In the so-called New Great Game, Central Asia is no longer a mere backdrop; with its strategic location, massive oil and gas reserves, and newfound deposits of critical raw materials, it’s a key player. In stark contrast to events in the 19th century, this time, Central Asia finds itself courted by four great powers – China, the EU, the U.S., and Russia – instead of caught in the crosshairs of conquest. The region finds itself with agency.

However, the original Great Game was anything but fair play. Comprising vast steppes, nomadic horsemen, descendants of Genghis Khan’s Great Horde, and a lone nation of Persians, during the 19th century, the once-thriving Silk Road states became entangled in a high-stakes battle of expansion and espionage between Britain and Russia. Afghanistan became the buffer zone, while the rest of the region fell under Russian control, vanishing behind what became known as the “Iron Curtain” for almost a century.

The term “Great Game” was first coined by British intelligence officer Arthur Conolly in the 19th century, during his travels through the fiercely contested region between the Caucasus and the Khyber. He used it in a letter to describe the geopolitical chessboard unfolding before him. While Conolly introduced the idea, it was Rudyard Kipling who made it famous in his 1904 novel Kim, depicting the contest as the epic power clash between Tsarist Russia and the British Empire over India.

Conolly’s reports impressed both Calcutta and London, highlighting Afghanistan’s strategic importance. Britain pledged to win over Afghan leaders — through diplomacy, if possible, and by force, if necessary.

The Afghan rulers found themselves caught in a barrage of imperial ambition, as the British and Russian Empires played on their vulnerabilities to serve their own strategic goals. Former Ambassador Sergio Romano summed it up perfectly in I Luoghi della Storia: “The Afghans spent much of the 19th century locked in a diplomatic and military chess match with the great powers — the infamous ‘Great Game,’ where the key move was turning the Russians against the Brits and the Brits against the Russians.”

The Great Game can be said to have been initiated on January 12, 1830, when Lord Ellenborough, President of the Board of Control for India, instructed Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General, to create a new trade route to the Emirate of Bukhara. Britain aimed to dominate Afghanistan, turning it into a protectorate, while using the Ottoman Empire, Persian Empire, Khanate of Khiva, and Emirate of Bukhara as buffer states.

This strategy was designed to safeguard India and key British sea trade routes, blocking Russia from accessing the Persian Gulf or the Indian Ocean. Russia countered by proposing Afghanistan as a neutral zone. The ensuing conflicts included the disastrous First Anglo-Afghan War (1838), the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845), the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848), the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878), and Russia’s annexation of Kokand.

At the start of the Central Asian power struggle, both Britain and Russia had scant knowledge of the region’s people, terrain, or climate. The Great Game revolved around gathering intelligence, charting routes, identifying the families controlling the land, and mapping uncharted territories. Undercover agents produced maps while monitoring Russian troop movements, just as the Russians kept tabs on British activities. The contest was as much about information as it was about influence.

Stoddart and Connolly; image: Davide Mauro

The mastermind behind the phrase and policy of the Great Game, Arthur Conolly, along with his colleague Charles Stoddard, stood at the heart of high-stakes intelligence efforts that ignited intense and dramatic events.

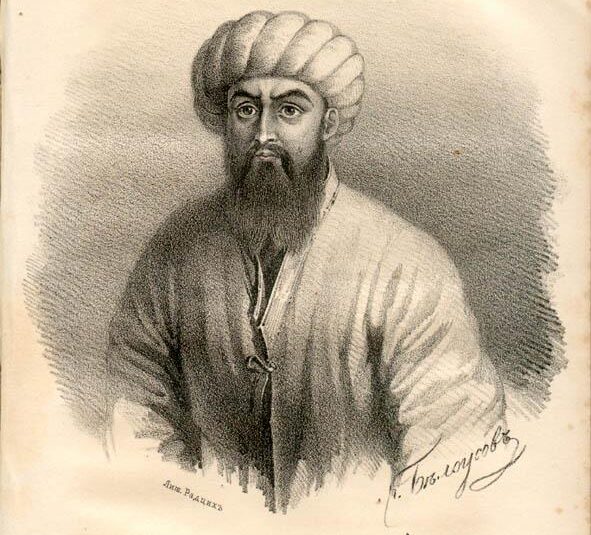

Taking power in Bukhara in 1827, Emir Nasrullah Khan cemented his reputation as the most ruthless of the Mangit Khans. His reign was marked by bloodshed, including the execution of twenty-eight close family members, among them three of his daughters, whom he killed to preserve their virginity. Nasrullah showed no hesitation in eliminating dissent, famously splitting a courtier in half with an axe over a minor irritation. Enforcing Sharia law with brutal zeal, having his men randomly quiz citizens on Quranic verses and meting out merciless punishments for mistakes, he sank further into infamy by encouraging impoverished families to sell their children to satisfy his depraved desires.

Nasrullah Khan

During the height of the Great Game, Colonel Charles Stoddart entered the court of the Bukharan Emir. His mission was both clear and ambitious. First, he sought to convince the Emir to release Russian slaves, cutting off the Tsar’s excuse for annexing Bukhara. Second, he aimed to secure a treaty of friendship with Britain. The secrecy surrounding the Bukharan court was legendary. However, Alexander Burnes — an explorer and cousin of poet Robert Burns — had documented one crucial detail: only Muslims were permitted to ride horses within the city walls.

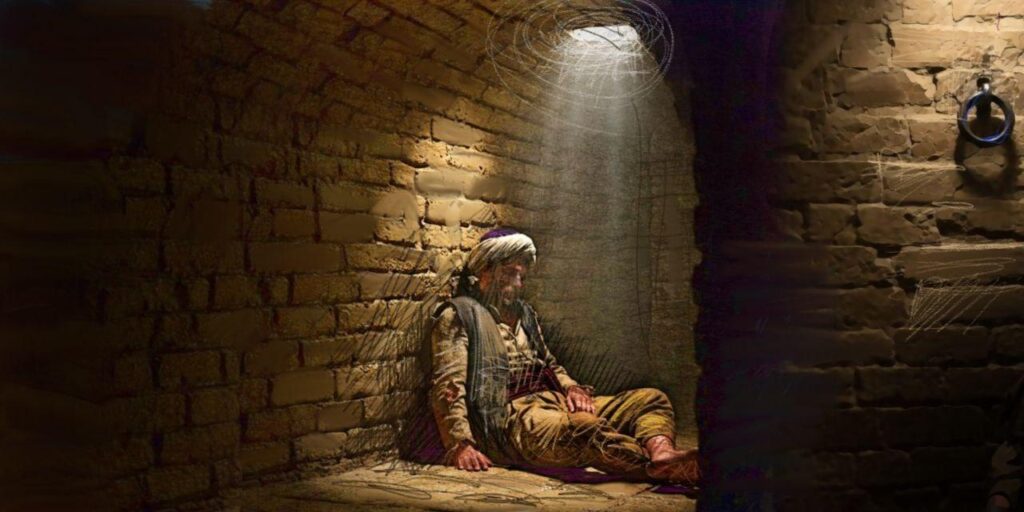

Stoddart sealed his fate with his arrogance and missteps. Staying mounted on his horse, bringing no gifts, and refusing to bow, he struck out at an attendant trying to prompt his deference. Adding insult to injury, his letter of introduction lacked the Queen’s signature. To make matters worse, Nasrullah had just received a damning dispatch from the Emir of Herat, accusing Stoddart of espionage and calling for his execution. What followed was a grim descent into the Emirate’s infamous dungeon, the Bug Pit — a diseased cesspool riddled with scorpions, rats, and specially bred vermin that thrived in the city’s filth.

The Bug Pit; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

The British, the Turkish Sultans, and the rulers of Khiva and Kokand all demanded Stoddart’s release; even the Russians joined in — but none of it worked. When British forces captured Kabul in July 1839, the Emir, gripped by fear of invasion, issued Stoddart a brutal ultimatum: convert to Islam or die. Battered, desperate, and out of options, Stoddart gave in. After being bathed and circumcised, he moved into the chief of police’s home, gaining a sliver of freedom. He began praying at the Kalon Mosque and even managed to sneak letters back home to Norwich. “This Ameer is mad,” he wrote to his family.

With the British showing no intention of advancing on Bukhara and his letter to Queen Victoria left unanswered, Nasrullah subjected Stoddart to a year of imprisonment in and out of the dreaded Bug Pit on a whim. Captain Arthur Conolly, a fervent Evangelical Christian, was the most incensed by Stoddart’s treatment. Fueled by a vision of uniting the region under the British flag, abolishing slavery, and “civilizing” the locals, Conolly believed he could outmaneuver Russian influence by persuading local rulers to align with Britain. At thirty-three and nursing a broken heart after being jilted, he channeled his zeal into this ambitious mission.

With Stoddart’s cause boosting his appeal, Conolly dismissed Burnes’ sharp remark that only the “wand of a Prospero” could unify Central Asia. His bold plan ultimately won approval from his cousin, William MacNaughton, the British envoy in Kabul. Tragically, a year later, MacNaughton stood by as Alexander Burnes, Britain’s foremost expert on the region, was brutally torn apart. MacNaughton met an equally gruesome end, his torso displayed on a meat hook in the heart of Kabul, while his severed limbs and head were paraded triumphantly through the streets.

In September 1840, Conolly set out for Khiva. Although he was well received, he left without assurances and was firmly cautioned against visiting Bukhara. Moving onward to Kokand, he found hospitality but no treaty and yet another warning to steer clear of Bukhara. During this time, he received letters from Stoddart, who wrote, “the favor of the Ameer is increased towards me these days. I believe you will be well treated here.”

Conolly reached Bukhara in November 1841, nearly three years after Stoddart had been imprisoned. Nasrullah’s spies had been shadowing his every move for weeks, intrigued by his visits to their fiercest enemies. Despite this, the infamous Butcher of Bukhara played it safe, greeting Conolly warmly and pressing him for the Queen’s long-awaited reply. Conolly reassured him that the message would arrive soon, speaking with the authority of the sovereign’s representative.

While Stoddart and Conolly endured house arrest, a long-awaited message arrived — not from the Queen, but from Lord Palmerston. It confirmed the Emir’s correspondence had been received and passed not to the Queen but to the Governor General of India. This insult enraged Nasrullah, and tensions escalated further when another message from Herat accused Captain “Khan Ali” of espionage. Conolly soon found himself thrown into the infamous Bug Pit, tasting its horrors for the first time. Stoddart, meanwhile, had likely lost track of how many times he’d been imprisoned.

The Zindon, where Stoddart and Conolly were imprisoned; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland

The Governor General of India finally wrote to demand the release of Stoddart and Conolly, referring to them as “private travelers” — diplomatic code for agents the British refused to acknowledge. Paired with the humiliating British retreat in Afghanistan, this convinced Nasrullah that he could act without consequence.

Fresh from crushing the Khanate of Kokand, brimming from the violence of his triumph, Nasrullah hauled his captives Stoddart and Conolly to the Registan on June 24, 1842, four agonizing years into their imprisonment. Forced to dig their own graves in front of a captivated crowd, the starving, mutilated officers — scarred and with flesh chewed from their bones — clung to each other, sobbing. Drummers pounded a somber dirge as their hands were tied, and they were shoved to their knees. Stoddart, a convert to Islam, likely earned the grim privilege of having his throat slit.

Conolly, however, was given a final taunt. He was promised mercy if he converted to Islam by Nasrullah’s executioner, the so-called “Shadow of God.” He rejected the offer with resolve, exclaiming, “Colonel Stoddart has been a Muslim for three years, and you have killed him. I will not become one, and I am ready to die.” His head was severed moments later. The pair’s bodies were dumped into an unmarked grave beneath the Registan.

With no news of the doomed officers forthcoming, their friends gathered funds and dispatched Joseph Wolff, a peculiar clergyman, to uncover their fate. Arriving in Bukhara in 1845, Wolff narrowly escaped their fate not by wit or force but by sheer absurdity. His full canonical robes amused the Emir so thoroughly that Nasrullah spared his life, even inviting his “musical band of Hindoos” to serenade Wolff with “God Save the Queen.” Nasrullah Khan would rule undisturbed for another 15 years, meeting his end not by the sword but peacefully in his sleep.

The Great Game drew to a close in the early 20th century, brought on by pivotal international shifts. The Russian Empire, drained by the costly Russo-Japanese War (1904–1906), lacked the resources to sustain its Central Asian ambitions. Tsar Nicholas II faced mounting financial and military constraints, halting Russian momentum. The Anglo-Russian Convention of August 31, 1907, marked the official end of a nearly a century-long rivalry. With Afghanistan secured as a British protectorate, it brought respite to the geopolitical chess game between the two empires.

The Great Game ended without a victor, leaving behind shattered economies, silenced political movements, countless lost lives, and a chilling legacy.