Central Asia, spanning an area from the Caspian Sea in the west to China in the east and from Afghanistan in the south to Russia in the north, is rapidly emerging as a significant economic block. Comprising five post-Soviet states — Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan — this region is distinguished by its rich natural resources and strategic geographic position, as well as its natural beauty and cultural heritage. With a combined population of around 75 million people, Central Asia has emerged as a dynamically developing market that is increasingly attracting global interest.

The transformation unfolding in Central Asia holds both promise and significant challenges for its residents and foreign investors alike. This shift is driven by increasing calls for political reform, the dynamism of a youthful population, and an imperative for sustainable development alongside the pressing need to diversify economic bases.

Structural changes following independence in 1991 set the stage for robust growth from 2000s onward

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Central Asian countries faced the challenge of transitioning from centrally-planned to market-oriented economies. This period was marked by significant economic difficulties across the region including negative GDP growth and hyperinflation, compounded by the complexities of privatization, legal reforms, and both social and political instability. The nations responded with different development strategies aimed at market liberalization, infrastructure improvement, and the utilization of natural resources.

By 2000, Central Asia experienced a noticeable economic resurgence, marking a striking contrast to the conditions in 1991. In that year, Uzbekistan’s GDP growth was at -0.5%, Kyrgyzstan at -7.9%, and Kazakhstan at -11%. A decade later, these countries reported positive growth rates of 4.2%, 5.3%, and 13.5%, respectively. This remarkable turnaround can be attributed to the “low base effect,” where the initially low economic indicators set the stage for significant improvements over time.

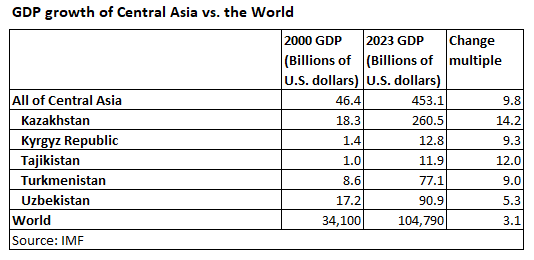

The total GDP of Central Asian countries has grown seven times since the beginning of the 2000s. In comparison with the global economic growth rate of +2.6% annually, the Central Asian region grew by an average of 6.2% between 2000 and 2023 according to IMF data.

All Central Asian states are forecasted to outpace the IMF’s projected growth rate for emerging markets and developing economies 2024 which stands at 4.2%; however, actual growth will depend on reforms and foreign investment. Kazakhstan has set the highest growth goal with a five-year target GDP increase to $450 billion, which would require an achievable but challenging 6% annual growth.

As illustrated below, Kazakhstan stands out as the economic powerhouse of Central Asia with a GDP almost 1.5 times that of all the other countries combined.

Labor markets: Optimal demographics for growth and innovation

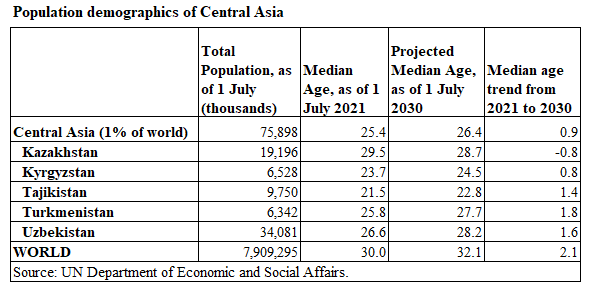

According to United Nations data, approximately 75 million people live in Central Asia, representing 1% of the world’s population. Relative to the global median age, all of Central Asia boasts a young population.

A youthful population fuels economic growth by replenishing the workforce, driving innovation, and expanding consumer markets. It supports older demographics through social systems and can significantly boost a country’s economy if coupled with investments in education, healthcare, and job creation.

Among the five republics, Tajikistan has the youngest median age at 21.5 years. Kazakhstan has the highest at 29.5; however, it is the only state trending towards a younger median age.

With such an age distribution, Central Asian societies’ demands for qualitative changes in the social sphere and the labor market are both expected and justified. The younger generation strives to improve their well-being through access to quality education and promising jobs, and, as a result, decent wages.

Central Asia’s young population is at risk of being underutilized or getting caught in the “middle income trap,” where a country reaches a certain income level but can’t advance to a high-income status, typically because of stagnant productivity, lack of innovation, and insufficient competitiveness. Escaping this trap for Central Asia entails a strategic investment in advanced education and innovation, the building blocks of high-value industries that can drive a sustainable economic expansion.

In Kazakhstan, for example, more than 54,500 students are currently enrolled in various studies of emerging technologies, including 31,400 officials undergoing professional training. In 2023, more than 13,000 graduates of higher and postgraduate education had a 78.7% employment rate, according to data provided by Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Science and Education.

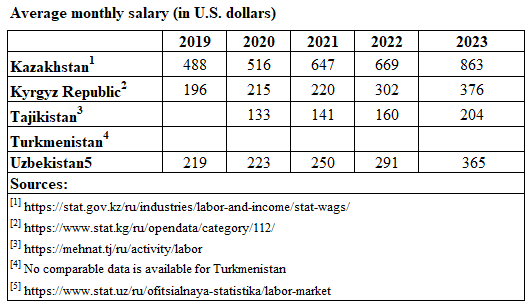

All five states face the dual challenge of ensuring that their workforce remains competitive on a global scale while also providing fair wages to their employees. Kazakhstan offers the highest wages in the region at $863 per month.

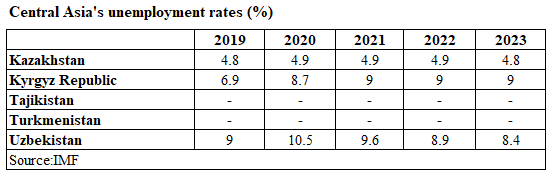

Over the past five years, despite the Covid-19 crisis, the average salaries in Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan have almost doubled. At the same time, the epidemic had a strong impact on their level of employment. Between 2020 and 2022, there was a sensitive increase in the unemployment rate (the number of people actively seeking work but are unable to find employment). Economies are still recovering from the pandemic.

The labor markets of these countries responded to the above challenges by adjusting the conditions for their workers, such as through switching to remote work, providing free retraining opportunities to acquire new skills and successful employment, and giving support to self-employed individuals and small and medium-sized businesses.

However, according to data for 2023, not all countries in the region managed to stabilize the situation in the same manner. In Kyrgyzstan, the unemployment rate remains at 9% (a value unchanged for three years) and Uzbekistan is at 8.4%, while in Kazakhstan, the unemployment rate has returned to the pre-crisis level of 4.8%. There is no publicly available data for Turkmenistan and Tajikistan for 2023.

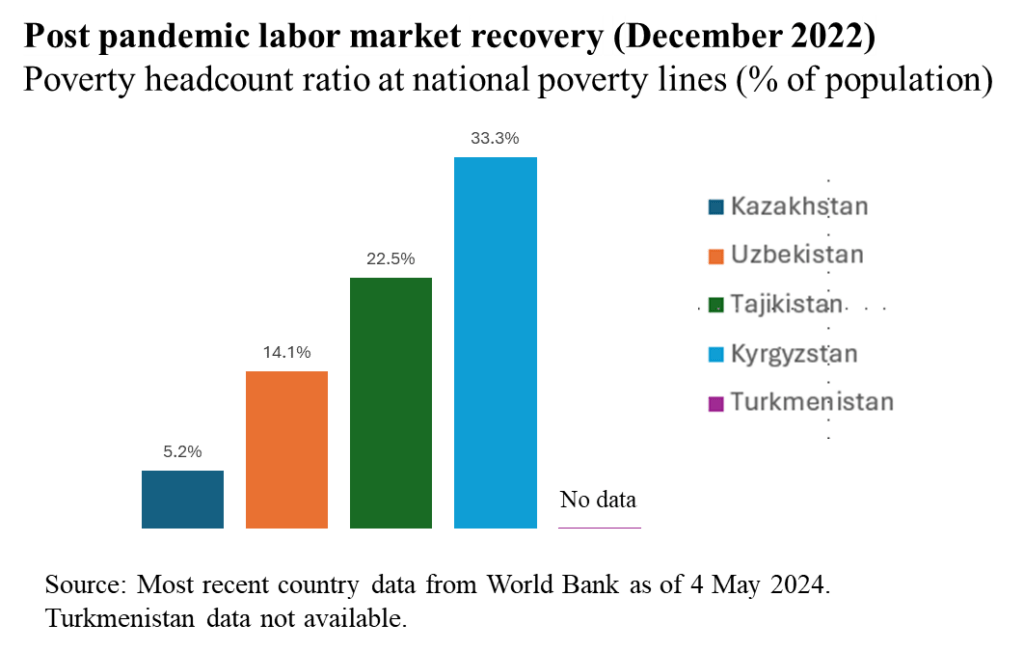

The pandemic required restrictions to economic activity which exacerbated social inequality in the Central Asia region. According to the World Bank World Development Indicators, Kyrgyzstan suffered the most. In 2019, a fifth of the republic’s population (20.1%) was below the poverty line; in 2022, a third of the country was in this category (33.3%). In Uzbekistan, poverty level remains at 14.1% from a high of 17% in 2021. In Tajikistan, it stands at 22.5%. Relatively speaking, Kazakhstan has prevented social inequalities brought on by the pandemic period with poverty rate rising just 1% from 4.3% to 5.3% and falling to 5.2% in 2022, the lowest among Central Asian countries providing statistics.

Retooling the economy for sustainable development

Central Asian countries are signatories to key environmental multilateral initiatives, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), Ramsar Convention, Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, and the Vienna Convention for the Ozone Layer along with its Montreal Protocol. These agreements address a wide range of environmental issues such as climate change, biodiversity conservation, desertification, wetland protection, persistent organic pollutants, and ozone layer preservation. Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have committed to the UN-led Global Methane Pledge, which aims to reduce methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030 compared to 2020 levels.

Each country has taken proactive sustainability measures considering their natural resources. Kazakhstan, for example, has initiated a Joint Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) to bolster its contribution of essential minerals for wind turbines, batteries and other renewable energy systems and supply the global shift towards renewable energy technologies. Kazakhstan is set to increase its uranium production as the world’s largest supplier and is a burgeoning producer of green hydrogen. It has also planned to launch the so-called Fast Track, or “green corridor,” which will simplify and significantly speed up the entire process – from registration to commissioning of facilities – for new projects worth $15 million or more.

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have focused on preserving their rich biodiversity and water resources. Tajikistan’s efforts to promote the International Decade for Action “Water for Sustainable Development” (2018–2028) highlight its commitment to this cause. Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have focused on combating desertification and deforestation through ambitious tree-planting campaigns.

Economic diversification as a key goal for the region

For Central Asian countries, traditionally reliant on natural resources and agriculture, diversification is crucial to mitigate the risks of volatile commodity prices and to transition towards more stable and sustainable economic models that can support development and reduce poverty.

Uzbekistan, for instance, is reducing its dependency on cotton by increasing the production of fruits, vegetables, and grains, while also tapping into its rich cultural heritage to boost the tourism sector.

Kazakhstan has already launched some 300 projects in non-resource sectors, with plans to commission another 400 projects in 2024. The country is creating favorable conditions for small and medium-sized businesses and is incentivizing businesses to produce and export goods with high added values, such as steel, machinery, and equipment.

Turkmenistan, for its part, is enhancing natural gas exports with new gas chemical products while modernizing its agricultural industry. The country is also promoting its textile sector.

Tajikistan is concentrating on exploiting its hydropower potential for electricity exports, modernizing agriculture to enhance food security and export capacity, expanding its mining sector beyond traditional outputs, and developing tourism by capitalizing on its natural and cultural heritage.

And finally, Kyrgyzstan is developing its services sector, creative economy, and agricultural exports with the support of USAID and Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Central Asian nations are boosting their global competitiveness and diversifying their economies by creating specialized economic zones tailored to their unique strategies and capabilities. For instance, Kazakhstan has 14 special economic zones (SEZs) strategically designed to enhance the country’s position as a key trade and logistics hub, especially considering its pivotal location along the Belt and Road Initiative. This initiative aims to improve connectivity and cooperation between East Asia, Europe, and East Africa through trade and infrastructure projects. To date, 354 projects have been implemented in the territory of 14 SEZs, totaling over 7.5 trillion tenge (around $16.9 billion) and employing more than 25,500 people. Some 2.9 trillion tenge (around $6.5 billion) were attracted in investments, according to Kazakhstan’s Minister of Industry and Construction, Kanat Sharlapayev.

Uzbekistan has likewise established 23 Free Economic Zones (FEZs) and approximately 502 specialized small industrial zones (SIZs) across the nation’s various regions to enhance foreign direct investment (FDI) attraction. General Motors Uzbekistan (now known as UzAuto Motors), for example, operates in the special economic zone “Jizzakh.”

Kyrgyzstan’s Maimak Free Economic Zone, located near the border with China, aims to facilitate trade and logistics. China has become the main source of Kyrgyz imports while Russia has emerged as the primary destination for exports, including re-exports.

Tajikistan has four Free Economic Zones with “Dangara” zone slated to domicile a joint oil refinery with Azerbaijan. For its part, Turkmenistan has created the Awaza Tourist Zone as part of its efforts to tap into the tourism industry.

Conclusion

The Central Asian states have largely overcome the many pressing economic challenges following their independence in 1991 – albeit at their own pace and with varying degrees of sustainable success as demonstrated by the growth, income and unemployment data provided above.

With strong forecasted growth rates outpacing many other emerging economies in the world, and with a young and robust population excited about the global era of innovation, the region remains well-poised to attract global attention and investments.

To realize their full potential, the Central Asian countries should continue to focus on creating productive employment for their youth, revising their economies to achieve sustainable development goals, and diversify away from traditional sectors towards higher value-added industries. It is an exciting time for a region that holds the promise of ultimately achieving a safer and greener world.