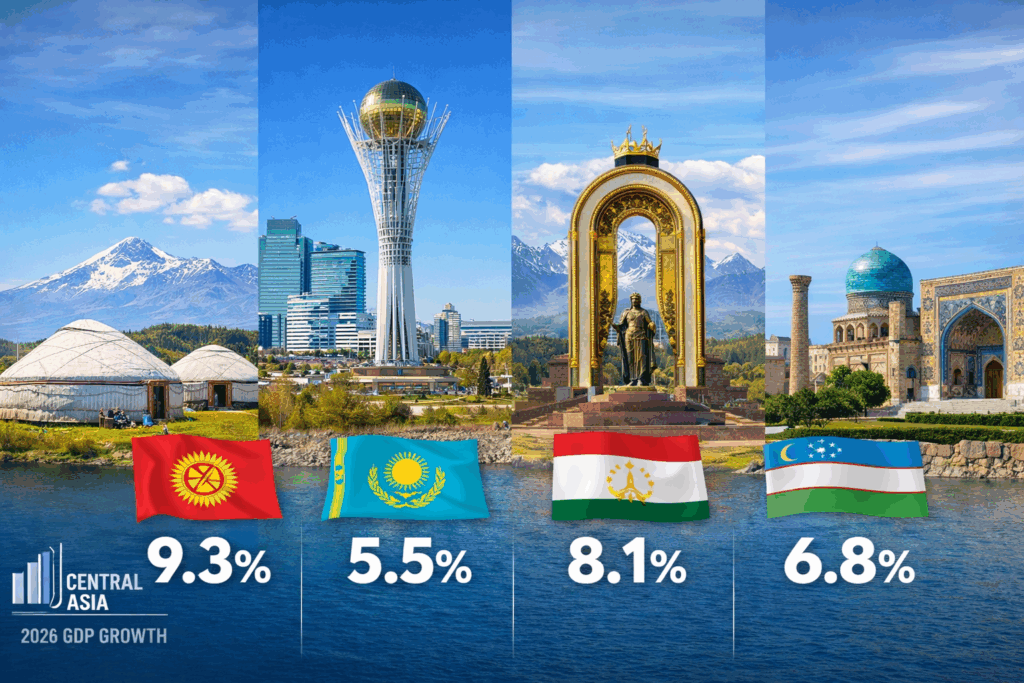

EDB Forecasts Strong Economic Growth in 2026 for Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

On December 18, the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB) published its Macroeconomic Outlook for 2026-2028, reviewing recent economic developments and offering projections for its seven member states: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. According to the report, aggregate GDP growth across the EDB region is forecast to reach 2.3% in 2026. Kyrgyzstan (9.3%), Tajikistan (8.1%), Uzbekistan (6.8%), and Kazakhstan (5.5%) are expected to remain the region’s fastest-growing economies. After two years of rapid expansion, the region’s GDP growth is set to moderate to 1.9% in 2025, down from 4.5% in 2024, mainly due to a slowdown in Russia’s economy. Although lower oil prices are expected to reduce export revenues for energy exporters such as Kazakhstan and Russia, the impact on overall growth will be limited. Meanwhile, net oil importers, including Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, will benefit from improved terms of trade and reduced inflationary pressure. High global gold prices will support foreign exchange earnings for key regional exporters, including Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The report also notes a gradual decline in the U.S. dollar’s share in central bank reserves across the region, though its role in international settlements remains stable. Kazakhstan Kazakhstan’s economy is projected to grow by 5.5% in 2026, supported by the implementation of the National Infrastructure Plan and the state program “Order for Investment,” which are expected to cushion the effects of lower oil prices. Growth in non-commodity exports will also play a stabilizing role. Inflation is forecast to decline to 9.7% by the end of 2026, after peaking early in the year due to a value-added tax (VAT) increase. The average tenge exchange rate is expected to be KZT 535 per U.S. dollar, underpinned by a high base interest rate and rising export revenues. Kyrgyzstan Kyrgyzstan is forecast to lead the region in GDP growth at 9.3% in 2026, driven by higher investment in transport, energy, water infrastructure, and housing construction. Inflation is expected to ease to 8.3%, although further declines will be constrained by higher tariffs and excise taxes. The average exchange rate is projected at KGS 89.2 per U.S. dollar, supported by robust remittance inflows and high global gold prices, gold being the country’s main export commodity. Tajikistan Tajikistan is projected to maintain high GDP growth of 8.1% in 2026, fueled by capacity expansion in the energy and manufacturing sectors, along with rising prices for gold and non-ferrous metals. Inflation is expected to reach 4.5% by year-end. The somoni is expected to remain stable, with an average exchange rate of TJS 9.8 per U.S. dollar, supported by growth in exports and remittances. Uzbekistan Uzbekistan’s economy is forecast to expand by 6.8% in 2026, sustained by strong investment activity and favorable gold prices. Inflation is projected to decline to 6.7%, helped by tight monetary policy and a stable exchange rate. The average soum exchange rate is expected to be UZS 12,800 per U.S. dollar, supported by high remittances and increased metal exports.

Pannier and Hillard’s Spotlight on Central Asia: New Episode Available Now

As Managing Editor of The Times of Central Asia, I’m delighted that, in partnership with the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, from October 19, we are the home of the Spotlight on Central Asia podcast. Chaired by seasoned broadcasters Bruce Pannier of RFE/RL’s long-running Majlis podcast and Michael Hillard of The Red Line, each fortnightly instalment will take you on a deep dive into the latest news, developments, security issues, and social trends across an increasingly pivotal region. This week, we're unpacking Turkmenistan's Neutrality Summit, a rare moment where a string of big names quietly rolled into Ashgabat, and where the public messaging mattered just as much as the backroom deals. We'll also cut through the noise on the latest reporting from the Tajik–Afghan border, where misinformation is colliding with real security developments on the ground. From there, we'll take a hard look at the results of Kyrgyzstan's elections, what they actually tell us about where Bishkek is heading next, and what they don't, before examining the looming power rationing now shaping daily life and political pressure in two Central Asian states. And to wrap it up, we're joined by two outstanding experts for a frank conversation on gendered violence in Central Asia: what's changing, what isn't, and why the official statistics may only capture a fraction of the reality. On the show this week: Daryana Gryaznova (Equality Now) Svetlana Dzardanova (Human Rights and Corruption Researcher)

Japan Steps Out of the Shadows With First Central Asia Leaders’ Summit

On December 19-20, Tokyo will host a landmark summit poised to reshape Eurasian cooperation. For the first time in the 20-year history of the “Central Asia + Japan” format, the dialogue is being elevated to the level of heads of state. For Japan, this represents more than a diplomatic gesture; it signals a shift from what analysts often describe as cautious “silk diplomacy” to a more substantive political and economic partnership with a region increasingly central to global competition over resources and trade routes. The summit will be chaired by Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi. The leaders of all five Central Asian states, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, have confirmed their participation. Alongside the plenary session, bilateral meetings and a parallel business forum are scheduled to take place. Why Now? Established in 2004, the “Central Asia + Japan” format has largely functioned as a platform for foreign ministers and technical cooperation. According to Esbul Sartayev, assistant professor at the Center for Global Risks at Nagasaki University, raising the dialogue to the head-of-state level marks a deliberate step by Japan to abandon its traditionally “secondary” role in a region historically dominated by Russia and China. This shift comes amid a changing geopolitical context: disrupted global supply chains, intensifying competition for critical and rare earth resources, and a growing U.S. and EU presence in Central Asia. In this environment, Tokyo is promoting a coordinated approach to global order “based on the rule of law”, a neutral-sounding phrase with clear geopolitical resonance. Unlike other external actors in Central Asia, Japan has historically emphasized long-term development financing, technology transfer, and institutional capacity-building rather than security alliances or resource extraction. Japanese engagement has focused on infrastructure quality, human capital, and governance standards, allowing Tokyo to position itself as a complementary partner rather than a rival power in the region. Economy, Logistics, and AI The summit agenda encompasses a range of priorities: sustainable development, trade and investment expansion, infrastructure and logistics, and digital technology. Notably, the summit is expected to include a new framework for artificial intelligence cooperation aimed at strengthening economic security and supply chain development. It is also likely to reference expanded infrastructure cooperation, including transport routes linking Central Asia to Europe. As a resource-dependent country, Japan sees Central Asia as part of its evolving “resource and technological realism” strategy. For the Central Asian states, this presents a chance to integrate into new global value chains without being relegated to the role of raw material suppliers. Kazakhstan: Deals Worth Billions The summit coincides with Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s official visit to Japan from December 18-20. During the visit, more than 40 agreements totaling over $3.7 billion are expected to be signed. These span energy, renewables, digitalization, mining, and transport. Participants include Samruk-Kazyna, KEGOC, Kazatomprom, KTZ, and major Japanese corporations such as Marubeni, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Toshiba, and JOGMEC. Japan’s ambassador to Kazakhstan, Yasumasa Iijima, has referred to Kazakhstan as a future Eurasian transport and logistics hub, highlighting its strategic role in developing the Trans-Caspian route and the Middle Corridor. Uzbekistan and the Wider Regional Stake In the past decade, Uzbekistan has significantly deepened its economic ties with Japan. Between 2017 and 2024, bilateral trade increased 2.3 times to $388.6 million, with a 64% surge recorded in 2024 alone. There are now 121 Japanese capital companies operating in the country, with cumulative Japanese investment and loans over this period reaching $184 million. Key areas of future cooperation include green transformation, digitalization, and human capital development. Kyrgyzstan views the C5+1 format as a tool to enhance its diplomatic leverage through regional solidarity. Its priorities include renewable energy, ecology, sustainable tourism, and educational exchanges. Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, meanwhile, are primarily interested in Japanese investment and technology in the energy sector. Geoeconomics Without Confrontation Although the summit is civilian in nature, its agenda also touches on security, ranging from stability in Afghanistan to climate and water-related risks. Analysts note that Japan is offering a model of engagement that avoids coercive political demands or military ambitions, instead emphasizing institutional partnerships, technological cooperation, and human resource development, an approach which has been described as "trust-building diplomacy.” More broadly, the Central Asia + Japan format enhances Central Asia’s agency, allowing the region to present a unified voice and reduce dependency on asymmetric relationships with great powers. For Tokyo, it is an opportunity to carve out a stable, long-term role in a region where geoeconomics increasingly outweighs geopolitics. For Central Asian governments, the shift to a leaders-level summit strengthens their collective bargaining position by reinforcing the region’s ability to engage external partners as a bloc. Speaking jointly allows the five states to elevate shared priorities such as transport connectivity, energy transition, and technology access, while limiting the risks of being drawn into bilateral dependencies with larger powers.

The Digital Future of Central Asia: Who Is Shaping It, and How?

Digital security is now a key component of most processes in every country. A large share of organizations is moving, or has already moved, their processes online, which requires increased attention and control. Many Central Asian countries are already rolling out AI technologies at the state level. Financial institutions, social systems, crypto services, rental services, and other high-risk areas can no longer develop effectively without biometric identification and AI. Central Asia is gradually developing its own biometric landscape, and if we look at it not as a set of disparate projects but as an emerging infrastructure, it becomes clear that the countries are moving at very different speeds.

Kazakhstan: Leader in Biometrics and Digital Identity in the Region

Today, Kazakhstan is the undisputed leader in Central Asia in the field of biometric technologies. In this region biometrics has long gone beyond isolated pilots and has become part of the digital infrastructure on which a significant part of the economy operates. Unlike neighboring countries, where biometrics is most often limited to video surveillance or exclusively state initiatives, Kazakhstan has developed a mature market of independent developers and technology companies creating competitive products both for private organizations and for government platforms. Thanks to active digitalization, biometrics in the country has become not an add-on, but the primary mechanism for identity verification. The state additionally stimulates this process: it expands the use of biometric identification in ministerial processes, strengthens the requirements for remote verification, and transfers critical services, such as the issuance of an Electronic Digital Signature (EDS), to biometric authentication. In this way, an environment is being built in which online processes gain full legal validity and the population receives convenient access to services without the need to visit physical offices. Kazakhstan’s key distinction is that it has a full-fledged biometrics market, not just government-driven initiatives. The private sector actively invests in biometric solutions, integrates them into its processes, and competes on the quality of the user experience. Banks strive to reduce entry barriers for clients, MFIs (software development kits) increase protection against fraud, crypto exchanges strengthen their compliance structure, and marketplaces implement biometric identification to secure transactions. This has created an effect unique for the region: biometrics has ceased to be a one-off project and has turned into an everyday part of business. Against this background, independent local companies are developing that are capable of creating advanced technological solutions within the country. Among them, Biometric.Vision stands out in particular, an international company originating from Kazakhstan, one of the key players in the Kazakhstani market that has formed its own technological stack and operates across several industries. The company has become a technological partner for banks, financial organizations, government services, and regulated industries, providing software modules for remote identification, biometric verification, liveness checks, and fraud prevention. Local products make it possible to respond quickly to new regulatory requirements, adapt to them, and address the real needs of local businesses. For Kazakhstan, the presence of local players in the biometrics market is an important strategic advantage, since many Central Asian countries are dependent on external providers. In this region biometrics has become not just a local product, but a full-fledged element of digital sovereignty, thanks to which the country can control high-risk identity infrastructure without relying on external providers. Therefore, biometrics in Kazakhstan has become not just a technological tool, but the foundation of trust between the state, business, and citizens. The presence of independent developers, mature demand from businesses, and active state support is turning the country into the most dynamically developing biometrics market in the region, and it is here that the model is being formed which other Central Asian countries will adopt in the coming years.Kyrgyzstan: State-Led Development of Biometric Systems

By contrast, neighboring Kyrgyzstan looks very different. While in Kazakhstan biometrics has long since also become a private business tool, in Kyrgyzstan it remains primarily an element of state security systems and document management. The most advanced area here is biometric passports, which have provided enhanced security compared to the ordinary ones since 2021. Such passports comply with ICAO international protection standards. This is a significant step forward that confirms the technological ambitions of the state, but the introduction of digitalization into the processes of private players is severely limited. Another notable segment is video surveillance and access control systems, where solutions with facial recognition are being actively implemented. However, all of this is essentially security infrastructure, not a digital identity ecosystem capable of serving such financial institutions as banks, MFIs, pawnshops, and, in general, any private business sectors and organizations. In Kyrgyzstan there are still no independent local companies that could offer a full-fledged e-KYC module, provide an SDK, API, a remote identification platform, and take on the legal validity of the process. The commercial biometrics market has in fact not been formed, and businesses that require remote customer identification either rely on external solutions or are forced to make do with simpler mechanisms. The development of biometric passports depended on the German company Mühlbauer and the American company Entrust. The state enterprise Infocom was only responsible for the overall coordination of the project. Private players are even more constrained and are forced to turn to imported solutions from India (Accurascan), which greatly complicates control over the process, adaptation to local regulatory requirements, and the overall development of local technologies in the region. In terms of the depth of technologies and integration with the digital economy, Kyrgyzstan is noticeably lagging behind Kazakhstan, although in terms of the level of implementation of video surveillance and government documents it is making significant strides, yet it still heavily depends on foreign players.Tajikistan: Biometrics Without a Market

Tajikistan is at an even earlier stage of development. Here biometrics appears in a fragmented way and mainly through external integrators that, as security measures, install video surveillance cameras, access terminals, or equipment from foreign manufacturers. The most active players in the market remain companies like Sarfaroz, which work with security systems, access control, and video surveillance, but do not develop solutions for remote identity verification. Tajikistan so far does not have a single independent local player capable of offering the market local e-KYC technologies, and the digital identification of citizens remains a domain dominated by the state. An example of this was the recent decision by the state to move retirees to digital identification. The State Agency for Social Protection has begun implementing mandatory registration through a mobile application, facial recognition, and photographing of documents. This is a major step in digitalization, affecting a large and vulnerable segment of the population. However, the implementation of this project once again highlights the specifics of the Tajik market: the technology contractor is not named, no private developer is visible, and all digital identification is precisely a state mechanism rather than a product created by an independent local company. In Tajikistan biometrics is developing from the top down, through government contracts and a narrowly focused security infrastructure, rather than through a private market of technological solutions. The absence of independent local e-KYC developers makes the market one-sided: all significant projects, from video surveillance systems to new mechanisms of digital identification of citizens, are tied to government agencies and integrators working with imported equipment. This limits the flexibility of implementations and slows down the pace of innovation. The country effectively remains in a situation where biometric technologies are applied only where they are initiated by the state, while the private sector has neither the tools nor the capabilities for the independent development of digital identity.The Future of Digital Identity in Central Asia

Central Asia is gradually entering a stage of digital transformation, where biometrics is becoming one of the key elements of the future socio-economic model. The field of digital identity is shaping a new level of interaction between the state, business, and citizens. Despite a noticeable difference in pace, the countries of the region are moving in the same direction, toward creating a sustainable and secure digital environment that will determine their competitiveness in the coming years. The future success of Central Asia in the field of digital identity will depend on the ability of the countries to build their own technological competencies, modernize the regulatory environment, and create conditions for the development of local innovative companies. If these factors align, the entire region will be able to move from being a consumer of technology to becoming a creator, forming a space in which biometrics will become not just a means of identification, but a platform for a new digital economy.Bishkek to Host Second B5+1 Forum of Central Asia and the U.S.

Kyrgyzstan is preparing to host the second B5+1 Forum of Central Asia and the United States, scheduled for February 4-5, 2026, in Bishkek. On December 12, Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Economy and Commerce held a joint briefing for ambassadors from Central Asian countries and the United States to outline preparations for the event. The B5+1 platform serves as the business counterpart to the C5+1 diplomatic initiative, which unites the five countries of Central Asia – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan – with the United States. Launched by the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) under its Improving the Business Environment in Central Asia (IBECA) program, B5+1 is supported by the U.S. Department of State and aims to foster high-level engagement between business leaders and policymakers. The upcoming forum in Bishkek builds on the outcomes of the C5+1 Summit held in Washington on November 6 this year. Its objective is to deepen U.S.-Central Asia economic cooperation and highlight the private sector’s pivotal role in advancing economic reform across the region. The event is co-hosted by CIPE and the Kyrgyz government. According to organizers, the forum’s agenda will focus on key sectors including agriculture, e-commerce, information technology, transport and logistics, tourism, banking, and critical minerals. These thematic areas reflect emerging regional priorities and shared interests in enhancing sustainable growth and economic resilience. The B5+1 Forum aims to create a platform for sustained dialogue between governments and private sector actors, encouraging the development of long-term partnerships and policy coordination. The inaugural B5+1 Forum was held in Almaty in March 2024, and brought together over 250 stakeholders from all five Central Asian countries and the United States. The first event centered on regional cooperation and connectivity, with a strong emphasis on empowering the private sector to support the objectives of the C5+1 Economic and Energy Corridors.

Nomad TV: Russia’s Latest Media Venture in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan has a new TV station. At first glance, it’s the kind of cozy, local news channel satirized in 2004’s Anchorman. The headline item on December 10th was the fact that it had snowed in Bishkek, with the on-screen reporter treading around the city asking residents whether they felt cold.

“Not really,” is the general response, given that plummeting temperatures are hardly a new phenomenon in the Kyrgyz capital.

“What kind of precautions did you take against the weather?” the reporter asks one gentleman.

“Put on a hat and gloves,” comes the droll reply.

This piece is followed by an interview with a representative of the city’s police service, advising people to tread carefully on the icy pavements.

Similar soft news items follow: an interview on the progress of Asman eco-city on Lake Issyk Kul; the modernization of a factory in Bishkek; and the announcement of a new coach for the national football team.

These are hardly stories to make waves. Indeed, most people in Bishkek are unaware of the new channel’s existence.

“It hasn't been a major discussion point; the only presence that I felt is this huge, green box that has been installed on the central square,” Nurbek Bekmurzaev, the Central Asian editor of Global Voices, told The Times of Central Asia, referring to the broadcaster’s temporary studio at the heart of the city.

Yet Nomad is one of the best-funded media outfits in the country, offering salaries twice as high as those paid by rival organizations. And, in one form or another, it seems clear that the money is coming from the Russian state.

So why has the Kremlin, which is hardly underrepresented in Kyrgyzstan’s media sphere, decided to throw such sums at a local news station?

[caption id="attachment_40853" align="aligncenter" width="1600"] Nomad TV’s temporary studio on Ala-Too square in the heart of Bishkek; image: TCA, Joe Luc Barnes[/caption]

A Bold Start

Nomad’s initial coverage was not so banal. On November 23, the channel began broadcasting with a cascade of high-profile interviews linked to Vladimir Putin’s state visit to Kyrgyzstan on November 25-27.

This followed a lavish launch ceremony at the city’s opera house, attended by Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, Maria Zakharova, and the Kyrgyz deputy Prime Minister Edil Baisalov. Putin himself lauded the new channel in his speech on November 26, and gave its chief editor, Natalia Korolevich, an exclusive interview the following day.

This followed a feverish autumn, which the broadcaster had spent poaching talent from newsrooms around Bishkek.

This included Mirbek Moldabekov, a veteran broadcaster from the state television channel, UTRK; the head of Sputnik in Kyrgyzstan, Erkin Alimbekov; and his wife, Svetlana Akmatalieva, a journalist from the National TV and Radio Corporation. The channel’s producer is Anna Abakumova, a former RT journalist who gained fame reporting from Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine.

These aggressive recruitment tactics have split the profession in Kyrgyzstan. Journalist Adil Turdukolov asserted in an interview with Exclusive.kz that anyone who has chosen to work for Nomad “is not particularly concerned with the moral or civic aspects [of the job].”

Others in the media industry told TCA under condition of anonymity that the campaign against journalists joining the new channel “has become a little hysterical.”

[caption id="attachment_40854" align="aligncenter" width="1600"]

Nomad TV’s temporary studio on Ala-Too square in the heart of Bishkek; image: TCA, Joe Luc Barnes[/caption]

A Bold Start

Nomad’s initial coverage was not so banal. On November 23, the channel began broadcasting with a cascade of high-profile interviews linked to Vladimir Putin’s state visit to Kyrgyzstan on November 25-27.

This followed a lavish launch ceremony at the city’s opera house, attended by Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, Maria Zakharova, and the Kyrgyz deputy Prime Minister Edil Baisalov. Putin himself lauded the new channel in his speech on November 26, and gave its chief editor, Natalia Korolevich, an exclusive interview the following day.

This followed a feverish autumn, which the broadcaster had spent poaching talent from newsrooms around Bishkek.

This included Mirbek Moldabekov, a veteran broadcaster from the state television channel, UTRK; the head of Sputnik in Kyrgyzstan, Erkin Alimbekov; and his wife, Svetlana Akmatalieva, a journalist from the National TV and Radio Corporation. The channel’s producer is Anna Abakumova, a former RT journalist who gained fame reporting from Russian-occupied territories in Ukraine.

These aggressive recruitment tactics have split the profession in Kyrgyzstan. Journalist Adil Turdukolov asserted in an interview with Exclusive.kz that anyone who has chosen to work for Nomad “is not particularly concerned with the moral or civic aspects [of the job].”

Others in the media industry told TCA under condition of anonymity that the campaign against journalists joining the new channel “has become a little hysterical.”

[caption id="attachment_40854" align="aligncenter" width="1600"] Vladimir Putin’s state visit to Kyrgyzstan on November 26, where he praised the launch of Nomad TV; image: TCA, Joe Luc Barnes[/caption]

A Warm Welcome

While Russia is hardly unique in having state media in Kyrgyzstan – Britain’s publicly-funded BBC operates a Kyrgyz service, while the United States Congress currently still funds Radio Azattyk (RFE/RL) – Rashid Gabdulhakov, associate professor at the University of Groningen, notes the contrasting reception that Nomad has received when compared to other foreign media.

“The claim that Nomad TV is ‘just another media outlet’ free to operate like any other is misleading,” he told TCA.

When Azattyk was defunded by the White House in March 2025, Kyrgyzstan’s President Sadyr Japarov responded favorably: “People do not need information from Azattyk… Trump and Musk’s decision should be supported,” he said, having accused the media outlet of disinformation.

Meanwhile, independent media in Kyrgyzstan, such as Kloop and Temirov Live, have been designated extremist organizations. “Former employees were prosecuted for having worked there,” said Gabdulhakov. “Even liking or sharing Kloop’s content can now carry risks.”

He contrasts that with the fact that leading politicians are eager to appear in interviews with Russia’s new channel.

“Nomad offers something politically convenient: predictable, Kremlin-aligned messaging that also flatters the ruling regime in Bishkek, as long as it stays within the boundaries acceptable to Moscow,” he said.

Russia’s Wider Media Ambitions

Russian television channels such as Channel One, Russia 24, Kultura, and Zvezda already broadcast in Kyrgyzstan, and coffee shops such as Vanilla Sky offer a free copy of the state newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta. So what purpose is being served by the creation of another channel?

Temur Umarov, research fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin, believes that money lies at the root of it. “I don’t think anyone in Russia is thinking about it strategically, except as a means of pitching it to decision makers; it’s much more about money,” he told TCA, asserting that the channel is a means of “washing out the resources that Russia has for the purposes of particular people in the media machine.”

Others suspect that it might be a means of restoring influence on social media. Channels funded by the Russian state were removed from YouTube in 2022.

Although Nomad is evidently linked to the Russian state, given its access to the Russian president and the number of employees linked to Kremlin media, its funding sources are grey, and it is officially designated a Kyrgyz-Russian joint project.

An investigation by Azattyk revealed Nomad’s links to the shadowy non-profit organization, Evrasia, funded by Moldovan oligarch Ilan Shor and chaired by Russian Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin. The organization, which opened a Russian Cultural Center in Bishkek just before Putin’s visit, has already been at the heart of a disinformation campaign in the 2024 elections in Moldova, and is said to be in charge of training the new recruits for Nomad TV.

The funding appears to be grey enough, however. The channel has not yet fallen foul of YouTube, where it has over 6,000 subscribers, while on its Instagram account, this figure has risen to more than 20,000. While these figures are modest, they may represent a test case in how to spread Russian influence abroad.

The use of these U.S. platforms is rather ironic given that Instagram has been designated as extremist by Moscow and is banned within Russia. Meanwhile, YouTube’s speed has been affected by Rozkomnadzor, the country’s internet censor, making its use difficult without a VPN.

Such hypocrisy is not unique to Russia, with Chinese state media also making use of YouTube to spread their own state narrative despite banning it at home – CGTN alone has 3.6 million subscribers. In this case, “influence strategy takes precedence over ideological consistency,” said Gabdulhakov.

Nomad’s launch in Kyrgyzstan was quickly followed by a larger Russian campaign elsewhere – on December 5, RT opened a new bureau in India, based in New Delhi.

Is there an audience?

While RT’s operation in New Delhi suggests the Kremlin sees scope for pushing its narrative in the global south, Nomad’s style is quite different. Unlike RT, there is little in the way of foreign wars, hordes of migrants, or sensationalist polemics. The thunderous, frenetic music is nowhere to be heard either.

For all the fanfare of the launch, the high-level interviews, and the glitzy studio, Nomad’s offerings have focused on the local and the everyday. When there is no news, the channel rebroadcasts NTV, another Russian state channel.

And there are further doubts about the potential audience. Although there is a Kyrgyz option on the channel, the main broadcasting language is Russian, and according to Bekmurzaev, “most people don't understand Russian well enough to listen to news and debates.”

That said, the channel’s Kyrgyz language Instagram page has seen far faster growth than its Russian equivalent, suggesting that social media may be the long-term play.

“TV is dead,” says Umarov bluntly. “Everyone is going from TV to socials.”

Umarov is also unconvinced about Moscow’s desire to influence the Kyrgyz population. “I would be surprised if it became an effective tool to spread the Kremlin’s message,” he said.

“The Kremlin thinks that the audience doesn’t really matter. As long as there is an understanding among the elites, the Kremlin is happy. It doesn’t really need the support of the population.”

Vladimir Putin’s state visit to Kyrgyzstan on November 26, where he praised the launch of Nomad TV; image: TCA, Joe Luc Barnes[/caption]

A Warm Welcome

While Russia is hardly unique in having state media in Kyrgyzstan – Britain’s publicly-funded BBC operates a Kyrgyz service, while the United States Congress currently still funds Radio Azattyk (RFE/RL) – Rashid Gabdulhakov, associate professor at the University of Groningen, notes the contrasting reception that Nomad has received when compared to other foreign media.

“The claim that Nomad TV is ‘just another media outlet’ free to operate like any other is misleading,” he told TCA.

When Azattyk was defunded by the White House in March 2025, Kyrgyzstan’s President Sadyr Japarov responded favorably: “People do not need information from Azattyk… Trump and Musk’s decision should be supported,” he said, having accused the media outlet of disinformation.

Meanwhile, independent media in Kyrgyzstan, such as Kloop and Temirov Live, have been designated extremist organizations. “Former employees were prosecuted for having worked there,” said Gabdulhakov. “Even liking or sharing Kloop’s content can now carry risks.”

He contrasts that with the fact that leading politicians are eager to appear in interviews with Russia’s new channel.

“Nomad offers something politically convenient: predictable, Kremlin-aligned messaging that also flatters the ruling regime in Bishkek, as long as it stays within the boundaries acceptable to Moscow,” he said.

Russia’s Wider Media Ambitions

Russian television channels such as Channel One, Russia 24, Kultura, and Zvezda already broadcast in Kyrgyzstan, and coffee shops such as Vanilla Sky offer a free copy of the state newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta. So what purpose is being served by the creation of another channel?

Temur Umarov, research fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin, believes that money lies at the root of it. “I don’t think anyone in Russia is thinking about it strategically, except as a means of pitching it to decision makers; it’s much more about money,” he told TCA, asserting that the channel is a means of “washing out the resources that Russia has for the purposes of particular people in the media machine.”

Others suspect that it might be a means of restoring influence on social media. Channels funded by the Russian state were removed from YouTube in 2022.

Although Nomad is evidently linked to the Russian state, given its access to the Russian president and the number of employees linked to Kremlin media, its funding sources are grey, and it is officially designated a Kyrgyz-Russian joint project.

An investigation by Azattyk revealed Nomad’s links to the shadowy non-profit organization, Evrasia, funded by Moldovan oligarch Ilan Shor and chaired by Russian Duma speaker Vyacheslav Volodin. The organization, which opened a Russian Cultural Center in Bishkek just before Putin’s visit, has already been at the heart of a disinformation campaign in the 2024 elections in Moldova, and is said to be in charge of training the new recruits for Nomad TV.

The funding appears to be grey enough, however. The channel has not yet fallen foul of YouTube, where it has over 6,000 subscribers, while on its Instagram account, this figure has risen to more than 20,000. While these figures are modest, they may represent a test case in how to spread Russian influence abroad.

The use of these U.S. platforms is rather ironic given that Instagram has been designated as extremist by Moscow and is banned within Russia. Meanwhile, YouTube’s speed has been affected by Rozkomnadzor, the country’s internet censor, making its use difficult without a VPN.

Such hypocrisy is not unique to Russia, with Chinese state media also making use of YouTube to spread their own state narrative despite banning it at home – CGTN alone has 3.6 million subscribers. In this case, “influence strategy takes precedence over ideological consistency,” said Gabdulhakov.

Nomad’s launch in Kyrgyzstan was quickly followed by a larger Russian campaign elsewhere – on December 5, RT opened a new bureau in India, based in New Delhi.

Is there an audience?

While RT’s operation in New Delhi suggests the Kremlin sees scope for pushing its narrative in the global south, Nomad’s style is quite different. Unlike RT, there is little in the way of foreign wars, hordes of migrants, or sensationalist polemics. The thunderous, frenetic music is nowhere to be heard either.

For all the fanfare of the launch, the high-level interviews, and the glitzy studio, Nomad’s offerings have focused on the local and the everyday. When there is no news, the channel rebroadcasts NTV, another Russian state channel.

And there are further doubts about the potential audience. Although there is a Kyrgyz option on the channel, the main broadcasting language is Russian, and according to Bekmurzaev, “most people don't understand Russian well enough to listen to news and debates.”

That said, the channel’s Kyrgyz language Instagram page has seen far faster growth than its Russian equivalent, suggesting that social media may be the long-term play.

“TV is dead,” says Umarov bluntly. “Everyone is going from TV to socials.”

Umarov is also unconvinced about Moscow’s desire to influence the Kyrgyz population. “I would be surprised if it became an effective tool to spread the Kremlin’s message,” he said.

“The Kremlin thinks that the audience doesn’t really matter. As long as there is an understanding among the elites, the Kremlin is happy. It doesn’t really need the support of the population.”

The Silk Visa Deadlock: The Long Road to a Borderless Central Asia

The year 2025 will likely be remembered as a milestone in Central Asian diplomacy. Regional leaders signed landmark agreements on water and energy cooperation and launched major investment projects. At high-level meetings, Central Asian presidents emphasized a new phase of deeper cooperation and greater unity, highlighting strategic partnership and shared development goals. But at ground level, at border crossings such as Korday between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, or the congested diversion routes replacing the closed Zhibek Zholy checkpoint, the picture is far less seamless. Long queues, heightened scrutiny, and bureaucratic delays remain the norm. While political rhetoric celebrates unity, the reality on the ground tells a different story. The region’s physical borders remain tightly controlled. A key symbol of unrealized integration is the stalled “Silk Visa” project, a proposed Central Asian version of the Schengen visa that would allow tourists to travel freely across the region. The project has made little headway, with experts suggesting that, beyond technical issues, deeper concerns, including economic disparities and security sensitivities, have played a role. Silk Visa: A Stalled Vision Launched in 2018 by Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, the Silk Visa was envisioned as a game-changer for regional tourism and mobility. Under the scheme, tourists with a visa to one participating country could move freely across Central Asia, from Almaty to Samarkand and Bishkek. Seven years on, the project has yet to materialize. Official explanations point to the difficulty of integrating databases on “undesirable persons.” But as Uzbekistan’s Deputy Prime Minister acknowledged earlier this year, the delay stems from the need to harmonize security services and create a unified system. Experts also cite diverging visa policies and resistance from national security agencies unwilling to share sensitive data. As long as each country insists on determining independently whom to admit or blacklist, the Silk Visa will remain more aspiration than policy. Economic Imbalance: The Silent Barrier The most significant, albeit rarely acknowledged, hurdle to regional openness is economic inequality. Kazakhstan’s GDP per capita, at over $14,000, is significantly higher than that of Uzbekistan or Kyrgyzstan, which hover around $2,500-3,000. This disparity feeds fears in Astana that full border liberalization would trigger a wave of low-skilled labor migration, putting strain on Kazakhstan’s urban infrastructure and labor market. While Kazakhstan is eager to export goods, services, and capital across Central Asia, it remains reluctant to import unemployment or social tension. Migration pressure is already high: according to Uzbekistan’s Migration Agency, the number of Uzbek workers in Kazakhstan reached 322,700 in early 2025. Removing border controls entirely could exacerbate this trend, overwhelming already stretched public services. Security Concerns and Regional Tensions The geopolitical landscape further complicates the dream of borderless travel. A truly open regional system would require a strong, unified external border, something unattainable given Afghanistan’s proximity. The persistent threats of drug trafficking and extremist infiltration compel Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to maintain tight border controls. Kazakhstan, while geographically removed, remains cautious about loosening controls along its southern frontier. Moreover, despite recent agreements on delimiting the Kyrgyz–Tajik border, tensions in the area remain unresolved, underscoring the fragility of regional trust, making the creation of a unified security space across all five countries a distant prospect. The war in Ukraine has further complicated the region’s geopolitical calculus. Russia remains Central Asia’s primary destination for its migrant labor, but the conflict has strained Moscow’s economic capacity and pushed regional governments to diversify partnerships. This uncertainty reinforces risk-averse security policies, making leaders even less willing to consider fully open borders. Reality Check: Trade Over Tourism Perhaps the most tangible measure of regional integration is logistics. Yet even this is underwhelming. The Korday (Ak Zhol) crossing remains a choke point for trade between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Despite digital queueing systems, businesses continue to report delays, and truck drivers face multi-day traffic jams. These recurring trade bottlenecks indicate that borders are still used as tools of economic leverage, undermining promises of seamless transit. Considering all factors, the emergence of a full-fledged 'Central Asian Schengen' in the foreseeable future appears unlikely. The combination of security risks and economic imbalance makes open borders politically unpalatable. Instead, the region may follow a model akin to “Two-speed Europe,” with elite-driven economic integration, such as simplified cargo transit and digital customs systems, advancing faster than broader public mobility. For most citizens, however, the dream of borderless Central Asia will remain just that: a dream.

Kyrgyzstan’s Creative Industries Park: Inside the Country’s Latest Artistic “Miracle”

Kyrgyz cinema in the 1960s to 1970s was sometimes referred to as the ‘Kyrgyz Miracle’, for the number of great pieces that were made during this time. This is still symbolic today, as the country is now in another ‘miracle’ era for the creative industries, which is setting an example not just for the Central Asia region, but globally. In 2023 Daniyar Amanaliev, Co-Founder of an art studio named ololo and Chairman of the Supervisory Board of the Creative Industries Park, told Deutsche Welle: “We have a very small country. When you start a business here, it's very difficult to start making money because the market is so small. And our innovators are people who are involved in creative businesses. Almost all of these companies have intangible products that cannot be stopped at customs or sealed in a warehouse. Everything is in people's heads, on computers, in the cloud, and this is exactly the kind of business model that can thrive in the Kyrgyz Republic”. This story starts with Ololo, a small art studio in Bishkek founded in 2016 by Daniar Amanaliev, Ainura Amanalieva, Atai Sadybakasov, and Victoria Yurtaeva. The initial idea was to change the lifestyle of Kyrgyz citizens, enriching their lives with different forms of art, and let them pursue the dreams of their youth. The studio provided a wide range of art classes with no age restrictions. The company soon switched its business model to operating creative hubs. Yurtaeva soon left the project. Fast forward nine years and in 2025 Ololo is the largest chain of creative hubs in Central Asia, with nine locations in Kyrgyzstan and an upcoming launch of their tenth location in Kazakhstan. In October 2021 Ololo was crucial to the launch of the Association of Creative Industries of the Kyrgyz Republic, together with eight other companies from the creative industries. Starting as a modest group, the association is now among the most active associations in the country, with over 50 member companies representing over 20 creative industries. In April 2022 the country’s President Sadyr Japarov signed an Order on the development of the creative industries. He even visited the very first Create4 creative industries festival later that year. Kyrgyzstan’s Creative Industries Park (CIP) came into being in summer 2022. Almost a year later, the relevant amendments to the national Tax Code were approved. In June 2023 a government order regulating the operations of the Creative Industries Park was adopted. And, finally, the register of industries exempt from taxes under the Creative Industries Park were defined in December of 2023.

The World’s First

Now the Creative Industries Park is the very first model globally for boosting creative industries in this way, which is a viable case for other countries to follow. Amanaliev is the only member from Central Asia in the Global Creative Economy Council, part of the UK’s Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre. His counterparts from different parts of the world are now carefully watching how this new model unfolds. It has been quite successful so far, and is only gaining momentum. CIP provides a special tax regime for companies operating in the creative industries, offering significantly reduced tax rates. At the moment 72 creative sectors, from cinema and music to fashion and graphic arts, enjoy the benefits of the park. The Park has over 130 members already, which made over KGS 500 million (~$6 million) in revenue in Q3 2025, a more than ten-fold growth since Q3 2024. A similar special tax regime for IT outsourcing, the High Technology Park, saw a 500x growth in the revenue of its residents in its first decade from its launch in 2013 to 2023. CIP has all the potential to grow even further. In 2025 CIP launched its own Creative Industries Support Fund, which runs its grant program and started financially supporting promising initiatives, projects, and startups in the creative industries. Last month CIP held its very first contest for companies operating in the creative industries, where participants could win equity-free cash prizes to further develop their companies. Speaking about the potential for his project, Amanaliev told The Times of Central Asia: “A Creative Industries Park is a good idea for any country in the Global South. I’m sure, in the nearest 5-10 years we will witness the adaptation of this idea in many places. It will become a great contribution of the Kyrgyz Republic to the development of the creative economy in the world!”Sunkar Podcast

Central Asia and the Troubled Southern Route