Kazakh literature is filled with towering figures who have shaped the nation’s cultural and spiritual identity. Among them, Abai Qunanbaiuly (1845–1904) remains the most iconic. A poet, philosopher, and intellectual of global stature, Abai left behind a legacy that continues to resonate within world literature. As Kazakhstan celebrates the 180th anniversary of his birth, it is a fitting moment to explore how his influence extended far beyond the steppe, reaching as far as the United States.

George Kennan: The American Who Introduced Abai to the World

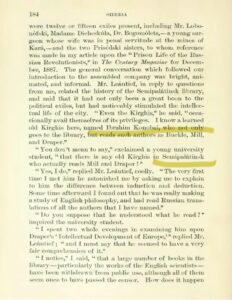

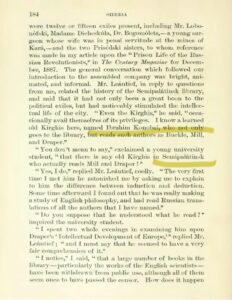

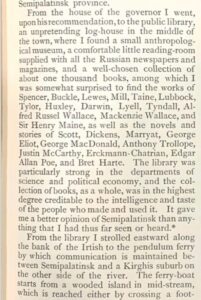

In 1885, American journalist George Kennan visited Semey (then Semipalatinsk) and was deeply impressed by the city’s public library. To his surprise, local Kazakhs actively borrowed and read books, a rare sight for that time and region. In his influential work Siberia and the Exile System, Kennan specifically mentioned Abai, marking one of the earliest references to the Kazakh thinker in Western literature.

Kennan’s account stands out for its authenticity. It is based not on secondhand stories but on direct observation. His writings confirm Abai’s presence in Semey’s intellectual life and suggest that the poet had begun to attract attention well beyond the Kazakh steppe.

Credit «Siberia and the Exile System», by George Kennan

From Kennan’s descriptions, we gain insight into what Abai read, who his associates were, and how his worldview aligned with major thinkers of the time.

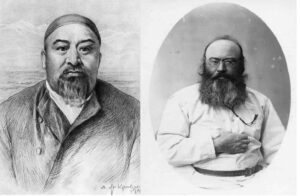

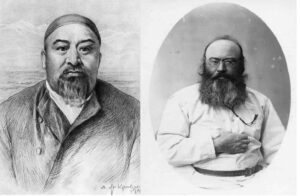

Abai’s intellectual growth was greatly influenced by E. P. Mikhaelis, a Russian political exile and lifelong friend. Under Mikhaelis’s guidance, Abai refined his reading habits and began a new phase of self-education. Through Mikhaelis, he was introduced to other exiled Russian intellectuals such as S. S. Gross, A. A. Leontiev, and N. I. Dolgopolov.

These thinkers were struck by Abai’s intellectual depth, civic engagement, and dedication to the betterment of his people. In return, Abai introduced them to Kazakh culture, history, and oral traditions, becoming a cultural bridge between East and West.

Аbai and E.P. Mikhaelis

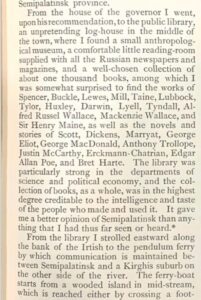

Kennan also described the library in Semey, where Abai was a frequent visitor and reader. Since the original excerpt is in English, it is often shared as an image in historical archives rather than a transcription.

Credit «Siberia and the Exile System», by George Kennan

The exterior appearance of the library in Semey where Abai was a reader

Abai’s Songs and Wesleyan University

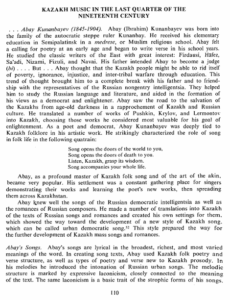

Abai’s influence extended not only through literature but also through music. In 1970, Wesleyan University Press in Connecticut published Music of Central Asia: Essays on the History of Music of the Peoples of the USSR, a groundbreaking volume by V. Belyaev and other scholars. The book includes a chapter titled Kazakh Music: From the 15th Century to the Mid-18th Century, which devotes special attention to Abai’s musical legacy.

Belyaev describes Abai as a progressive thinker and a voice for enlightenment, quoting one of his famous verses:

“Song opens the doors of the world to you,

Song opens the death to you.

Listen, Kazakh, grasp its wisdom.

Song accompanies you your whole life.”

In the section Abai’s Songs, Belyaev explores the emotional range and poetic craftsmanship of Abai’s music. The poet merged Kazakh folk forms with Russian melodic influences, creating a distinctive style that aligned lyrical meaning with melodic structure.

One example is the song “Ayttim Salem, Qalamkas,” whose heartfelt lyrics convey themes of love, longing, and human connection. Another is the renowned “Kózimnіń qarasy” (“The Black of My Eye”), notable for its traditional aaba verse form and expressive melody.

Abai’s poem Segiz Ayaq (“The Eight-Liner”) is also discussed for its moral and ethical themes. Written in an innovative eight-line stanza with a unique metrical structure (558+558+88) and a rhyme pattern (aab ccb dd), it exemplifies Abai’s command of both form and content.

While his music is now receiving long-overdue recognition, much of Abai’s poetry and philosophy remains underexplored in international circles.

Abai’s commitment to education, self-awareness, and moral integrity defines him as more than a national poet. He is a universal thinker. As Professor Tursyn Zhurtbay puts it:

“We participate in global intellectual culture through Abai. He is the moral compass of our people. Every Kazakh should hold their own image of Abai in their heart.”

The only lifetime portrait of Abаi. Painter Lobanovsky P.D. 1887 y. Pencil

Abai with family members – wife Erkezhan, sons Turagul and Magauiya, grandsons – Pakizat, Abubakir and his wife Kamaliya. Semey city,1903

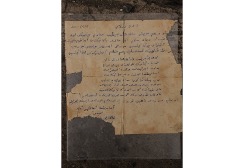

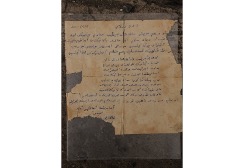

The original letter of Abai to his son Magauiya.

Arabic script. 1896 y.

From the personal fund of Musakhan Baltakaiuly.

Museum of Abai in Semey

To truly honor Abai is to engage deeply with his ideas. His vision of harmony between heart, will, and reason remains deeply relevant. As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, his wisdom continues to echo, urging us to look inward while building bridges outward.

Abai’s words are not relics of the past. They are living guides for the future. The responsibility now falls to us to read, reflect, and carry forward the message of one of Kazakhstan’s greatest minds.