Bridging Continents: The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan Railway – A Tale of Opportunities, Challenges, and Controversies

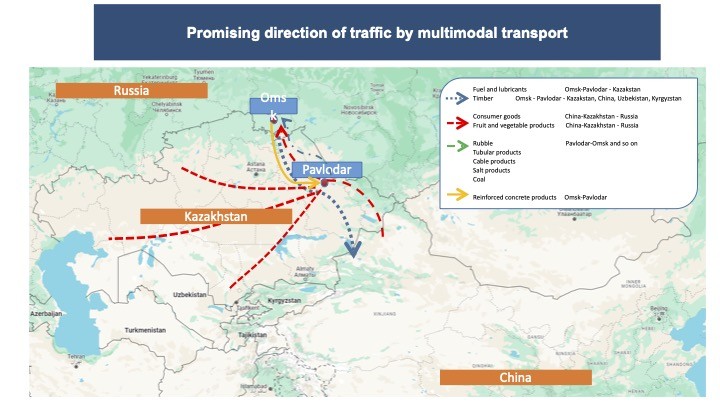

On June 6, 2024, an agreement was signed in Beijing to begin the construction of a railway between China and Uzbekistan which will pass through Kyrgyzstan, a strategic infrastructure project designed to create a new land transport corridor between Central and East Asia. For 27 years, this project remained a pipe-dream. Now, the presidents of the three countries have confidently declared that this railway, with a length of 523 kilometers, is extremely necessary and will be highly profitable for the entire region. However, such sentiments were not always the case, and doubts have long lived in the heads of multiple Kyrgyz presidents. Both Askar Akayev, who ruled the country from 1990 until the revolution in 2005, his successor Kurmanbek Bakiyev, also overthrown as a result of revolution in 2010, and Almazbek Atambayev, were not sure of the benefits of this project. Until 2017, that is, shortly before Atambayev’s resignation and the transfer of power to his, as it seemed to him at that time, reliable friend Sooronbay Jeenbekov, Atambayev was more or less consistent in defending the interests of his country, but later his focus shifted towards China. Why was there such a turn from Atambayev towards Beijing? This later became clear. On January 26, 2018, an accident occurred in the old part of the Bishkek Combined Heat and Power Plant (CHP), which was supposed to have been modernized by that time. This incident served to reveal large-scale corruption and financial violations at the CHP. The contract for implementation of the modernization was signed on July 16, 2013 between the owner of the CHP, Electric Stations OJSC, and the Chinese company, TBEA, in the amount of $386 million dollars. The financing was provided as a loan by a state fund of China, the Export and Import Bank of China (Eximbank), and Kyrgyzstan had to return approximately $500 million including interest. However, after the accident and the transfer of the case to court, it transpired that the real cost of the subhead modernization was a maximum of $250-260 million. Hence, the cost was hugely inflated; as an example, a pair of pliers was invoiced for $640, and fire extinguishers for $1,600. A similar situation occurred with the Datka-Kemin power line, the construction of which began in 2012, when Atambayev was president. The project was implemented by the same Chinese company, TBEA, which carried out work on modernization of the CHP, and the amount cited for the project was the same, $386 million. Again, the loan was issued by Eximbank. As a result of corruption scandals which were revealed in 2019, Atambayev was deprived of presidential immunity and paid with his freedom. Kyrgyzstan’s accumulated debt since its independence in 1991 is estimated at $6.2 billion - 45% of GDP - around $1.7 billion of which is owed to Eximbank. After Sadyr Japarov came to power in November 2020, issues surrounding the Kumtor Gold Mine came to the fore. Discovered by geologists in 1978, the largest open pit gold mine in Central Asia,...