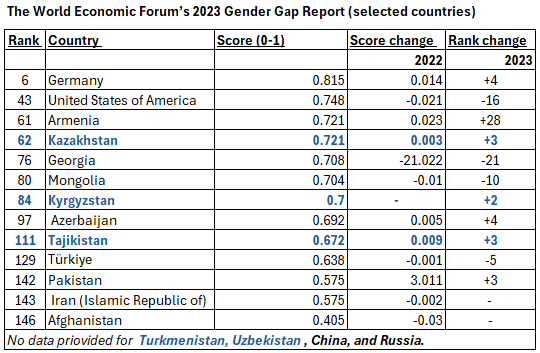

The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2023 also shows significant progress in women’s empowerment in Kazakhstan, which jumped 18 positions in one year to 62nd place globally, particularly through eliminating gender gaps in education levels and increasing women’s political and economic participation.

Two other Central Asian countries have some form of legislation concerning domestic violence against women on paper, but progress on their implementation has not always been encouraging. Kyrgyzstan, for instance, adopted legislation on domestic violence in 2003 as well as a new law on this issue in 2017, which has strengthened protection for victims and sought to improve enforcement mechanisms. But according to reports, the legislation has proven difficult to enforce, and perpetrators may still avoid punishment.

In 2013, Tajikistan also passed a law that specifically addressed domestic violence and included measures for its prevention, protection, and punishment. This, too, appears to have been insufficient as domestic violence has since remained a problem in the country and the law’s reach and enforcement has faced challenges.

Turkmenistan, on the other hand, still lacks any specific legislation targeting domestic violence and has no dedicated mechanism or a national program to prevent it. In addition, recent women’s issues like conducting virginity tests without consent continue to incite international uproar.

Predictably, countries that have strong laws in place and have a stated commitment towards improving women’s standing in the country also occupy the top ranks in Central Asia in terms of their population’s overall happiness, as demonstrated in the 2024 World Happiness Report.

Overall, laws should be considered in the larger context of a country’s desire to change the culture surrounding women’s issues and its dedication to enforcing these laws. While punitive measures are certainly an essential component of any legislation against violence (or on other issues concerning women and children), they must be complemented by an environment promoting cultural transformation and gender equality, as well as support services aimed at addressing the root causes of such problems as domestic violence.

The drivers should not just be moral, but also economic. The World Bank highlights that gender-based violence can cost economies up to 3.7% of their GDP due to increased healthcare costs and lost productivity. OECD projections show that if as many women worked as men by 2030, global GDP could rise by about 12%.

So far in Central Asia, Kazakhstan’s latest initiative sets the benchmark. The establishment of the Central Asian Regional Knowledge Platform by President Tokayev underscores another best practice. Through this medium, Kazakhstan can share its experience in gender empowerment as well as violence prevention and response with other countries in the region.