NEW DELHI (TCA) — This week US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson paid a visit to South Asia. He visited both Islamabad and New Delhi, and made a sudden, secret visit to Afghanistan, too. So tight was the security that there is confusion over where exactly he had his meeting with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani – in Kabul or at the Bagram Air base, which he visited.

This was the first visit by Tillerson to the region since President Donald Trump unveiled his administration’s policy on South Asia and Afghanistan in August. A key component of this new Afghan policy is that he has changed the rules of military engagement. “A core pillar of our new strategy is a shift from a time-based approach to one based on conditions,” the President had announced. He has allowed the “integration of all diplomatic, economic, and military means” to target the enemy, without “micro-management from Washington”.

Trump has also called out Pakistan for its support in providing “safe-havens for terrorist organizations, the Taliban and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond.” This effectively means that US and NATO troops will be at liberty to pursue any action to target the Taliban, ISIS and any other terror group in Afghanistan.

Significantly, it has been reported that following his visit to Afghanistan, Tillerson has said there is a place for moderate elements of the Taliban in Afghanistan’s government as long as they renounce violence and terrorism. This is not a new approach. Successive Afghan governments have tried to reach out to the Afghan Taliban. In an interview to this author, soon after a bloodbath by the Taliban on the streets of Kabul last year Afghan Ambassador to India Dr. Shaida Abdali had said “We do not see the ‘good’ or ‘bad’ Taliban. What we do see is the reconcilable and the irreconcilable Taliban.”

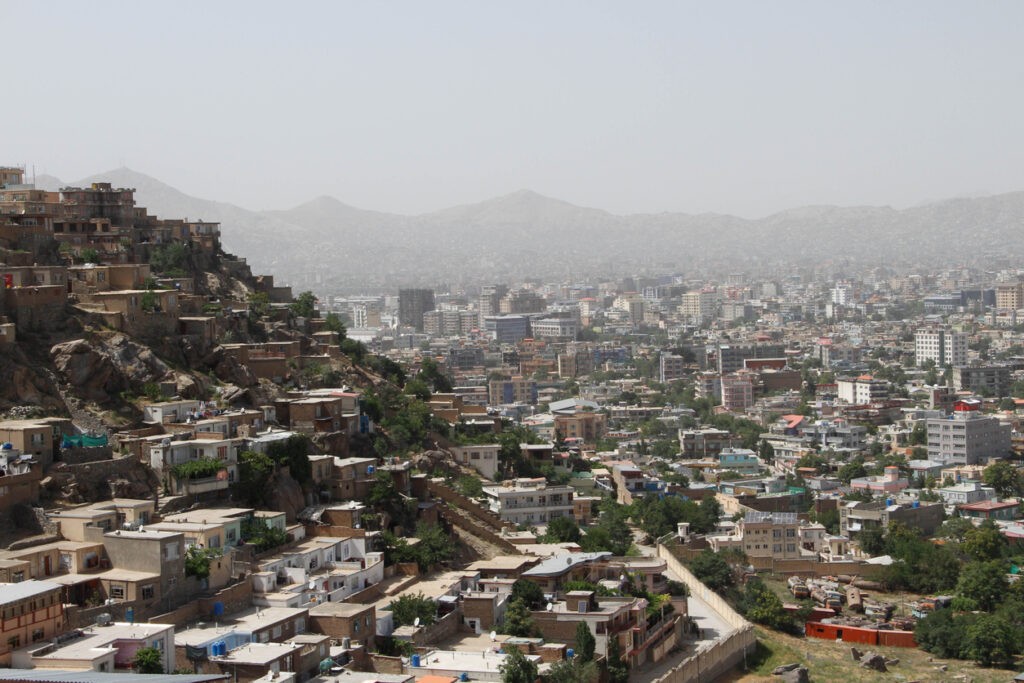

However, the Taliban insists on the departure of all foreign troops from Afghan soil before they agree to sit at the negotiating table, in spite of invitations to talks by powers like Russia and China. No doubt they feel emboldened to thus precondition talks, because of Pakistani support. Besides, the fractiousness of the coalition government in Kabul has contributed to the local support that the Taliban have managed to reclaim in many places because of abuses by representatives of the Afghan state or by those under its protection, like the local war lords. The Taliban today control almost forty per cent of Afghan territory.

This has made other regional players, including Russia and China, also reach out and open channels of communication with them. The Times earlier this month reported that it had learnt from members of the Taliban and Afghan officials that Russia is funding Taliban military operations against NATO in Afghanistan. The Russian Foreign Ministry has strongly repudiated that article saying “We believe that this fake, just as the other items containing false information, are aimed at drawing international attention away from the failure of NATO’s military policy in Afghanistan and are evidence of a resentful attitude to the stabilization efforts by Moscow and its regional partners … in Afghanistan.”

The ministry instead alleges that there are “…continued flights by unmarked helicopters to the Afghan regions controlled by extremists, whom British intelligence services are supporting.”

It is evident that Islamic State of Iraq and Syria militants have found a foothold in Afghanistan and there have been reports of Taliban and other militants moving over to their ranks. There is also worry in the region that with the current defeat of the ISIS in Iraq and Syria, its fighters may flock to Afghanistan where the country’s ungoverned tracts can offer them safe havens. To that end, Iran, whose longtime foe the Taliban has been, to also reach out to it, as it sees it as a lesser evil than ISIS and useful to counter the growth of ISIS there.

The Taliban has different factions and as the US steps up its military operations in Afghanistan, including with greater airpower, with no set deadline, even while the capability of the Afghan National Army is shored up, it is expected that the Taliban’s endurance will be tested and the more amenable factions may come forward to the negotiating table and eschew violence. Under sustained pressure from the US, Pakistan may not be able to keep up its support for the Afghan Taliban.

Pakistani analysts have decried Trump’s new Afghan policy as one which is bound to fail. Pakistan would like to have leverage over Kabul to maintain strategic depth against its arch-rival India on its eastern borders. However, Pakistan’s strategic location, for the movement of US troops and supplies into Afghanistan may not make it easy for the US to assert the kind of pressure it is threatening to. On the other hand, Pakistan’s close links with China can allow it to disdain US warnings.

Meanwhile, Iran, Russia, Pakistan would like to see US and NATO troops leave the region, even as the US becomes embroiled in this ‘new cold war’ with Russia while also alienating Iran with President Trump’s recent decertification of the Iran nuclear deal. It is a terribly complicated situation in which the worst brunt is borne by the Afghan people. It therefore becomes imperative for the government of President Ghani and CEO Abdullah to undertake reforms to provide better governance to the Afghan people. Afghans need to forge a national consciousness. Afghanistan is surviving on foreign aid today and in his speech formulating his Afghan policy, President Trump has also sent a veiled warning to the Afghan government, saying that “America will work with the Afghan government as long as we see determination and progress” and that American “commitment is not unlimited and our support is not a blank check”.

In spite of differences that persist within different stakeholders in Afghanistan and the different regional players, one thing is sure – an unstable Afghanistan is in no one’s interest. It is not only the neighboring and regional states, Pakistan included which embroiled in a war with its own local Pakistani Taliban, that are threatened by Afghan instability, as 9/11 has proved. It is time for all stakeholders to set aside their differences and work to find common ground there.

* Aditi Bhaduri is an independent journalist and political analyst specializing in international affairs and foreign policy. She writes for many national and international publications