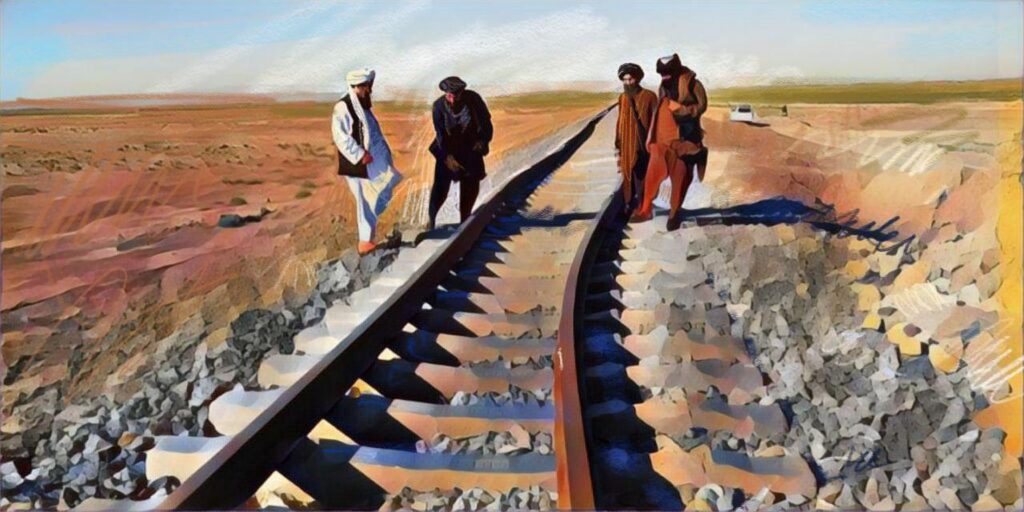

The United States and its allies may be uneasy about the Taliban’s return to power, given their extremist history, continued repression, and the collapse of decades-long Western efforts in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the Taliban is strengthening ties with the Global South—particularly Central Asia—in search of investment for railway infrastructure. For landlocked Central Asian nations, Afghanistan is a key transit point on the shortest route to the Arabian Sea, offering an alternative to routes through Russia, China, or westward via the Caspian.

The war-torn country – located at the crossroads of Central and South Asia – serves as a land bridge between the former Soviet republics and the major markets of the region, including India and Pakistan. This strategic position is why regional actors are eager to invest in the construction of the railway network in Afghanistan, fully aware that the new route would help them achieve at least some of their geopolitical and geoeconomics interest.

Kazakhstani Foreign Minister Murat Nurtleu’s recent visit to Kabul was, according to reports, primarily focused on Afghan railway infrastructure. The largest Central Asian nation economy is reportedly ready to invest $500 million in the construction of the 115km (71 miles) railway from Towrgondi on Afghanistan’s border with Turkmenistan to the city of Herat.

As Taliban railway officials told The Times of Central Asia, the Afghan and Kazakh delegations, who signed a memorandum of understanding on the project, are expected to finalize new agreements and contracts in the coming months. A detailed construction study is expected to be completed by winter, and Afghan authorities anticipate that construction will begin by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, Kabul hopes to reach similar deals with neighboring Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, as well as with Russia and Pakistan. According to Taliban railway experts, these four nations – along with Kazakhstan – are expected to play a major role in the development of the 700-kilometer (approximately 435-mile) railway network in Afghanistan.

The Taliban political officials, on the other hand, see the project as an opportunity for Afghanistan to increase its geopolitical importance.

“It will help us reduce economic dependence and isolation, allowing Afghanistan to integrate more actively into the regional economy,” Muhammad Rehman, the Taliban-appointed Chargé d’Affaires of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan to Kazakhstan, told The Times of Central Asia,

From his perspective, nations investing in Afghan railway infrastructure will become advocates for Afghanistan’s stability. Projects like the construction of the railway, in his view, can transform Afghanistan into a transit hub for regional countries through railway corridors.

“Through the railway, Afghanistan can also import goods at a significantly lower cost, making essential commodities more affordable for its people,” Rahman stressed.

More importantly, the railway opens a route for Central Asian natural resources to reach global markets via the ocean and further enhances the viability of the westward-flowing Middle Corridor. In short, the Afghan rail projects are important for connecting Eurasia. It is, therefore, no coincidence that Kazakhstan – being the richest country in terms of mineral wealth in Central Asia – was the first regional actor to publicly negotiate infrastructure deals with the Taliban.

Fully aware of the importance of Afghanistan as a transit country, Kazakhstan kept its Kabul embassy open under Taliban rule and later accredited Taliban-appointed diplomats to work in Astana. In an attempt to strengthen relations with the new Afghan authorities, in April 2023 Kazakhstan’s Trade Minister Serik Zhumangarin led a delegation to Kabul to discuss trade and deliver humanitarian aid. The following year, Astana removed the Taliban from its national list of banned terrorist organizations, while in June 2025, Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev appointed a Special Representative for Afghanistan, veteran diplomat Yerkin Tukumov. He even described Afghanistan’s integration into regional transport and trade as a “strategic priority.”

As a result of Astana’s diplomatic initiative, Kazakhstan is now one of the ten main trading partners of Afghanistan. Last year, the trade turnover between the two nations amounted to $545.2 million, of which the export of Kazakh products reached $527.7 million.

In the coming months and years, other regional countries are expected to follow Kazakhstan’s path and normalize relations with the Taliban-led Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. After Kyrgyzstan, in September 2024, removed Taliban from its list of terrorist organizations, Bishkek began developing closer economic ties with Afghanistan. Uzbekistan – de facto recognizing the Afghan group as the legitimate government in Kabul – has recently applied to join the North-South corridor through Afghanistan, while Turkmenistan remains engaged in talks with the Taliban on the Trans-Afghanistan pipeline, also known as the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India (TAPI) natural gas pipeline.

The only Central Asian state that openly refuses to do any business with the Taliban, and repeatedly warns of terrorist threats emanating from Afghanistan, is Tajikistan. The former Soviet republic’s approach is no surprise, given that militant groups hostile to the government in Dushanbe (like the Islamic Movement of Tajikistan) have found refuge in Taliban-controlled areas.

The United States and other Western countries also remain skeptical of the Taliban’s regional ambitions. They have not recognized the Taliban government due to its poor human rights record, especially regarding women and minorities. Moreover, on July 8, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution strongly condemning the Taliban’s policies in Afghanistan regarding women and girls. The document was supported by 116 countries, including all Central Asian states. But in spite of critical approach, American envoys have in 2023 met Taliban representatives in Doha and elsewhere to discuss issues like humanitarian aid and security commitments.

Mars Sariyev, a Kyrgyz political scientist and regional security expert, believes that the US plans eventually to return to Afghanistan – not through a military campaign, but through diplomacy and economy.

“It is a matter of time. The United States will use Afghanistan and the Taliban movement to shift the balance of geopolitical forces in Central Asia. For instance, to divide Russia and China, and to strengthen its own influence in the region,” Sariyev stressed.

Alternatively, the U.S. may see long-term value in Afghanistan as a stable transit hub linking Central Asia to global markets—a goal it pursued during its rebuilding efforts in the country. Secular, modernizing states like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan could support this vision by promoting economic ties and regional integration, helping reduce Afghanistan’s isolation and enhance stability.

Meanwhile, Afghanistan’s rulers are expected to focus on developing stronger economic ties with Central Asian states, particularly in the field of railway construction.

“In the near future, we are likely to witness more agreements similar to the Kazakhstan–Afghanistan railway project from Towrgondi to Herat, which will further integrate Afghanistan into regional trade networks,” Rahman concluded.

But since talks are reportedly underway to initiate direct flights between Afghanistan and Kazakhstan, for the foreseeable future Kabul will almost certainly prioritize its relations with Astana – the Taliban’s major partner in the region.