Pannier and Hillard’s Spotlight on Central Asia: New Episode Out Now

As Managing Editor of The Times of Central Asia, I’m delighted that, in partnership with the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, from October 19, we are the home of the Spotlight on Central Asia podcast. Chaired by seasoned broadcasters Bruce Pannier of RFE/RL’s long-running Majlis podcast and Michael Hillard of The Red Line, each fortnightly instalment will take you on a deep dive into the latest news, developments, security issues, and social trends across an increasingly pivotal region. This week, the team will be covering Kazakhstan announcing the date for its upcoming constitutional referendum, controversial polling decisions in Kazakhstan, a new fighting force forming that could make the Tajikistan–Afghanistan border even more volatile, one leader returning from an unexplained absence, and several others travelling to the United States for talks that are raising eyebrows. We'll also cover a major government reshuffle in Turkmenistan, before turning to our main story: the removal of one of Kyrgyzstan's most powerful figures, and the political and geopolitical aftershocks likely to follow. On the show this week: - Emil Dzhuraev (Political Expert)

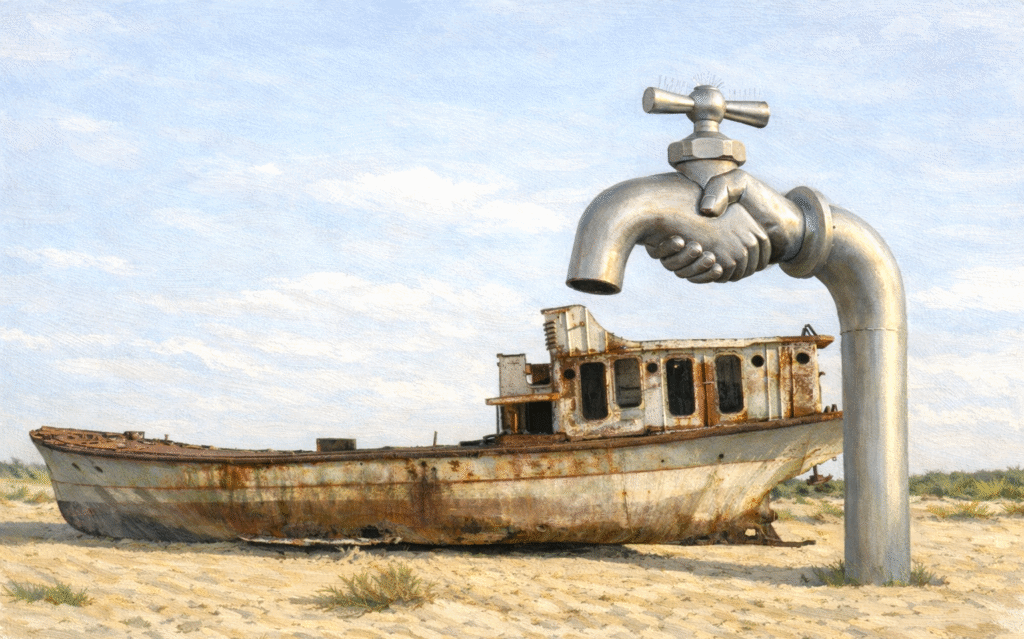

Central Asia and the Global Water Crisis: A Test of Governance and Cooperation

Water scarcity is rapidly transforming from a regional environmental concern into one of the defining global security challenges of the 21st century. UN-linked assessments estimate that around four billion people experience severe water scarcity for at least one month each year, and nearly three-quarters of the global population lives in countries facing water insecurity.

Against this backdrop, Central Asia is not an exception but rather a concentrated example of global dynamics: climate pressure, population growth, and inefficient resource management. Regional initiatives, including proposals put forward by Kazakhstan, therefore have the potential to contribute not only to stability in Central Asia but to the development of a more coherent global water governance architecture.

The Water Crisis as a Global Reality

Water is increasingly regarded as a strategic resource on par with energy and food. Climate change is intensifying droughts, floods, and the degradation of aquatic ecosystems across all regions, from Africa and the Middle East to South Asia, Europe, and North America.

Recent mapping and analysis by investigative groups and international media indicate that half of the world’s 100 largest cities experience high levels of water stress, with dozens classified as facing extremely high levels. Major urban centers, including Beijing, New York, Los Angeles, Rio de Janeiro, and Delhi, are among those under acute pressure, while cities such as London, Bangkok, and Jakarta are also categorized as highly stressed.

In this context, Central Asia is not an outlier. It is confronting today what may soon become the global norm.

Central Asia: Where Global Trends Converge

A defining feature of the current environmental situation is that factors beyond natural ones drive the water crisis. Experts increasingly stress that shortages are often less about absolute physical scarcity and more about outdated management systems, infrastructure losses, and inefficient consumption patterns. In this respect, Central Asia can be seen as a testing ground for global water challenges, where multiple stress factors converge.

The region, with mountain peaks exceeding 7,000 meters, contains some of the largest ice reserves outside the polar regions. The Pamir and Hindu Kush ranges, together with the Tibetan Plateau, the Himalayas, and the Tien Shan, form part of what is sometimes referred to as the “Third Pole,” the largest concentration of ice after the Arctic and Antarctic.

[caption id="attachment_13410" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] The White Horse Pass, Tajikistan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

However, the pace of change is alarming. By 2030-2040, water scarcity in Central Asia risks becoming chronic. Glaciers in the Western Tien Shan, for example, have reportedly shrunk by roughly 27% over the past two decades and continue to retreat, posing a direct threat to the flow of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. These rivers increasingly fail to reach the Aral Sea in sufficient volume, while the exposed seabed has become a major source of salt and dust storms.

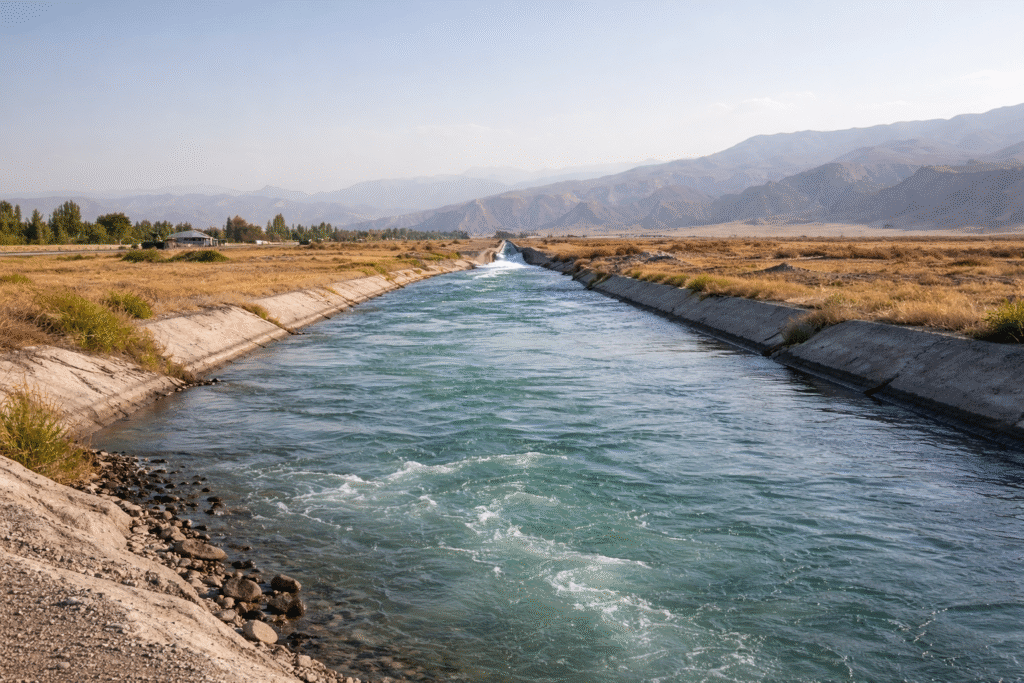

[caption id="attachment_21928" align="aligncenter" width="2560"]

The White Horse Pass, Tajikistan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

However, the pace of change is alarming. By 2030-2040, water scarcity in Central Asia risks becoming chronic. Glaciers in the Western Tien Shan, for example, have reportedly shrunk by roughly 27% over the past two decades and continue to retreat, posing a direct threat to the flow of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. These rivers increasingly fail to reach the Aral Sea in sufficient volume, while the exposed seabed has become a major source of salt and dust storms.

[caption id="attachment_21928" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Moynaq, Karakalpakstan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

Infrastructure inefficiencies compound the problem. Estimates suggest that in some systems, 40-50% of water can be lost in deteriorating canals and distribution networks before reaching end users. Agriculture accounts for approximately 80-90% of total water withdrawals, much of it directed toward water-intensive crops cultivated using outdated irrigation techniques. Meanwhile, the region’s population could grow by almost 25% by 2040 compared with current levels, placing additional pressure on drinking water supplies and public utilities.

Taken together, these factors make water scarcity not only an environmental and economic issue but also a potential source of social instability. In this context, water is gradually becoming a matter of domestic and regional security rather than solely a question of resource management.

The challenge of water security, particularly the use of transboundary rivers, lakes, and seas, as well as climate-related impacts on aquatic systems, has long transcended national borders. In Central Asia, this is reflected in asymmetries between upstream and downstream states. Globally, it manifests in growing tensions between regions with relative water abundance and those facing chronic deficits.

The United Nations has repeatedly warned that, under conditions of accelerating climate change, water could become a significant trigger of conflict in the 21st century. Developing global rules, monitoring systems, and early-warning mechanisms is therefore becoming as important as implementing national conservation programs.

Technology and Management: Unlocking Hidden Reserves

International experience demonstrates that a substantial share of water deficits can be mitigated through improved governance and technology. Properly designed and maintained drip irrigation systems can reduce water use by 30-50% compared with traditional surface irrigation while supporting higher yields and improved crop quality.

Laser land leveling can cut irrigation water use by 25-30% without reducing yields. It enhances water efficiency, reduces weed growth, and promotes more uniform crop maturation, while also lowering the volume of water required for field preparation.

Replacing open earthen canals with pipeline systems can significantly reduce conveyance losses. Digital water metering, sensors, satellite monitoring, and information technologies help transform water from an “invisible” input into a measurable and manageable asset. In urban settings, water meters, efficient plumbing fixtures, and the reuse of treated wastewater provide additional savings.

Across regions, experts reach a similar conclusion: the crisis stems less from climate conditions alone and more from outdated management models. Modernizing governance and infrastructure often delivers the most immediate and substantial gains.

Regional Cooperation as Part of the Global Response

For Central Asia, a central priority is shifting from competition to cooperation. Proposals such as the creation of an International Water and Energy Consortium for the region reflect efforts to reconcile upstream and downstream interests, integrate water and energy considerations, and reduce the risk of conflict.

In late 2025, the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia reached agreement on water allocations from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers for the 2025–26 non-growing season — setting specific quotas for each state and ensuring a minimum flow through key hydrological points and the Aral Sea delta — underscoring that shared management is an operational reality as well as a strategic imperative

The importance of such mechanisms extends beyond the region. They illustrate how transboundary resources can be governed through shared rules, transparent data, and mutual benefit, elements that remain underdeveloped in the global water management system.

In this context, the initiative proposed by Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to establish an International Water Organization within the United Nations framework carries broader significance. It represents not merely a regional proposal but an attempt to strengthen institutional foundations for global water governance.

Over the long term, such an organization could serve as a platform for developing universal principles of water management, facilitating data exchange and scientific cooperation, providing early warnings of emerging crises, and preventing transboundary disputes over allocation.

As water-related risks increasingly affect countries across continents, initiatives of this kind align with wider efforts to adapt to climate change and enhance resilience.

Central Asia as an Early Indicator of a Global Shift

Central Asia is not on the periphery of the global water crisis; it is an early indicator of broader trends. Developments in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya basins may foreshadow similar challenges elsewhere.

Water scarcity represents a global governance challenge affecting Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and advanced economies alike. The region, therefore, has the potential to act not only as a zone of risk but also as a source of practical solutions. If water diplomacy, technological innovation, and institutional reform can succeed here, their lessons may prove applicable worldwide.

Water has become a test of the capacity of states and international institutions to act strategically. The sustainability of global development in the 21st century will depend in part on how that test is met.

Moynaq, Karakalpakstan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

Infrastructure inefficiencies compound the problem. Estimates suggest that in some systems, 40-50% of water can be lost in deteriorating canals and distribution networks before reaching end users. Agriculture accounts for approximately 80-90% of total water withdrawals, much of it directed toward water-intensive crops cultivated using outdated irrigation techniques. Meanwhile, the region’s population could grow by almost 25% by 2040 compared with current levels, placing additional pressure on drinking water supplies and public utilities.

Taken together, these factors make water scarcity not only an environmental and economic issue but also a potential source of social instability. In this context, water is gradually becoming a matter of domestic and regional security rather than solely a question of resource management.

The challenge of water security, particularly the use of transboundary rivers, lakes, and seas, as well as climate-related impacts on aquatic systems, has long transcended national borders. In Central Asia, this is reflected in asymmetries between upstream and downstream states. Globally, it manifests in growing tensions between regions with relative water abundance and those facing chronic deficits.

The United Nations has repeatedly warned that, under conditions of accelerating climate change, water could become a significant trigger of conflict in the 21st century. Developing global rules, monitoring systems, and early-warning mechanisms is therefore becoming as important as implementing national conservation programs.

Technology and Management: Unlocking Hidden Reserves

International experience demonstrates that a substantial share of water deficits can be mitigated through improved governance and technology. Properly designed and maintained drip irrigation systems can reduce water use by 30-50% compared with traditional surface irrigation while supporting higher yields and improved crop quality.

Laser land leveling can cut irrigation water use by 25-30% without reducing yields. It enhances water efficiency, reduces weed growth, and promotes more uniform crop maturation, while also lowering the volume of water required for field preparation.

Replacing open earthen canals with pipeline systems can significantly reduce conveyance losses. Digital water metering, sensors, satellite monitoring, and information technologies help transform water from an “invisible” input into a measurable and manageable asset. In urban settings, water meters, efficient plumbing fixtures, and the reuse of treated wastewater provide additional savings.

Across regions, experts reach a similar conclusion: the crisis stems less from climate conditions alone and more from outdated management models. Modernizing governance and infrastructure often delivers the most immediate and substantial gains.

Regional Cooperation as Part of the Global Response

For Central Asia, a central priority is shifting from competition to cooperation. Proposals such as the creation of an International Water and Energy Consortium for the region reflect efforts to reconcile upstream and downstream interests, integrate water and energy considerations, and reduce the risk of conflict.

In late 2025, the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia reached agreement on water allocations from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers for the 2025–26 non-growing season — setting specific quotas for each state and ensuring a minimum flow through key hydrological points and the Aral Sea delta — underscoring that shared management is an operational reality as well as a strategic imperative

The importance of such mechanisms extends beyond the region. They illustrate how transboundary resources can be governed through shared rules, transparent data, and mutual benefit, elements that remain underdeveloped in the global water management system.

In this context, the initiative proposed by Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to establish an International Water Organization within the United Nations framework carries broader significance. It represents not merely a regional proposal but an attempt to strengthen institutional foundations for global water governance.

Over the long term, such an organization could serve as a platform for developing universal principles of water management, facilitating data exchange and scientific cooperation, providing early warnings of emerging crises, and preventing transboundary disputes over allocation.

As water-related risks increasingly affect countries across continents, initiatives of this kind align with wider efforts to adapt to climate change and enhance resilience.

Central Asia as an Early Indicator of a Global Shift

Central Asia is not on the periphery of the global water crisis; it is an early indicator of broader trends. Developments in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya basins may foreshadow similar challenges elsewhere.

Water scarcity represents a global governance challenge affecting Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and advanced economies alike. The region, therefore, has the potential to act not only as a zone of risk but also as a source of practical solutions. If water diplomacy, technological innovation, and institutional reform can succeed here, their lessons may prove applicable worldwide.

Water has become a test of the capacity of states and international institutions to act strategically. The sustainability of global development in the 21st century will depend in part on how that test is met.

The Language Nobody Wants to Speak About: Russian’s Uneasy Place in Central Asia’s Cultural Conversation

Rhetoric in segments of the Russian media has sharpened debates over sovereignty and influence across Central Asia, pushing these concerns beyond policy circles and into everyday conversations. The region is reassessing not only pipelines and alliances, but language itself. In politics, this shift is visible and symbolic. In culture, it is more difficult to discern. The Russian language still shapes how Central Asian art is funded, circulated, and institutionally processed, even as institutions distance themselves from Moscow’s influence. This contradiction sits at the heart of contemporary cultural life in the region. Artists produce work rooted in Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tajik, or Turkmen histories. They title exhibitions in local languages. They speak passionately about decolonial futures and cultural sovereignty. But when the catalogue is written, the grant application submitted, or the curatorial text sent abroad, the language quietly shifts. First to Russian, sometimes to English, and only occasionally does it remain in the local language. This is not nostalgia, but a structural inheritance. Russian remains the shared professional language of much of the urban cultural sector. Edward Lemon, President of the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, argues that the language’s endurance reflects both ideology and pragmatism. “While local languages have become much more widespread as the Central Asian republics have strengthened their nationhood and as there has been an increase in anti-Russian sentiments since the invasion of Ukraine, Russian language use remains widespread,” Lemon told TCA. “Despite the ideological imperative to reduce reliance on Russian, there are some pragmatic reasons why it remains prominent. High levels of migration to Russia, particularly from Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan, mean that a basic competence in the language is essential to survival for many Central Asians. Russian remains a language of interethnic communication, particularly in Kazakhstan, where ethnic Russians, for the most part, are reluctant to speak Kazakh. While English has become more widespread and some of the Central Asian languages are mutually intelligible, Russian retains a status as a diplomatic, business, and civil society language for those working in multiple countries. Russia also remains a language of education. Over 200,000 Central Asians study in Russia, by far the largest destination in the world. Russian-language schools remain prominent at every level in Central Asia, from kindergarten to graduate schools. In short, while the usage of Russian is in slow decline, its position is relatively entrenched.” For cultural institutions, this reality means that distancing from Moscow politically does not automatically sever the linguistic infrastructure through which grants are written, exhibitions travel, and contracts are signed. Naima Morelli, an arts writer focused on contemporary art across Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, argues that the issue is less about elimination than coexistence. “For me, it makes sense that Russian continues to function as a practical operating language across Central Asia’s cultural infrastructure, as an inherited connective tissue of sorts. In the hypothesis of getting rid of it, the most obvious alternative for a shared language for exchanges across countries in Central Asia is English, which the global art world - in Central Asia as elsewhere - already widely employs and often considers more ‘neutral.’ But is any language truly neutral? As I see it, English carries its own hierarchies of power,” Morelli told TCA. “Of course, Russian does not bear the same perceived neutrality. The colonial legacy the Russian language carries is, in fact, addressed in the work of many Central Asian artists. Carrying something from the past, even something tied to a painful history, can still be productive and somewhat enriching, if we are able to repurpose it. We can see it clearly in Soviet architecture, so why not in the language? I think that instead of erasing Russian altogether, what would be ideal – albeit not so easy to achieve – is a polyphony: a cultural field where Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Russian, and English coexist, and are used depending on the context, reflecting what is the extremely layered identity of the region today.” Beyond institutional circles, however, the position of the Russian language has gradually weakened, particularly among younger generations educated primarily in national languages. In parts of the region, especially Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, its role in schooling and public life has narrowed, while English increasingly attracts urban youth seeking international opportunity. Yet for many artists, Russian is simply the most efficient way to be legible. National languages are emotionally central, but institutionally uneven. Terminology for contemporary art, critical theory, conservation, or curatorial practice is often underdeveloped, inconsistently translated, or unfamiliar to decision makers. Writing a proposal in Kazakh or Uzbek can feel like an act of cultural assertion, but also a risk. Russian offers precision, shared references, and the assurance that a jury will understand exactly what is being proposed. English occupies a different position. It is the primary language of global art markets, biennials, international foundations, and increasingly of youth. But the level of fluency required for contract negotiations, conceptual writing, and institutional correspondence remains limited to a relatively small cohort of artists and administrators. For those who possess it, English can function as a passport. This produces a quiet linguistic ladder that few institutions openly acknowledge. Local languages serve identity and symbolism. Russian underpins operation and legitimacy. English delivers visibility and international validation. The uncomfortable truth is that ascending this hierarchy often determines who is seen, funded, or invited abroad. The consequences of this system become clearest when language policies change. When institutions announce a switch away from Russian towards national languages, the move is usually framed as progressive and overdue. But access does not expand evenly. Older audiences educated in Soviet or early post-Soviet systems often lose their ability to engage with contemporary exhibitions. Independent artists from rural regions, who rely on Russian as a professional lingua franca, can find themselves cut off from institutional conversations that now presume fluency in a standardized national language they may not fully command. These tensions are not abstract. In Uzbekistan, Alisher Qodirov, a member of parliament, recently criticized the continued dominance of Russian in public services and education, arguing that reliance on Russian language schools and administration undermines the status of Uzbek as the state language and weakens cultural sovereignty. This reflects a broader regional discomfort: even where national languages are legally prioritized, Russian often remains embedded in institutional practice and professional life. The friction lies not between culture and politics, but between symbolism and administrative reality. Grant cycles and exhibition seasons, which often launch in February and March, are where these tensions surface most clearly. Calls for proposals quietly specify language requirements. In many cases, applications, correspondence, and legal contracts continue to default into Russian. Contracts are drafted in Russian legal language, even when public-facing mission statements emphasize linguistic revival and cultural sovereignty. The gap is rarely acknowledged publicly. The region operates in pragmatic multilingualism. Decolonization is the rhetoric; institutions remain bilingual or trilingual, and international correspondence often defaults to English. Language shapes authority. The language of funding and evaluation determines which narratives travel. National languages are visible in culture but are still consolidating their role in contracts, critiques, and institutional power. Russian is declining symbolically, but operationally persistent.

From Security Threat to Economic Partner: Central Asia’s New ‘View’ of Afghanistan

Afghanistan is quickly becoming more important to Central Asia, and the third week of February was filled with meetings that underscored the changing relationship. There was an “extraordinary” meeting of the Regional Contact Group of Special Representatives of Central Asian countries on Afghanistan in the Kazakh capital Astana. Also, a delegation from Uzbekistan’s Syrdarya Province visited Kabul, and separately, Uzbekistan’s Chamber of Commerce organized a business forum in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif. A Peaceful and Stable Future for Afghanistan The meeting in Astana brought together the special representatives of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for Afghanistan. The group was formed in August 2025. There was no explanation for why the fifth Central Asian country, Turkmenistan, chose not to participate. The purpose of the Astana meeting was to coordinate a regional approach to Afghanistan. Comments made by the representatives showed Central Asia’s changing assessment of its southern neighbor. Kazakhstan’s special representative, Yerkin Tokumov, said, “In the past [Kazakhstan] viewed Afghanistan solely through the lens of security threats… Today,” Tokumov added, “we also see economic opportunities.” Business is the basis of Central Asia’s relationship with the Taliban authorities. Representatives noted several times that none of the Central Asian states officially recognizes the Taliban government (only Russia officially recognizes that government). But that has not stopped Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, in particular, from finding a new market for their exports in Afghanistan. Uzbekistan’s special representative, Ismatulla Ergashev, pointed out that his country’s trade with Afghanistan in 2025 amounted to nearly $1.7 billion. Figures for Kazakh-Afghan trade for all of 2025 have not been released, but during the first eight months of that year, trade totaled some $335.9 million, and in 2024, amounted to $545.2 million. In 2022, Kazakh-Afghan trade reached nearly $1 billion ($987.9 million). About 90% of trade with Afghanistan is exports from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. For example, Kazakhstan is the major supplier of wheat and other grains to Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan is the biggest exporter of electricity to Afghanistan. Kyrgyzstan’s trade with Afghanistan is significantly less, but from March 2024 to March 2025, it came to some $66 million. To put that into perspective, as a bloc, the Central Asian states are now Afghanistan’s leading trade partner, with more volume than Pakistan, India, or China. Kazakhstan’s representative, Tokumov, highlighted Afghanistan’s strategic value as a transit corridor that could open trade routes between Central Asia and the Indian Ocean. Kyrgyzstan’s representative, Turdakun Sydykov, said the trade, economic, and transport projects the Central Asian countries are implementing or planning are a “key condition for a peaceful and stable future for Afghanistan and the region as a whole.” The group also discussed humanitarian aid for Afghanistan. All four of these Central Asian states have provided humanitarian aid to their neighbor since the Taliban returned to power in August 2021. Regional security was also included on the agenda in Astana, but reports offered little information about these discussions. A few days before the opening of the meeting in Astana, Russian Ambassador to Kyrgyzstan Sergei Vakunov spoke about the airbase in Kant, Kyrgyzstan, used by the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Vakunov said the base was capable of handling any “security threat to member states along the southern flank.” Vakunov was almost certainly referring to Tajikistan, which is the southern flank of the CSTO and shares a 1,350-kilometer border with Afghanistan. Since last summer, there have been several deadly clashes along a section of the Tajik-Afghan border, including two incidents that left at least five Chinese workers in the area dead. Tajikistan’s Counter-Narcotics Agency reported in early February that drug interdiction efforts along the border with Afghanistan in 2025 led to the seizure of 2.742 tons of narcotics, more than 50% higher than in 2024. The other Central Asian countries, including Turkmenistan, have engaged with the Taliban leadership since the first days after the group’s return to power. Tajikistan has taken a slower, cautious path in its relations and remains the only country in Central Asia where the ambassador from the Ashraf Ghani government that preceded the Taliban is still occupying the embassy. However, the Afghan consulate in the eastern Tajik border town of Khorog is staffed by Taliban representatives. Tajikistan’s embassy in Kabul remains open, and the Tajik ambassador met with Taliban Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi at the start of February to discuss border security. The presence of the Tajik representative at the Astana meeting is a further encouraging sign that Tajikistan is joining with its Central Asian neighbors to create a common policy toward Afghanistan. Business with Uzbekistan A delegation from Uzbekistan’s Syrdarya Province visited Kabul for a February 16-18 business forum. Syrdarya Governor Erkinjon Turdimov led the delegation. Deputy advisor to the Uzbek president, also director of the International Institute for Central Asia, Javlon Vahabov, was also there. The Uzbek delegation met with several top Taliban officials, including Foreign Minister Muttaqi and Minister of Industry and Trade Nuriddin Azizi. Governor Turdimov also met with the governor of Afghanistan’s northern Balkh Province, Muhammad Yusuf Wafa, to discuss trade. Balkh is the only Afghan province that directly borders Uzbekistan. Wafa is becoming a point man for the Taliban’s relations with Central Asia. The Balkh governor visited Tajikistan in October 2025 and met with Tajik security chief Saymumin Yatimov. The forum ended with Uzbek and Afghan representatives signing 25 deals worth some $300 million. The agreements covered “construction, food products, agriculture, furniture production, textiles, and pharmaceutical cooperation.” The provincial capital of Balkh is Mazar-i-Sharif. Uzbekistan’s Chamber of Commerce brought together more than 150 Afghan businessmen and representatives from more than 50 companies from Uzbekistan for a business forum in Mazar-i-Sharif, also conducted from February 16-18. Preliminary agreements worth potentially more than $200 million were signed. A Window of Opportunity The Central Asian states share the goals of increasing trade with Afghanistan and opening up routes through that country that connect them to Pakistani ports on the Arabian Sea. Afghanistan’s northern neighbors are also well aware that security and stability in Afghanistan are important in Central Asia. Since the five Central Asian countries became independent in late 1991, they have been contending with instability and uncertainty along the southern border. The situation in Afghanistan currently, while far from ideal, is nonetheless the most stable it has been in all the years of independence in Central Asia. Figures for Kazakh-Afghan and Uzbek-Afghan trade demonstrate for all of Central Asia the potential of engaging with Afghanistan.

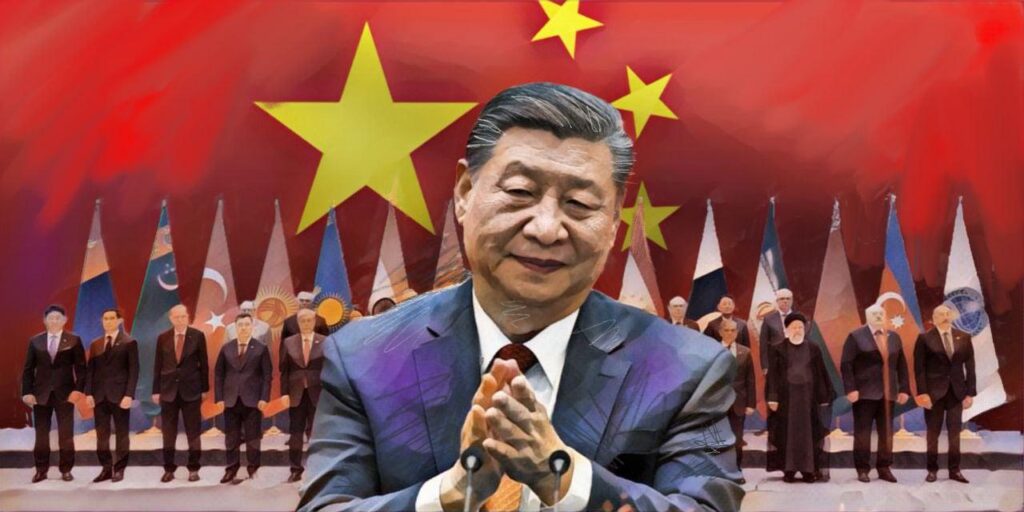

Kyrgyzstan Between the Russian World and Global Chaos: An Interview With Deputy Prime Minister Edil Baisalov

Edil Baisalov is a politician who began his career as a civil-rights activist, became a prominent member of Kyrgyzstan’s non-governmental organization (NGO) sector, and is now serving as the country’s Deputy Prime Minister. In an exclusive interview with The Times of Central Asia, he explained not only how his views have changed over the years, but also how Kyrgyzstan is seeking to find its place in what he described as a rapidly changing global landscape. In Baisalov’s assessment, the global system is facing a crisis of democracy. “The world order, as we know it, is collapsing – or at least is under attack from both within and without,” Baisalov told TCA. “The era of global hypocrisy is over, and the people of Kyrgyzstan have woken up. “What various international institutions have taught us over the years – their lectures on how to develop an economy, how to pursue nation-building, and so forth – has been proven wrong. Throughout the 1990s, Kyrgyzstan was one of the most diligent students of the liberal policies promoted by the “Chicago Boys.” We followed their instructions to the letter. Kyrgyzstan was the first post-Soviet country to join the World Trade Organization in 1998, and we were the first to receive normalized trade relations with the U.S. with the permanent repeal of the Jackson-Vanik amendment. All of our previous governments followed IMF conditionality dictates to the letter, especially in deregulation, mass privatization, and all the austerity programs and budget sequestrations. We were promised prosperity; that the free markets and the invisible hand would take care of everything. But it did not work. “I remember it well: at the time, U.S. President Bill Clinton laughed at China, saying that Beijing needed to adopt certain policies, to liberalize, or that science could not prosper in a closed society. He claimed the Chinese model was doomed to fail, arguing that scientific and technological breakthroughs could only occur in a Western-style society with minimal state intervention. Yet today, we witness the triumphant rise of the People’s Republic of China. This is not only an emergence but also a return to the rightful place of a great civilization that has, for millennia, contributed enormously to humankind.” TCA: Does this mean you now see China, rather than the West, as a model for Kyrgyzstan to follow? Baisalov: It’s not about the Chinese model or any particular foreign template. What we understood is that as a nation, we are in competition with other nations. Just like corporations compete with each other, nations must look out for themselves. If our state does not actively develop industries and sciences, there is no formula for success. All those ideologies promoting the “invisible hand” – the idea that everything will naturally flourish on its own – are simply false. TCA: When did Kyrgyzstan stop taking orders from outside forces and begin making independent national decisions? Baisalov: We used to be naive about wanting to be liked by others. But not anymore. In the last five years of our development, most of what we did went against the prescriptions of outside forces. We realized that it wasn’t just about following advice – it was about maturing as a nation and taking responsibility for ourselves. Now, we are pursuing a pragmatic course of development and making decisions based on our own best interests. TCA: It seems this change came about when you became Deputy Prime Minister. Baisalov: I didn’t want to join President Sadyr Japarov’s team initially. They tried to recruit me, but I resisted. However, I am proud that I eventually accepted his proposal. I’m very proud of our achievements. This country is three times richer than it was five years ago. I could leave tomorrow and spend the rest of my life proudly, knowing what I have significantly contributed to the development of Kyrgyzstan. But for the time being, I’m serving my nation. I believe there is no higher calling than that. TCA: How do you see President Japarov’s future in light of his recent decision to dismiss Kamchybek Tashiyev as head of the State Committee for National Security and Deputy Prime Minister? Baisalov: I strongly believe that President Sadyr Japarov will be reelected, and I’m looking forward to the presidential election next January. There may be some interesting developments and strong contention, but I don’t believe General Tashiyev will run for president, even though many people are urging him to do so. General Tashiyev is a great patriot, and he will not risk the stability of this country. I believe he will endorse President Japarov, as he has publicly pledged on numerous occasions. TCA: You argue for a stronger presidential system now, while in the past you supported a rather liberal model. How did your attitude change? Baisalov: I used to be a very individualistic libertarian, but I changed. The whole world has changed, not just me. TCA: Are you more conservative now? Baisalov: I’m probably more conservative than I used to be, but I’m still much more liberal than most people in my country. If I were from Moldova, Georgia, or Serbia, I wouldn’t be in politics. I would have gone into business or emigrated. Because sooner or later, all these countries will join the European Union. There’s no choice; it’s just a matter of time – of course, if the EU doesn’t collapse before then. But right now, the EU is like a huge magnet, a very attractive model that draws you in. Here in Kyrgyzstan, we don’t have a choice between the EU and the Eurasian Economic Union. We are here, and we are doing what we must do. That’s why I’m in this fight – because I want to steer this country toward the best possible outcome. TCA: Why did you recently say that Kyrgyzstan was forced into the Eurasian Union? Baisalov: I criticized the then national leadership for selling Kyrgyzstan’s accession to the Eurasian Economic Union as if we would automatically reap all the benefits. At the time, we really didn’t gain much. Other EAEU member states have significant exports, but for us, besides a few mineral resources, mainly gold, the main “export” is our labor to Russia and Kazakhstan. One supposed benefit is the free movement of labor. Theoretically, under Union law, Kyrgyz citizens have the fundamental right to work in Russia on equal terms with Russian citizens. But in reality, it’s not working. Most recent legislation in Russia actually places our labor migrants in the same category as migrants from neighboring Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, who are not even members of the EAEU. TCA: Does that mean you plan to leave the EAEU? Baisalov: We don’t have such plans. What we actually want is to attract foreign investors – for example, to build a manufacturing base here in Kyrgyzstan, as that would give them access to the Eurasian market. We want to take full advantage of our membership in the EAEU. TCA: While you aim to improve the status of Kyrgyzstan’s labor migrants in Russia, at the same time, you have a growing number of foreign workers in Kyrgyzstan. Baisalov: We had a big argument inside the Cabinet and the Presidential Administration. Of course, we want to provide jobs in our growing economy for our own people. In the social sector of the Cabinet, some of us, including myself, wanted to protect the market and put up barriers to foreign workers. But we were overruled by the pro-business part of the Cabinet. They argued that our construction boom needs foreign laborers, and our expanding manufacturing base – especially in the garment industries – faces challenges because the salary expectations of our own nationals are already too high, making us less competitive. So yes, we already have at least 25,000, if not more, foreign workers. This is a very unique experience for us. TCA: Your critics would say that if you cannot provide jobs to your own people, why bring in foreign workers? Baisalov: The world is not black and white. There are no easy solutions. My instinct was to protect our own labor market and only allow highly qualified foreign workers. But the pro-business part of the Cabinet won the argument. Even for the construction of the Presidential Administration, we initially relied on our own workforce, but in the end, we had to bring in foreign workers. We have moved from one way of thinking to another. That is why we now follow a very pragmatic path of development that prioritizes our national well-being and prosperity. In a way, this coincides with what has happened in the United States. TCA: In what way? Baisalov: I remember very well in the 1990s, NAFTA – the North American Free Trade Agreement – was presented as a globalist project that would improve the lives of every American family while helping develop Canada and Mexico. But the reality is different. I’ve seen small towns in America devastated, and I completely understand why the vast majority of American voters, who have been negatively affected by this globalist system, are choosing to vote for Trump and support the America First approach. TCA: Speaking of “America First” and protecting national interests, you recently said that Kyrgyzstan is part of the Russian world. How does that view fit into your vision of national priorities? Baisalov: My statement was misinterpreted, and some people, both in Kyrgyzstan and abroad, even accused me of being “sold out” to the Russians. There were many negative comments. But what I said is simply a fact. The average Kyrgyz villager, when using social media, watching Hollywood movies, or researching something online, overwhelmingly consumes this content in Russian. It’s a fact. I even consider it a failure of our national elites and cultural institutions that our children grew up watching Hollywood movies and cartoons in Russian. TCA: Do you plan to change that? Baisalov: There are countries that have built their national identity on not being Russia, or being “anti-Russia.” Former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma even wrote a book, Ukraine is not Russia. There are also quite a few activists in Kyrgyzstan who are promoting an anti-colonial narrative. I am not among them. I do believe that we need to build a strong Kyrgyz identity, but it should not be based on anti-Russian sentiment. I believe we must preserve the Russian language. We are bilingual, and we are proud of it. For example, our children, by default, are much smarter than many monolingual people. Studies even say it can give you around 20 extra IQ points. TCA: Do you personally feel yourself as part of the Russian world? Baisalov: I don't live in the Russian world. I read The New York Times, Svenska Dagbladet, The Economist, or Hürriyet. I’m glad that I can also watch Hollywood movies in English. I’m cosmopolitan, and I strongly believe that our people should also learn to speak English – but not at the cost of abandoning the Russian language.

Japarov Breaks the Kyrgyz Tandem

When Kamchybek Tashiyev returned to Bishkek from medical travel abroad after losing his post as Chairman of the State Committee for National Security (GKNB), as well as the deputy chairmanship of the Cabinet of Ministers, he returned to a system already being disassembled. Kyrgyzstan’s President Sadyr Japarov dismissed him on February 10, ending a five-year arrangement in which the presidency and the security apparatus were closely fused. The decision deliberately dismantled the governing tandem that had defined Kyrgyzstan’s power structure since 2020. The immediate question was whether this was a closing of an episode or the opening of a new one. The first wave of moves suggests the latter: a transition toward a more personalized presidency, with the internal-security bloc fractured and its succession logic unsettled. Japarov publicly framed the decision as preempting an institutional split. He explicitly pointed to parliamentary groupings that began sorting deputies into “pro-president” versus “pro-general” camps. Russian-language coverage has tended to present the episode as an effort to end a dual-power configuration, not merely to remove one official. This narrative implies that the state’s operative center of gravity had already begun drifting away from predictable office-holding and toward informal allegiance tests. Once such a dynamic becomes evident, according to such a telling, the preservation of regime coherence often requires rapid, coercive re-centering. Domestic Political Configurations The first domestic signal was indeed speed. Along with Tashiyev, senior security officials were removed, and an acting head was installed pending parliamentary procedures. The point here was not just about personnel but about the timing: the presidency moved first, then moved again, so that no alternative pole could consolidate inside the security institutions. If the system had been built around a Japarov–Tashiyev tandem, then the immediate dismantling of Tashiyev’s proximate layers was also a message to the broader stakeholder society that the presidency would decide who inherits the southern security networks and clan linkages. Japarov was clearly conveying a signal of dominance that ruled out negotiation. A second signal came through parliament. Speaker Nurlanbek Turgunbek uulu resigned shortly after the dismissal, amid reporting that he was politically close to Tashiyev and vulnerable once the security bloc shifted. Russian reporting treated the speaker’s resignation as part of the same chain reaction set off by the February 10 decree. This was part of a pattern whereby institutional actors in Kyrgyzstan’s domestic politics reorient quickly toward whoever appears to be winning in the short term. Loyalty is anticipatory because the penalty for backing the wrong camp can arrive through law enforcement, prosecutorial pressure, or reputational destruction. A third signal emerged through the revived early-election debate. The open-letter campaign and talk about a “snap election” did not arise in a vacuum; it built on a preexisting argument about constitutional timing and mandate renewal. That development provided a political vocabulary for testing whether the tandem’s first stage had ended. The credible possibility of early elections has destabilized patronage, compelling every member of the political class at every level to recalculate expectations. Every political actor has been forced to reassess political loyalty, mobilization capacity, and regional leverage. The fourth domestic signal was the continuity of coercive habit. Under Tashiyev, the GKNB repeatedly treated even low-grade political discussion as a potential precursor to “mass unrest,” including high-profile cases against opposition figures before elections. That background makes the present moment awkward: if the letter campaign and associated machinations were undertaken without Tashiyev’s knowledge, then it exposes a severe lapse of control inside the system he claimed to run; however, if he encouraged these maneuvers as a pressure mechanism, then the rift with Japarov is no longer an internal reshuffle but a failed attempt to accelerate succession politics. Both possible interpretations point toward structural fragility rather than orderly transition. International Implications These domestic dynamics spill outward because Kyrgyzstan is a regional bellwether precisely when it is least predictable. The country has a history of rapid political reversals, recurrent elite fragmentation, and street-linked legitimacy crises. These have repeatedly forced external powers to reassess how they manage influence and risk. For Russia and China, the problem is not ideological but operational. Both countries have treated Kyrgyzstan as a core territory for security management and regional connectivity. Both prefer dealing with stable domestic hierarchies, but the political risk produced by uncertainty increases transaction costs. A personalized presidency paired with a fractured security bloc degrades their ability to rely on any single channel. Sanctions politics sharpen the external stakes. Kyrgyzstan has been under sustained Western scrutiny over re-export and sanctions-evasion pathways connected to Russia’s war against Ukraine. The timing of Tashiyev’s dismissal and the accompanying elite uncertainty raise the likelihood that sanctions compliance becomes inconsistent across agencies, private intermediaries, and political patrons, even if the presidency attempts to impose discipline. In other words, institutional fragility in Kyrgyzstan is not just a domestic governance problem but a transactional risk for foreign economic partners. Russia’s immediate concern is whether the dismissal represents consolidation or instability. As noted above, Russian commentary has presented the move as ending a dual-power arrangement and reasserting presidential primacy, but it has also pointed to the uncertainty of the transition and the possibility that the “system” built under the security chief could unravel. Moscow has seen Bishkek swing rapidly between political centers in the past, and it has seen how intra-elite conflict can spill into broader mobilization. A more personalized presidency can look like consolidation; however, the increased centralization can also become a single point of failure if elite sabotage rises. Authoritarian centralization in Kyrgyzstan is not inherently destabilizing from Moscow’s or Beijing’s perspective. Both powers are accustomed to dealing with dominant executives, but they prefer regimes in which coercive capacity is distributed across multiple loyal structures rather than concentrated in a single personalized node. Such a “pluralism” of security structures, even if they compete with one another, facilitates succession management, internal monitoring, and resilience during a crisis. A “unipolar” consolidated regime, by contrast, carries the risk of hardening into brittleness. China’s calculus differs in form but not in substance. Beijing is less exposed to Kyrgyzstan’s domestic legitimacy narratives, but it is deeply exposed to the risk of administrative incoherence in the state structure. That is especially the case where Chinese firms, lenders, and contractors rely on predictable enforcement and protection. Tashiyev’s dismissal destabilizes the informal patron-client equilibrium upon which many large projects depend for perimeter control, problem-solving capacity, and administrative continuity. If regional networks begin testing the new boundaries or if political replacements are contested, then not even a strong presidency relying on authoritative rhetoric can substitute for a coherent security bloc. Succession Without a Second Pole Whether this episode settles or metastasizes will depend in part upon Tashiyev’s own posture. Reporting based on Kyrgyz media has described his dismissal as unexpected and emphasized his public acceptance of the presidential decision. If Japarov has offered a graceful exit, that offer holds only if Tashiyev’s networks do not interpret such restraint as weakness and begin freelancing to preserve their own positions. The succession question inside the system of security institutions remains the central domestic variable. The entire architecture of recent years was built on the tandem of Japarov as the institutional face and Tashiyev as the coercive hardball player who was also influential across multiple policy domains. Removing the second pole leaves the presidency with a choice. Either it recreates a comparable enforcer, or it distributes security power across multiple actors, but the latter strategy increases coordination costs and the risk of intra-elite sabotage. The pressure on the sub-elites is heightened by changes already underway in electoral rules that are reshaping how regional patrons imagine their future bargaining power. For external observers, events underscore Kyrgyzstan’s established significance as a bellwether for how Russia and China manage volatility at the core of their shared neighborhood. If Japarov succeeds in recentralizing coercive capacity without provoking regional backlash, then Moscow and Beijing can treat the episode as consolidation and resume routine transactional politics. But if the unraveling continues, both will adjust by hedging across domestic factions and by demanding tighter guarantees for any security-sensitive or capital-intensive engagement. Either way, Tashiyev’s dismissal marks the start of a new chapter in the Japarov era, not the resolution of the last one.

Coordination Instead of Declarations: Astana Hosts Meeting of Regional Contact Group on Afghanistan

On Monday, Astana hosted an extraordinary meeting of the Regional Contact Group of Special Representatives of Central Asian Countries on Afghanistan, with delegations from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan in attendance. The agenda focused on trade and economic cooperation with Afghanistan, including joint projects, investment protection, transit tariff policy, and the development of transport corridors through Afghan territory. The establishment of the group represents the practical implementation of agreements reached at the Sixth Consultative Meeting of the Heads of State of Central Asia, held in Astana in August 2024, and reflected in the Roadmap for Regional Cooperation for 2025-2027. The first meeting of the Contact Group took place on August 26 last year in Tashkent. As noted by Erkin Tukumov, Special Representative of the President of Kazakhstan for Afghanistan, Astana is interested in a constructive exchange of views and in identifying practical solutions to pressing issues of cooperation with Afghanistan. In recent years, Kazakhstan has consistently kept Afghanistan among its foreign policy priorities, avoiding rhetorical declarations in favor of a measured and systematic approach. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev has paid particular attention to Afghanistan since the change of power in Kabul in 2021. In the first weeks after the Taliban assumed control, Astana began articulating its position on international platforms. One of the key statements was Tokayev’s address at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit in Dushanbe on September 17, 2021. He advanced a thesis that has since been reiterated in various formats: Afghanistan should be viewed not only as a source of risk but also as a potential driver of regional development, provided that stability and economic recovery are achieved. This position was further elaborated days later at the United Nations General Assembly. At that time, Kazakhstan was among the first to emphasize the need for inclusiveness in Afghanistan’s future political system, not as an abstract requirement, but as a practical condition for stability. Another significant step was the creation last year of the post of Special Representative of the President for Afghanistan, to which Tukumov was appointed. This role goes beyond that of an interdepartmental coordinator: as a direct representative of the head of state, it elevates the Afghan portfolio to the level of strategic priority. The establishment of such a position signals a transition from a situational response to a more systematic policy. The Astana meeting confirmed the intention of regional countries to deepen cooperation through a regular platform capable of coordinating actions and presenting them externally in a consolidated manner. Some external observers suggest that Central Asian countries are only now beginning to develop a common position on Afghanistan. However, that position has largely taken shape in recent years. The current task is not to formulate it, but to coordinate it more precisely. The meeting in Astana demonstrated that, for Central Asian countries, the primary concern is not the nature of the regime in Kabul, but Afghanistan’s capacity to function as a predictable economic partner and responsible participant in international relations. For the region, it is essential that its southern neighbor operate in accordance with generally accepted economic standards, ensure reliable transit management, and integrate into regional cooperation frameworks. The objective is to anchor Afghanistan within the regional context, not as an object of concern or threat, but as a full-fledged participant in discussions on water resources, security, logistics, and environmental issues. Efforts in recent years to establish broader international formats on Afghanistan have repeatedly encountered contradictions, given the diversity of external interests and the heavy political burden involved. The Central Asian format differs fundamentally: it is an intra-regional dialogue. There is no external arbitration, no competing geopolitical agendas, and the focus remains on practical matters. For Central Asia, Afghanistan is not an abstract issue of global politics, but a direct neighbor. This pragmatism is gradually assuming an institutional form, effectively shaping a regional Afghanistan track initiated and coordinated by the countries of Central Asia themselves.

Afghanistan has not yet responded to the Contact Group meeting. However, the event has attracted attention in the Afghan media. Some media outlets note that the country's inclusion in regional processes is in the interests of not only Afghanistan itself, but also its neighbors. In particular, the idea was raised that the countries of Central Asia are capable of playing the role of “positive mediators” in building a pragmatic line of interaction with Kabul.

Germany Builds a Z5+1 in Central Asia

Germany’s meeting on February 11 with the five Central Asian foreign ministers in Berlin formalized the Z5+1 (“Z” for “Zentralasien”) format as a standing work channel. It joins other “plus-one” formats now crowding Central Asia that function as instruments of influence. The United States is using C5+1 to push a more deliverables-oriented agenda, including critical raw materials, and China has institutionalized leader-level summitry with accompanying treaties, grants, and transport-centered integration. The EU has elevated its relationship to a strategic partnership and is putting Global Gateway branding behind connectivity and investment. Germany’s Z5+1 is best understood as Europe’s effort to add a practical, tool-driven channel that can move faster than EU consensus in some domains while still feeding EU programming rather than competing with it. The concluding Berlin Declaration reads like a program sheet with named instruments, sector priorities, and established a direct link to the EU’s broader “Team Europe” posture through the participation of EU Special Representative Eduards Stiprais. Germany’s Z5+1 fits this competitive field as a European execution lane that can move projects forward with German instruments while staying aligned with EU programs. Berlin Defines the Tools The Z5+1 meeting in Berlin drew on a sequence that Germany has been building since its 2023 “Strategic Regional Partnership” and subsequent summits in Berlin (2023) and Astana (2024), with an explicit emphasis on Central Asian regional cooperation as a counterpart to bilateral ties. The Berlin meeting, therefore, did not attempt to invent a new regional architecture but rather added a stable ministerial format for pushing forward project lists, regulatory expectations, and finance conditions between higher-level meetings. In Berlin, Germany committed €2.7 million to a cooperation platform for the Trans-Caspian Transport Corridor: a small sum by infrastructure standards, but targeted at unglamorous coordination like data-sharing, planning discipline, and institutional continuity, i.e., standards and transborder management regimes where corridor initiatives often stall. This profile complements the EU-backed Trans-Caspian Coordination Platform track, which is explicitly tied to a wider €10 billion commitment announced at the January 2024 Global Gateway investors forum for EU–Central Asia transport connectivity. and which has addressed the corridor less as a construction problem than as a finance-and-sequencing problem. Berlin also explicitly supported the commercial participation of German rail and logistics firms in transport and consulting projects, aligning with the intent to keep firm-level engagement attached to ministerial diplomacy. The declaration references export credits and investment guarantees, and links them to business-environment expectations. On the same day, the German Eastern Business Association convened a “Wirtschaftsgespräch” (economics talk) in the Foreign Office with the Central Asian delegations. There, the region was framed as strategically significant for Germany’s diversification agenda, and it was signaled that an autumn leaders’ summit is already in view. Germany’s public accounting of its regional engagement in Central Asia stresses its already-deep base of activity in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in particular, including dozens of projects and multi-billion-euro volumes. The energy transition was mentioned, as the Berlin Declaration points to renewables, hydrogen, and climate programming that Germany is already funding and can expand through existing channels. These include the “Green Central Asia” initiative backed by a €250 million commitment and additional regional development cooperation portfolios. Reporting by The Times of Central Asia on green-energy export ideas from Kazakhstan, and on the domestic controversy around the Hyrasia One hydrogen project, illustrates why Berlin’s approach is structured as a portfolio of smaller pilots, grid work, and efficiency projects, rather than as one mega-plan that can fail on permitting, water stress, or local opposition. Z5+1 in the Competitive “Plus-One” Ecosystem Berlin also treated sanctions compliance as a practical agenda item by including language on the prevention of circumvention and on coordination on sanctions-related risks. EU deliberations and reporting on possible anti-circumvention measures already include scrutiny of re-export channels. This creates direct exposure for Central Asian economies that have benefited from gray-zone trade since 2022. As a gatekeeper for specific industrial goods and finance tools, Germany is positioned to translate this into concrete expectations of sanctions compliance. One lever is programming under the "security" rubric that often functions as infrastructure and services in border regions. Berlin has dedicated more than €13 million in financial support for OSCE regional projects since 2022, with a €3 million contribution in 2025 to the OSCE fund responding to Afghanistan-related issues, including water and conflict management. It also reiterates cross-border stabilization programming that has direct local effects in border regions, where hard infrastructure, services, and administrative capacity are often inseparable from “security” labels. The U.S. channel provides a useful comparison. A more deliverables-oriented U.S. C5+1 track has elevated critical raw materials, and the associated dialogue mechanisms have been presented as a concrete area for practical cooperation, including the launch of the C5+1 Critical Minerals Dialogue. Germany’s Z5+1 is not seeking to replicate the U.S. working-group architecture. Likewise, Germany will not outspend China, which has used leader-level summitry to consolidate a long-horizon political umbrella for infrastructure and trade integration, including treaty-level upgrading of ties and grant commitments alongside transport projects. China used its first China–Central Asia summit in 2023 to define a new platform and embed security and capacity-building language alongside economics. Operational Implications Germany’s Z5+1 is a standing work channel that links German export credits and investment guarantees to corridor governance, critical minerals, and energy-transition project pipelines. It treats sanctions-circumvention risk as a structuring constraint, bringing compliance management into project selection, financing terms, and due diligence rather than leaving it as ambient exposure. For the Central Asian five, this creates an additional diversification venue with more explicit discipline costs than many other “plus-one” tracks. As “C5+1” formats proliferate, Central Asian bargaining leverage increases, and demands on regional coordination and sanctions-risk management increase as well. Germany competes in that environment without creating a separate EU track, signaling Team Europe alignment through the EU Special Representative’s participation and by linking the channel to EU program pipelines shaped by Global Gateway financing and regulatory expectations. By design, Z5+1 makes corridor sequencing, financing terms, and sanctions-risk practices the locus of operational negotiation. Its practical effects will accumulate in corridor governance capacity, project bankability, and partner diversification under pressure from larger neighbors.

Sunkar Podcast

Central Asia and the Troubled Southern Route