Modernization Without Dependence: Why Uzbekistan Is Deepening Ties with Washington

The recent rise in Uzbekistan-U.S. engagement is often framed as a sudden diplomatic turn, and much of the commentary has focused on what Washington hopes to gain from deeper involvement in Central Asia. Far less attention, however, has been given to what Tashkent is seeking from this relationship. From Uzbekistan’s perspective, this engagement is part of a broader national strategy to expand the country’s foreign policy options at a time when all of the major powers are competing for influence in Central Asia. In November 2025, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev joined the other C5 leaders in Washington for a White House summit focused on economic cooperation, critical minerals, energy, and trade. By February 2026, the relationship had moved beyond talks and into financing and project design, with new agreements involving the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and EXIM, alongside a new critical minerals framework. From Uzbekistan’s side, the core objective is straightforward. Tashkent wants to modernize rapidly without risking becoming overdependent on any single external investor. That means using U.S. interest as leverage and in tandem with, not as a replacement for ties with Russia or China. Washington is courting the region because it wants access to minerals and supply chains that reduce reliance on China and limit exposure to sanctioned or geopolitically sensitive suppliers. Uzbekistan is well aware of this and is using that demand to strengthen its bargaining position for financing, technology, and industrial upgrading. In other words, Uzbekistan is positioning itself as a strategic production and transit partner. The direction of cooperation is revealing. The February 2026 U.S.-Uzbekistan critical minerals pact prioritizes the full-value chain from exploration and extraction to processing, and even proposes a joint investment holding company. This signals that Tashkent is aiming beyond raw-material exports. It wants to break from the post-Soviet pattern of shipping resources while others capture refining, technology, and margins. If it can secure processing capacity, infrastructure, and long-term financing, the deal becomes an instrument of industrial policy. The second objective is finance and implementation capacity. President Mirziyoyev also held separate bilateral meetings with the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, Howard Lutnick, and other senior U.S. trade officials. The meetings focused on an investment platform, business council coordination, and support for large industrial and infrastructure projects. EXIM also publicly described the new framework as a way to convert earlier commitments into financing solutions for energy, aviation, critical minerals, and advanced technologies. The third objective is trade normalization and market access. A bipartisan Senate effort has introduced legislation to repeal Jackson-Vanik restrictions for Central Asian states, and President Mirziyoyev raised U.S. support for Uzbekistan’s WTO accession and stronger cooperation under the U.S.–Central Asia Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA). These measures shape the legal and trade environment that ultimately determines investor confidence. Uzbekistan is trying to make the relationship durable by embedding it in institutions. The move also serves a domestic political economy logic. President Mirziyoyev’s government has spent years presenting itself as reformist, investment-friendly, and open for business. Deeper engagement with the United States strengthens that narrative both at home and abroad. The Uzbek presidency has highlighted that bilateral trade has passed $1 billion and that around 340 U.S. companies operate in the country, while also pointing to a three-year economic cooperation program and sectoral projects in energy, transport, agriculture, and IT. The leadership wants to show that reforms are producing major partnerships and that Uzbekistan is becoming a serious player in global supply chains. At the regional level, Tashkent is also using U.S. engagement to advance its leadership ambitions in Central Asia. Uzbekistan is seeking not only bilateral gains from Washington but a stronger role as a regional agenda-setter. President Mirziyoyev’s push for deeper regional institutionalization, including proposals for a “Community of Central Asia,” serves the same goal. U.S. interest in the C5 format gives Tashkent more room to maneuver on regional integration, supply chain coordination, and diplomatic coordination without appearing to tilt decisively away from Moscow or Beijing. Engagement with Washington, therefore, serves a regional strategy for Uzbekistan, not just a bilateral one. There are limits and risks. U.S. policy can be highly transactional, and Tashkent has seen this before; it will not assume Washington’s attention is permanent. Implementation gaps are also common in large cross-border infrastructure and industrial deals. Many of the agreements signed so far establish frameworks, heads of terms, and financing pathways, but execution will determine their impact. Meanwhile, Central Asian states remain closely tied to Russia, while China retains strong commercial influence. Tashkent’s challenge is to deepen ties with the United States without forcing a binary choice.

Pannier and Hillard’s Spotlight on Central Asia: New Episode Out Now

As Managing Editor of The Times of Central Asia, I’m delighted that, in partnership with the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, from October 19, we are the home of the Spotlight on Central Asia podcast. Chaired by seasoned broadcasters Bruce Pannier of RFE/RL’s long-running Majlis podcast and Michael Hillard of The Red Line, each fortnightly instalment will take you on a deep dive into the latest news, developments, security issues, and social trends across an increasingly pivotal region. This week, the team will be covering Kazakhstan announcing the date for its upcoming constitutional referendum, controversial polling decisions in Kazakhstan, a new fighting force forming that could make the Tajikistan–Afghanistan border even more volatile, one leader returning from an unexplained absence, and several others travelling to the United States for talks that are raising eyebrows. We'll also cover a major government reshuffle in Turkmenistan, before turning to our main story: the removal of one of Kyrgyzstan's most powerful figures, and the political and geopolitical aftershocks likely to follow. On the show this week: - Emil Dzhuraev (Political Expert)

Central Asia and the Global Water Crisis: A Test of Governance and Cooperation

Water scarcity is rapidly transforming from a regional environmental concern into one of the defining global security challenges of the 21st century. UN-linked assessments estimate that around four billion people experience severe water scarcity for at least one month each year, and nearly three-quarters of the global population lives in countries facing water insecurity.

Against this backdrop, Central Asia is not an exception but rather a concentrated example of global dynamics: climate pressure, population growth, and inefficient resource management. Regional initiatives, including proposals put forward by Kazakhstan, therefore have the potential to contribute not only to stability in Central Asia but to the development of a more coherent global water governance architecture.

The Water Crisis as a Global Reality

Water is increasingly regarded as a strategic resource on par with energy and food. Climate change is intensifying droughts, floods, and the degradation of aquatic ecosystems across all regions, from Africa and the Middle East to South Asia, Europe, and North America.

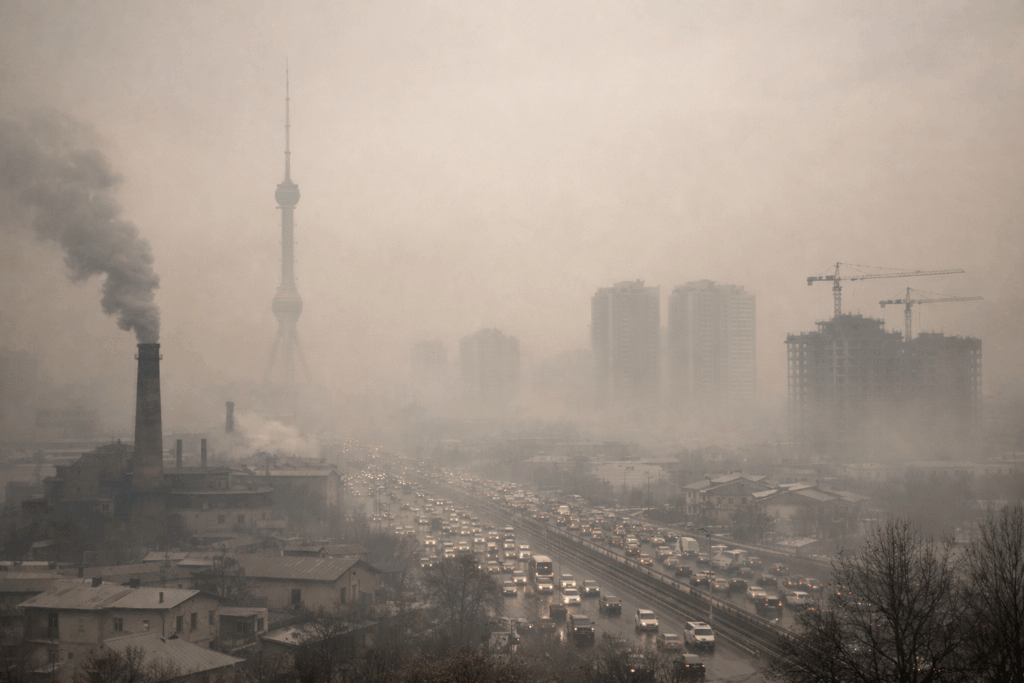

Recent mapping and analysis by investigative groups and international media indicate that half of the world’s 100 largest cities experience high levels of water stress, with dozens classified as facing extremely high levels. Major urban centers, including Beijing, New York, Los Angeles, Rio de Janeiro, and Delhi, are among those under acute pressure, while cities such as London, Bangkok, and Jakarta are also categorized as highly stressed.

In this context, Central Asia is not an outlier. It is confronting today what may soon become the global norm.

Central Asia: Where Global Trends Converge

A defining feature of the current environmental situation is that factors beyond natural ones drive the water crisis. Experts increasingly stress that shortages are often less about absolute physical scarcity and more about outdated management systems, infrastructure losses, and inefficient consumption patterns. In this respect, Central Asia can be seen as a testing ground for global water challenges, where multiple stress factors converge.

The region, with mountain peaks exceeding 7,000 meters, contains some of the largest ice reserves outside the polar regions. The Pamir and Hindu Kush ranges, together with the Tibetan Plateau, the Himalayas, and the Tien Shan, form part of what is sometimes referred to as the “Third Pole,” the largest concentration of ice after the Arctic and Antarctic.

[caption id="attachment_13410" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] The White Horse Pass, Tajikistan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

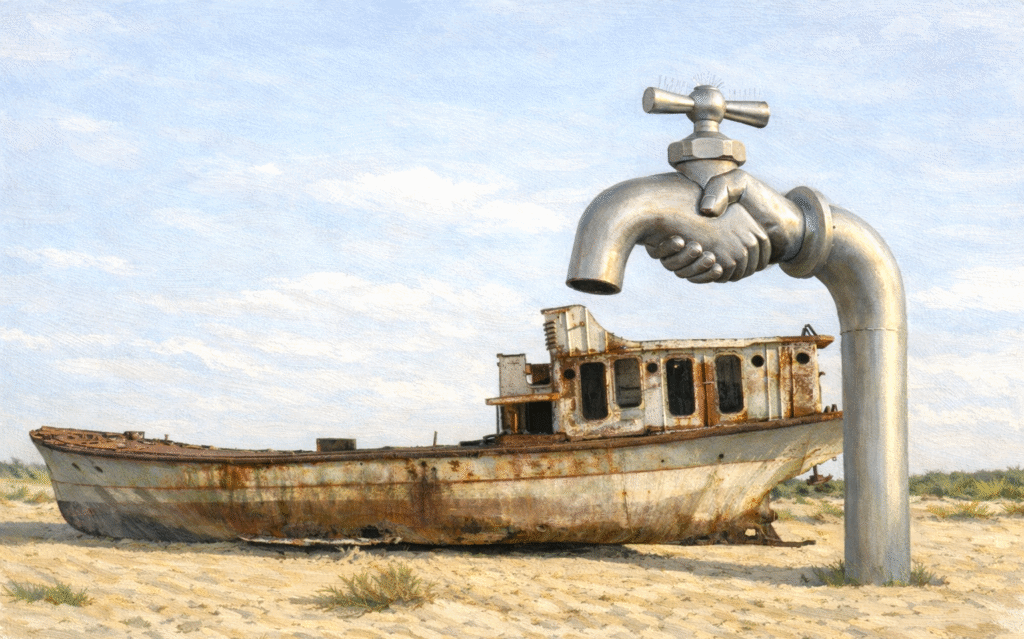

However, the pace of change is alarming. By 2030-2040, water scarcity in Central Asia risks becoming chronic. Glaciers in the Western Tien Shan, for example, have reportedly shrunk by roughly 27% over the past two decades and continue to retreat, posing a direct threat to the flow of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. These rivers increasingly fail to reach the Aral Sea in sufficient volume, while the exposed seabed has become a major source of salt and dust storms.

[caption id="attachment_21928" align="aligncenter" width="2560"]

The White Horse Pass, Tajikistan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

However, the pace of change is alarming. By 2030-2040, water scarcity in Central Asia risks becoming chronic. Glaciers in the Western Tien Shan, for example, have reportedly shrunk by roughly 27% over the past two decades and continue to retreat, posing a direct threat to the flow of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. These rivers increasingly fail to reach the Aral Sea in sufficient volume, while the exposed seabed has become a major source of salt and dust storms.

[caption id="attachment_21928" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Moynaq, Karakalpakstan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

Infrastructure inefficiencies compound the problem. Estimates suggest that in some systems, 40-50% of water can be lost in deteriorating canals and distribution networks before reaching end users. Agriculture accounts for approximately 80-90% of total water withdrawals, much of it directed toward water-intensive crops cultivated using outdated irrigation techniques. Meanwhile, the region’s population could grow by almost 25% by 2040 compared with current levels, placing additional pressure on drinking water supplies and public utilities.

Taken together, these factors make water scarcity not only an environmental and economic issue but also a potential source of social instability. In this context, water is gradually becoming a matter of domestic and regional security rather than solely a question of resource management.

The challenge of water security, particularly the use of transboundary rivers, lakes, and seas, as well as climate-related impacts on aquatic systems, has long transcended national borders. In Central Asia, this is reflected in asymmetries between upstream and downstream states. Globally, it manifests in growing tensions between regions with relative water abundance and those facing chronic deficits.

The United Nations has repeatedly warned that, under conditions of accelerating climate change, water could become a significant trigger of conflict in the 21st century. Developing global rules, monitoring systems, and early-warning mechanisms is therefore becoming as important as implementing national conservation programs.

Technology and Management: Unlocking Hidden Reserves

International experience demonstrates that a substantial share of water deficits can be mitigated through improved governance and technology. Properly designed and maintained drip irrigation systems can reduce water use by 30-50% compared with traditional surface irrigation while supporting higher yields and improved crop quality.

Laser land leveling can cut irrigation water use by 25-30% without reducing yields. It enhances water efficiency, reduces weed growth, and promotes more uniform crop maturation, while also lowering the volume of water required for field preparation.

Replacing open earthen canals with pipeline systems can significantly reduce conveyance losses. Digital water metering, sensors, satellite monitoring, and information technologies help transform water from an “invisible” input into a measurable and manageable asset. In urban settings, water meters, efficient plumbing fixtures, and the reuse of treated wastewater provide additional savings.

Across regions, experts reach a similar conclusion: the crisis stems less from climate conditions alone and more from outdated management models. Modernizing governance and infrastructure often delivers the most immediate and substantial gains.

Regional Cooperation as Part of the Global Response

For Central Asia, a central priority is shifting from competition to cooperation. Proposals such as the creation of an International Water and Energy Consortium for the region reflect efforts to reconcile upstream and downstream interests, integrate water and energy considerations, and reduce the risk of conflict.

In late 2025, the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia reached agreement on water allocations from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers for the 2025–26 non-growing season — setting specific quotas for each state and ensuring a minimum flow through key hydrological points and the Aral Sea delta — underscoring that shared management is an operational reality as well as a strategic imperative

The importance of such mechanisms extends beyond the region. They illustrate how transboundary resources can be governed through shared rules, transparent data, and mutual benefit, elements that remain underdeveloped in the global water management system.

In this context, the initiative proposed by Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to establish an International Water Organization within the United Nations framework carries broader significance. It represents not merely a regional proposal but an attempt to strengthen institutional foundations for global water governance.

Over the long term, such an organization could serve as a platform for developing universal principles of water management, facilitating data exchange and scientific cooperation, providing early warnings of emerging crises, and preventing transboundary disputes over allocation.

As water-related risks increasingly affect countries across continents, initiatives of this kind align with wider efforts to adapt to climate change and enhance resilience.

Central Asia as an Early Indicator of a Global Shift

Central Asia is not on the periphery of the global water crisis; it is an early indicator of broader trends. Developments in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya basins may foreshadow similar challenges elsewhere.

Water scarcity represents a global governance challenge affecting Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and advanced economies alike. The region, therefore, has the potential to act not only as a zone of risk but also as a source of practical solutions. If water diplomacy, technological innovation, and institutional reform can succeed here, their lessons may prove applicable worldwide.

Water has become a test of the capacity of states and international institutions to act strategically. The sustainability of global development in the 21st century will depend in part on how that test is met.

Moynaq, Karakalpakstan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

Infrastructure inefficiencies compound the problem. Estimates suggest that in some systems, 40-50% of water can be lost in deteriorating canals and distribution networks before reaching end users. Agriculture accounts for approximately 80-90% of total water withdrawals, much of it directed toward water-intensive crops cultivated using outdated irrigation techniques. Meanwhile, the region’s population could grow by almost 25% by 2040 compared with current levels, placing additional pressure on drinking water supplies and public utilities.

Taken together, these factors make water scarcity not only an environmental and economic issue but also a potential source of social instability. In this context, water is gradually becoming a matter of domestic and regional security rather than solely a question of resource management.

The challenge of water security, particularly the use of transboundary rivers, lakes, and seas, as well as climate-related impacts on aquatic systems, has long transcended national borders. In Central Asia, this is reflected in asymmetries between upstream and downstream states. Globally, it manifests in growing tensions between regions with relative water abundance and those facing chronic deficits.

The United Nations has repeatedly warned that, under conditions of accelerating climate change, water could become a significant trigger of conflict in the 21st century. Developing global rules, monitoring systems, and early-warning mechanisms is therefore becoming as important as implementing national conservation programs.

Technology and Management: Unlocking Hidden Reserves

International experience demonstrates that a substantial share of water deficits can be mitigated through improved governance and technology. Properly designed and maintained drip irrigation systems can reduce water use by 30-50% compared with traditional surface irrigation while supporting higher yields and improved crop quality.

Laser land leveling can cut irrigation water use by 25-30% without reducing yields. It enhances water efficiency, reduces weed growth, and promotes more uniform crop maturation, while also lowering the volume of water required for field preparation.

Replacing open earthen canals with pipeline systems can significantly reduce conveyance losses. Digital water metering, sensors, satellite monitoring, and information technologies help transform water from an “invisible” input into a measurable and manageable asset. In urban settings, water meters, efficient plumbing fixtures, and the reuse of treated wastewater provide additional savings.

Across regions, experts reach a similar conclusion: the crisis stems less from climate conditions alone and more from outdated management models. Modernizing governance and infrastructure often delivers the most immediate and substantial gains.

Regional Cooperation as Part of the Global Response

For Central Asia, a central priority is shifting from competition to cooperation. Proposals such as the creation of an International Water and Energy Consortium for the region reflect efforts to reconcile upstream and downstream interests, integrate water and energy considerations, and reduce the risk of conflict.

In late 2025, the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination of Central Asia reached agreement on water allocations from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers for the 2025–26 non-growing season — setting specific quotas for each state and ensuring a minimum flow through key hydrological points and the Aral Sea delta — underscoring that shared management is an operational reality as well as a strategic imperative

The importance of such mechanisms extends beyond the region. They illustrate how transboundary resources can be governed through shared rules, transparent data, and mutual benefit, elements that remain underdeveloped in the global water management system.

In this context, the initiative proposed by Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to establish an International Water Organization within the United Nations framework carries broader significance. It represents not merely a regional proposal but an attempt to strengthen institutional foundations for global water governance.

Over the long term, such an organization could serve as a platform for developing universal principles of water management, facilitating data exchange and scientific cooperation, providing early warnings of emerging crises, and preventing transboundary disputes over allocation.

As water-related risks increasingly affect countries across continents, initiatives of this kind align with wider efforts to adapt to climate change and enhance resilience.

Central Asia as an Early Indicator of a Global Shift

Central Asia is not on the periphery of the global water crisis; it is an early indicator of broader trends. Developments in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya basins may foreshadow similar challenges elsewhere.

Water scarcity represents a global governance challenge affecting Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and advanced economies alike. The region, therefore, has the potential to act not only as a zone of risk but also as a source of practical solutions. If water diplomacy, technological innovation, and institutional reform can succeed here, their lessons may prove applicable worldwide.

Water has become a test of the capacity of states and international institutions to act strategically. The sustainability of global development in the 21st century will depend in part on how that test is met.

Uzbekistan Joins a U.S. Critical Minerals Implementation Track

On February 4, 2026, in Washington, D.C., Uzbekistan’s Foreign Minister Bakhtiyor Saidov and U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau signed an intergovernmental Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on securing supply chains for critical minerals and rare earth elements, spanning both mining and processing. A further agreement signed on February 19 brought implementation and financing to the foreground. The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) signed “heads of terms” (i.e., commercial principles and essential terms of a proposed future agreement) for a Joint Investment Framework and outlined a proposed joint holding company. An agreement to establish an “investment platform” was exchanged in the presence of Uzbekistan’s President Shavkat Mirziyoyev. These agreements are not a single mining deal. They combine a political instrument with a financing-and-structuring track that is intended to yield a small set of projects that can be financed and built, and they treat processing capacity and supporting infrastructure not as optional add-ons but as core deliverables. They also provide a path for early projects to full review and financing while connecting them to longer-term offtake structures that match Washington’s newer supply-shock tools, including “Project Vault.” What the MoU Changes The MoU’s immediate purpose is to align government priorities for critical minerals across the value chain while setting expectations that will later shape which financing and partners are feasible. The press agency of Uzbekistan’s foreign ministry emphasized “responsible partnership” and “long-term development” as part of the public framing, placing governance and reputational risk on the same plane as the geological givens. The MoU also leaves several items deliberately unresolved in public form. These include project annexes, deposit designations, and operational timelines. That document design-choice pushes the next phase of bilateral cooperation into working-level scoping and sequencing, where only a small number of candidate projects can be advanced into full review. At the ministerial-level meeting, Washington clarified why it was framed as supply-chain security rather than commodity trade. Secretary of State Marco Rubio noted that critical minerals are inputs for infrastructure, industry, and defense, while Vice President J.D. Vance stressed the expansion of production across partner networks. As previously reported by The Times of Central Asia, this framing is part of a broader repositioning of U.S. engagement in Central Asia, where diplomatic formats are increasingly paired with mechanisms intended to generate trackable transactions and private-sector follow-through. For Uzbekistan, what is attractive about this cooperation is the potential to convert resource endowment into a lever for industrial development, rather than treating extraction as the endpoint. President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has publicly valued the country’s underground wealth at roughly $3 trillion. He has linked rising global demand for technological minerals to the case for higher value-added activity around strategic reserves, including lithium and tungsten. The same logic supports a commercially open posture. For Tashkent’s other investors, buyers, and processing partners, Uzbekistan’s diversification toward U.S.-linked capital signals non-exclusivity. Turning the MoU Into Projects The next phase is practical. A candidate project will advance only if investors and public lenders can transparently evaluate its licensing and fiscal terms, audit its environmental and social baseline, and have confidence in enforceable contracts that provide a dispute-resolution pathway that counterparties treat as real. For processing facilities to be constructed and operated on time, reliable power, water supply, transport links, and disciplined procurement are decisive. Such an emphasis reflects Washington’s shift “from diplomacy to deals”. Implementation is a division of labor. The DFC can facilitate private capital’s participation by structuring transactions and absorbing specific risks. The Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM) can complement those efforts through procurement-linked and exporter-linked support where the deal design fits its mandate. The bilateral investment platform is the channel that will turn candidate projects into transactions with defined terms. The proposed joint holding company is a possible co-ownership vehicle; however, capitalization, governance, and project-selection rules are not yet public. The first tranche needs a simple selection logic. Projects with credible resource definition and studies that can be updated will be closest to feasibility. Next comes the identification of a plausible path from mined output to refined products that meet buyer specifications under auditable operating standards. Infrastructure constraints, especially power, water, and logistics, come next. Finally, projects still require long-term purchase contracts with terms that can be enforced, so locking in buyers is the last step. A small number of clusters illustrates those criteria. They are only examples, not a project list. The Koytash–Ugat tungsten belt, including deposits such as Yakhton, Sautbay, and Ingichka, is a plausible early category and aligns with U.S. Geological Survey modeling of Uzbekistan’s tungsten export potential. Lithium is a second-wave target, conditional on delineation and a workable processing route. Rare-earth and rare-metal recovery as by-products from existing uranium and copper-molybdenum flows offers yet another pathway. In these cases, earlier volumes can be unlocked through improved separation, cleaner processing, and standards upgrades, without waiting for greenfield mine timelines. Diversification Without Dependency Uzbekistan is not negotiating in a vacuum. Multiple capital pools across Central Asia now compete, with different priorities in shaping where extraction ends and where processing begins. In Washington in mid-February, a new set of signed documents confirmed definitive agreements for a major tungsten development plan in Kazakhstan. This project is tied to deep processing and led by Cove Kaz Capital Group with Tau-Ken Samruk. Europe is also building its own channel through critical raw materials cooperation and financing commitments. China remains the dominant processing power and an aggressive bidder when strategic deposits come to market. Japan and South Korea are also pursuing targeted supply security through corporate offtake and project-level partnerships, as illustrated by a Mitsubishi-linked offtake arrangement tied to Kazakhstan’s rare-metals output. In that wider context, the U.S.–Uzbekistan track is an attempt to place Uzbekistan on a non-Chinese path not just for mining but also for the midstream stages that determine where value is captured and who bears reputational risk. It is in Tashkent’s interest to use competitive pressure from other investors to raise standards and accelerate domestic capability. However, if deals become proxies for external rivalry rather than instruments of Uzbekistan's own industrial policy, then its autonomy can be eroded. The strategic question for the Central Asian states is whether they can maintain balanced diversification while turning the new attention into durable processing capacity and the transparent, credible rules that Western capital requires for committing.

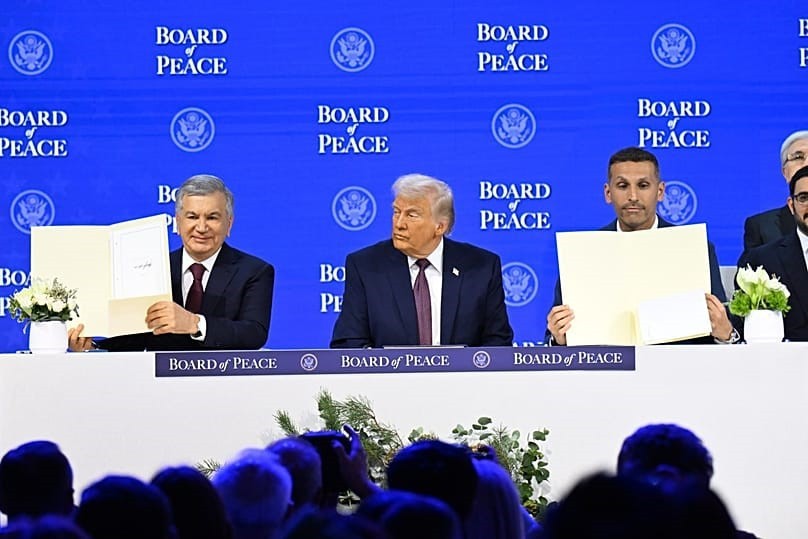

The Board of Peace and Central Asia: Asserting Agency in a Fragmented Order

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s speech at the inaugural meeting of U.S. President Donald Trump’s Board of Peace in Washington on February 19 was not only a foreign policy event, but one with significant domestic resonance. The initiatives announced include Kazakhstan’s participation in the reconstruction of Gaza, financial commitments, and readiness to send peacekeepers. Against the backdrop of economic challenges and ongoing constitutional reforms, however, a substantial segment of Kazakh society is questioning whether such an active foreign policy posture is justified at this time. The Board of Peace, the charter for which was ratified in Davos in January 2026 on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum, is positioned as an alternative to traditional multilateral institutions. According to Trump, the new body should not merely discuss conflicts, but will also "almost be looking over the United Nations and making sure it runs properly." Symbolically, the Board’s launch comes amid U.S. reductions and withholding of UN-related funding and withdrawals from multiple international bodies, alongside a partial U.S. payment toward UN arrears and the parallel creation of alternative financial and security mechanisms. According to the U.S. Mission to Kazakhstan, at the first meeting of the Board of Peace, nine members pledged a combined $7 billion aid package for the Gaza Strip. Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, the UAE, Morocco, Bahrain, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait indicated their willingness to contribute. Additionally, Trump pledged $10B in U.S. funding, framing peace and reconstruction as a strategic priority. However, experts note that these sums fall far short of projected needs. According to joint UN-EU-World Bank estimates, the full reconstruction of Gaza could require up to $70 billion. In addition, the implementation of projects is complicated by the issue of disarming Hamas, which is designated as a terrorist organization in the U.S. and the European Union. At present, there is no indication that any Western or regional government intends to revise that designation. A notable feature of the Washington summit was the synchronized participation and subsequent public statements of key member states of the Organization of Turkic States (OTS). Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Turkey effectively acted as what appeared to be an aligned geopolitical grouping, albeit without a formal declaration of joint action. What Is Kazakhstan Seeking? For Astana, participation in the Board of Peace appears to represent a renewed step in its multi-vector foreign policy doctrine. Tokayev directly stated Kazakhstan’s readiness to send medical units and observers to international stabilization forces and to allocate more than 500 educational grants for Palestinian students. In effect, Kazakhstan is reinforcing its image as a “Middle Power” prepared not only for diplomatic mediation but also for tangible contributions to international security efforts. This course aligns with the country’s existing participation in UN missions. Currently, 139 Kazakh military personnel are serving in the Golan Heights under the UN Disengagement Observer Force mandate. Nevertheless, the intensification of foreign policy engagement is raising domestic questions. Concerns voiced on social media and among experts include whether the international agenda risks diverting attention from internal economic pressures, including stagnant incomes, strain within the banking sector, and constitutional reform. Separately, speculation has circulated regarding Tokayev’s potential future candidacy for the post of UN Secretary-General. While unconfirmed, some observers interpret Kazakhstan’s visible engagement in peace initiatives as consistent with broader ambitions within multilateral diplomacy. Kazakhstan’s involvement in the Board of Peace may be understood as a long-term investment aimed at securing foreign policy dividends, including enhanced international standing, access to new economic and institutional projects, and strengthened ties with the U.S. and key actors in the Middle East. The central question remains whether Astana can maintain equilibrium between global ambitions and domestic stability. Uzbekistan: A Focus on “Soft Recovery” President Shavkat Mirziyoyev has defined a niche for Tashkent centered on civil infrastructure and social development. Uzbekistan has expressed its readiness to participate in the construction of housing, schools, kindergartens, and hospitals, while emphasizing that any external governance arrangements in Gaza must rest on the support of the local population. This approach is consistent with Uzbekistan’s recent foreign policy model: minimizing military exposure, prioritizing economic and humanitarian engagement, and strengthening its image as a responsible regional actor without direct involvement in coercive scenarios.

That positioning also reflects Tashkent’s broader engagement with Washington. In recent months, Uzbekistan has intensified negotiations with U.S. institutions, including the Export-Import Bank and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, seeking expanded financing for infrastructure, energy modernization, and industrial projects. Discussions around a bilateral Investment Platform and the reactivation of the U.S.–Uzbekistan Business Council signal a strategy focused on capital inflows and development partnerships rather than security alignment. Within that framework, participation in Gaza’s reconstruction through civil infrastructure fits comfortably into Uzbekistan’s existing diplomatic trajectory.

Azerbaijan: Political Support Without Financial Commitment

Baku has adopted a calibrated position. While Azerbaijan joined President Trump’s Board of Peace as a founding member and participated in the Washington summit, it has clarified that it does not envisage contributing to the reported $7 billion Gaza reconstruction pledge announced at the inaugural meeting.

Hikmet Hajiyev, Assistant to President Ilham Aliyev on foreign policy matters, stated that Azerbaijan supports the broader goals of stabilization and reconstruction but is not planning to allocate funds under the collective financial package referenced at the summit.

In effect, Baku has drawn a clear distinction between participation in the collective aid package and any potential project-based engagement, leaving room for future involvement without committing to the announced funding framework.

Turkey’s Expansive Role In recent months, Turkey has emerged as one of the most active and systematic actors on the Palestinian issue. Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan has declared Ankara’s readiness to operate across multiple tracks: humanitarian assistance, restoration of administrative institutions, participation in international stabilization forces, and the training of local police units. A decisive factor remains the political will of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to deploy Turkish troops to Gaza should an international consensus materialize. Currently, Turkey has signaled its readiness to contribute troops within an international stabilization framework (subject to an agreed mandate). In effect, Turkey is positioning itself as a central pillar of the initiative, capable of integrating military, administrative, and humanitarian components. The scale of Turkey’s humanitarian logistics plans is considerable, including proposals to dispatch an initial 20,000 containers of aid and mobilize numerous state and non-governmental entities. Although the Organization of Turkic States does not formally appear as a unified actor in summit documents, OTS member states constitute the most visible bloc of non-Western participants. In this light, the engagement of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Turkey in the Board of Peace appears less as a series of isolated decisions and more as part of an emerging Turkic diplomatic architecture, flexible, informal, and oriented toward pragmatic outcomes.The Language Nobody Wants to Speak About: Russian’s Uneasy Place in Central Asia’s Cultural Conversation

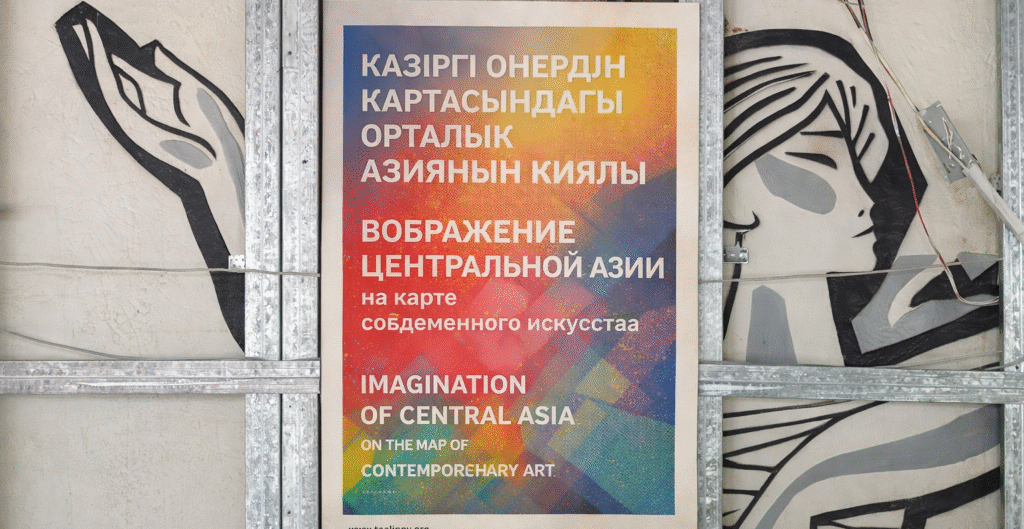

Rhetoric in segments of the Russian media has sharpened debates over sovereignty and influence across Central Asia, pushing these concerns beyond policy circles and into everyday conversations. The region is reassessing not only pipelines and alliances, but language itself. In politics, this shift is visible and symbolic. In culture, it is more difficult to discern. The Russian language still shapes how Central Asian art is funded, circulated, and institutionally processed, even as institutions distance themselves from Moscow’s influence. This contradiction sits at the heart of contemporary cultural life in the region. Artists produce work rooted in Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Tajik, or Turkmen histories. They title exhibitions in local languages. They speak passionately about decolonial futures and cultural sovereignty. But when the catalogue is written, the grant application submitted, or the curatorial text sent abroad, the language quietly shifts. First to Russian, sometimes to English, and only occasionally does it remain in the local language. This is not nostalgia, but a structural inheritance. Russian remains the shared professional language of much of the urban cultural sector. Edward Lemon, President of the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, argues that the language’s endurance reflects both ideology and pragmatism. “While local languages have become much more widespread as the Central Asian republics have strengthened their nationhood and as there has been an increase in anti-Russian sentiments since the invasion of Ukraine, Russian language use remains widespread,” Lemon told TCA. “Despite the ideological imperative to reduce reliance on Russian, there are some pragmatic reasons why it remains prominent. High levels of migration to Russia, particularly from Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan, mean that a basic competence in the language is essential to survival for many Central Asians. Russian remains a language of interethnic communication, particularly in Kazakhstan, where ethnic Russians, for the most part, are reluctant to speak Kazakh. While English has become more widespread and some of the Central Asian languages are mutually intelligible, Russian retains a status as a diplomatic, business, and civil society language for those working in multiple countries. Russia also remains a language of education. Over 200,000 Central Asians study in Russia, by far the largest destination in the world. Russian-language schools remain prominent at every level in Central Asia, from kindergarten to graduate schools. In short, while the usage of Russian is in slow decline, its position is relatively entrenched.” For cultural institutions, this reality means that distancing from Moscow politically does not automatically sever the linguistic infrastructure through which grants are written, exhibitions travel, and contracts are signed. Naima Morelli, an arts writer focused on contemporary art across Asia-Pacific and the Middle East, argues that the issue is less about elimination than coexistence. “For me, it makes sense that Russian continues to function as a practical operating language across Central Asia’s cultural infrastructure, as an inherited connective tissue of sorts. In the hypothesis of getting rid of it, the most obvious alternative for a shared language for exchanges across countries in Central Asia is English, which the global art world - in Central Asia as elsewhere - already widely employs and often considers more ‘neutral.’ But is any language truly neutral? As I see it, English carries its own hierarchies of power,” Morelli told TCA. “Of course, Russian does not bear the same perceived neutrality. The colonial legacy the Russian language carries is, in fact, addressed in the work of many Central Asian artists. Carrying something from the past, even something tied to a painful history, can still be productive and somewhat enriching, if we are able to repurpose it. We can see it clearly in Soviet architecture, so why not in the language? I think that instead of erasing Russian altogether, what would be ideal – albeit not so easy to achieve – is a polyphony: a cultural field where Kazakh, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, Russian, and English coexist, and are used depending on the context, reflecting what is the extremely layered identity of the region today.” Beyond institutional circles, however, the position of the Russian language has gradually weakened, particularly among younger generations educated primarily in national languages. In parts of the region, especially Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, its role in schooling and public life has narrowed, while English increasingly attracts urban youth seeking international opportunity. Yet for many artists, Russian is simply the most efficient way to be legible. National languages are emotionally central, but institutionally uneven. Terminology for contemporary art, critical theory, conservation, or curatorial practice is often underdeveloped, inconsistently translated, or unfamiliar to decision makers. Writing a proposal in Kazakh or Uzbek can feel like an act of cultural assertion, but also a risk. Russian offers precision, shared references, and the assurance that a jury will understand exactly what is being proposed. English occupies a different position. It is the primary language of global art markets, biennials, international foundations, and increasingly of youth. But the level of fluency required for contract negotiations, conceptual writing, and institutional correspondence remains limited to a relatively small cohort of artists and administrators. For those who possess it, English can function as a passport. This produces a quiet linguistic ladder that few institutions openly acknowledge. Local languages serve identity and symbolism. Russian underpins operation and legitimacy. English delivers visibility and international validation. The uncomfortable truth is that ascending this hierarchy often determines who is seen, funded, or invited abroad. The consequences of this system become clearest when language policies change. When institutions announce a switch away from Russian towards national languages, the move is usually framed as progressive and overdue. But access does not expand evenly. Older audiences educated in Soviet or early post-Soviet systems often lose their ability to engage with contemporary exhibitions. Independent artists from rural regions, who rely on Russian as a professional lingua franca, can find themselves cut off from institutional conversations that now presume fluency in a standardized national language they may not fully command. These tensions are not abstract. In Uzbekistan, Alisher Qodirov, a member of parliament, recently criticized the continued dominance of Russian in public services and education, arguing that reliance on Russian language schools and administration undermines the status of Uzbek as the state language and weakens cultural sovereignty. This reflects a broader regional discomfort: even where national languages are legally prioritized, Russian often remains embedded in institutional practice and professional life. The friction lies not between culture and politics, but between symbolism and administrative reality. Grant cycles and exhibition seasons, which often launch in February and March, are where these tensions surface most clearly. Calls for proposals quietly specify language requirements. In many cases, applications, correspondence, and legal contracts continue to default into Russian. Contracts are drafted in Russian legal language, even when public-facing mission statements emphasize linguistic revival and cultural sovereignty. The gap is rarely acknowledged publicly. The region operates in pragmatic multilingualism. Decolonization is the rhetoric; institutions remain bilingual or trilingual, and international correspondence often defaults to English. Language shapes authority. The language of funding and evaluation determines which narratives travel. National languages are visible in culture but are still consolidating their role in contracts, critiques, and institutional power. Russian is declining symbolically, but operationally persistent.

From Security Threat to Economic Partner: Central Asia’s New ‘View’ of Afghanistan

Afghanistan is quickly becoming more important to Central Asia, and the third week of February was filled with meetings that underscored the changing relationship. There was an “extraordinary” meeting of the Regional Contact Group of Special Representatives of Central Asian countries on Afghanistan in the Kazakh capital Astana. Also, a delegation from Uzbekistan’s Syrdarya Province visited Kabul, and separately, Uzbekistan’s Chamber of Commerce organized a business forum in the northern Afghan city of Mazar-i-Sharif. A Peaceful and Stable Future for Afghanistan The meeting in Astana brought together the special representatives of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for Afghanistan. The group was formed in August 2025. There was no explanation for why the fifth Central Asian country, Turkmenistan, chose not to participate. The purpose of the Astana meeting was to coordinate a regional approach to Afghanistan. Comments made by the representatives showed Central Asia’s changing assessment of its southern neighbor. Kazakhstan’s special representative, Yerkin Tokumov, said, “In the past [Kazakhstan] viewed Afghanistan solely through the lens of security threats… Today,” Tokumov added, “we also see economic opportunities.” Business is the basis of Central Asia’s relationship with the Taliban authorities. Representatives noted several times that none of the Central Asian states officially recognizes the Taliban government (only Russia officially recognizes that government). But that has not stopped Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, in particular, from finding a new market for their exports in Afghanistan. Uzbekistan’s special representative, Ismatulla Ergashev, pointed out that his country’s trade with Afghanistan in 2025 amounted to nearly $1.7 billion. Figures for Kazakh-Afghan trade for all of 2025 have not been released, but during the first eight months of that year, trade totaled some $335.9 million, and in 2024, amounted to $545.2 million. In 2022, Kazakh-Afghan trade reached nearly $1 billion ($987.9 million). About 90% of trade with Afghanistan is exports from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. For example, Kazakhstan is the major supplier of wheat and other grains to Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan is the biggest exporter of electricity to Afghanistan. Kyrgyzstan’s trade with Afghanistan is significantly less, but from March 2024 to March 2025, it came to some $66 million. To put that into perspective, as a bloc, the Central Asian states are now Afghanistan’s leading trade partner, with more volume than Pakistan, India, or China. Kazakhstan’s representative, Tokumov, highlighted Afghanistan’s strategic value as a transit corridor that could open trade routes between Central Asia and the Indian Ocean. Kyrgyzstan’s representative, Turdakun Sydykov, said the trade, economic, and transport projects the Central Asian countries are implementing or planning are a “key condition for a peaceful and stable future for Afghanistan and the region as a whole.” The group also discussed humanitarian aid for Afghanistan. All four of these Central Asian states have provided humanitarian aid to their neighbor since the Taliban returned to power in August 2021. Regional security was also included on the agenda in Astana, but reports offered little information about these discussions. A few days before the opening of the meeting in Astana, Russian Ambassador to Kyrgyzstan Sergei Vakunov spoke about the airbase in Kant, Kyrgyzstan, used by the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Vakunov said the base was capable of handling any “security threat to member states along the southern flank.” Vakunov was almost certainly referring to Tajikistan, which is the southern flank of the CSTO and shares a 1,350-kilometer border with Afghanistan. Since last summer, there have been several deadly clashes along a section of the Tajik-Afghan border, including two incidents that left at least five Chinese workers in the area dead. Tajikistan’s Counter-Narcotics Agency reported in early February that drug interdiction efforts along the border with Afghanistan in 2025 led to the seizure of 2.742 tons of narcotics, more than 50% higher than in 2024. The other Central Asian countries, including Turkmenistan, have engaged with the Taliban leadership since the first days after the group’s return to power. Tajikistan has taken a slower, cautious path in its relations and remains the only country in Central Asia where the ambassador from the Ashraf Ghani government that preceded the Taliban is still occupying the embassy. However, the Afghan consulate in the eastern Tajik border town of Khorog is staffed by Taliban representatives. Tajikistan’s embassy in Kabul remains open, and the Tajik ambassador met with Taliban Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi at the start of February to discuss border security. The presence of the Tajik representative at the Astana meeting is a further encouraging sign that Tajikistan is joining with its Central Asian neighbors to create a common policy toward Afghanistan. Business with Uzbekistan A delegation from Uzbekistan’s Syrdarya Province visited Kabul for a February 16-18 business forum. Syrdarya Governor Erkinjon Turdimov led the delegation. Deputy advisor to the Uzbek president, also director of the International Institute for Central Asia, Javlon Vahabov, was also there. The Uzbek delegation met with several top Taliban officials, including Foreign Minister Muttaqi and Minister of Industry and Trade Nuriddin Azizi. Governor Turdimov also met with the governor of Afghanistan’s northern Balkh Province, Muhammad Yusuf Wafa, to discuss trade. Balkh is the only Afghan province that directly borders Uzbekistan. Wafa is becoming a point man for the Taliban’s relations with Central Asia. The Balkh governor visited Tajikistan in October 2025 and met with Tajik security chief Saymumin Yatimov. The forum ended with Uzbek and Afghan representatives signing 25 deals worth some $300 million. The agreements covered “construction, food products, agriculture, furniture production, textiles, and pharmaceutical cooperation.” The provincial capital of Balkh is Mazar-i-Sharif. Uzbekistan’s Chamber of Commerce brought together more than 150 Afghan businessmen and representatives from more than 50 companies from Uzbekistan for a business forum in Mazar-i-Sharif, also conducted from February 16-18. Preliminary agreements worth potentially more than $200 million were signed. A Window of Opportunity The Central Asian states share the goals of increasing trade with Afghanistan and opening up routes through that country that connect them to Pakistani ports on the Arabian Sea. Afghanistan’s northern neighbors are also well aware that security and stability in Afghanistan are important in Central Asia. Since the five Central Asian countries became independent in late 1991, they have been contending with instability and uncertainty along the southern border. The situation in Afghanistan currently, while far from ideal, is nonetheless the most stable it has been in all the years of independence in Central Asia. Figures for Kazakh-Afghan and Uzbek-Afghan trade demonstrate for all of Central Asia the potential of engaging with Afghanistan.

China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan Railway: What It Means for Central Asia

The China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan railway (CKU railway), also known as the Kashgar–Andijan railway line, is more than an infrastructure project. It represents a geopolitical initiative that could significantly shape the future of Central Asia.

In June 2024, Beijing, Bishkek, and Tashkent signed the intergovernmental agreement to move the project forward. The project’s financing—estimated at $4.7 billion—was finalized in December 2025, sparking optimism in all three nations about regional connectivity, trade, and economic growth. Once completed, the railway is expected to become a vital strategic asset in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

From China’s perspective, the CKU project is a strategic line that diversifies its trade channels and strengthens overland access to Central Asia and beyond. Construction was ceremonially launched on 27 December 2024 in Kyrgyzstan, with major works progressing through 2025, including key tunnel works. For Uzbekistan, the railway could serve as a key link for commerce and transit. Tashkent aims to integrate the China–Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan line with existing international transport networks, including connections through Iran and Turkey. But how important is the project for Kyrgyzstan, through which, according to recent reporting, 304 km of the line will pass?

According to Nurbek Satarov, Presidential Envoy in the Naryn Region, the project is vital for Kyrgyzstan’s most mountainous region, as roughly 90% of the route through the country will run through Naryn. As he told The Times of Central Asia, construction is in full swing, and the railway is expected to be completed between 2028 and 2030, despite the challenging terrain and technical difficulties.

The project includes the construction of 50 bridges and 29 tunnels, underscoring the significant engineering complexities involved. But while regional and national authorities anticipate direct economic benefits from the project, critics argue that Kyrgyzstan may end up serving primarily as a transit country, with limited gains for the local economy. They also question the financial sustainability of the project, noting that it is backed by a long-term loan package of approximately $2.3 billion from Chinese banks. The financing, structured over 35 years and to be repaid by the joint venture company implementing the railway, increases Kyrgyzstan’s exposure to China-linked debt and has raised concerns about future repayment obligations.

[caption id="attachment_44216" align="aligncenter" width="1536"] Site visit at the road construction project in the Naryn Oblast; image: TCA, Nikola Mikovic[/caption]

However, Edil Baisalov, Kyrgyzstan’s Deputy Prime Minister, claims that the CKU will have a positive impact on the country’s economic development.

“This railroad will virtually transform Kyrgyzstan – and not just Kyrgyzstan, but the whole of Central Asia,” he told The Times of Central Asia.

Baisalov believes that the CKU railway, once completed, will be part of a larger transcontinental railroad that will cut transit times by at least seven days compared to the northern routes of the Trans-Siberian Railway and maritime transport.

The CKU line could indeed bypass the usual northern rail routes through Russia and Kazakhstan, taking a significant share of freight from those countries and reducing their transit revenue. Kyrgyzstan, on the other hand, hopes to see direct gains from the project.

“Even under the most pessimistic scenarios, the cargo loads expected to transit this route could generate at least $300 million in annual revenue, benefiting the country significantly,” Baisalov emphasized, pointing out that the CKU railway will help Kyrgyzstan increase exports of its natural resources.

As he explains, the Naryn region is rich in coal, iron, aluminum, and rare earth elements, but these resources remain largely untapped because there is no railway to transport them efficiently.

“Our mineral deposits are world-class. During the Soviet era, Kyrgyzstan’s mineral base was largely ignored in favor of deposits elsewhere. The Soviets focused only on uranium here, which was used for their first nuclear bomb, but otherwise, industrial development was minimal. As a result, Kyrgyzstan remained mostly agrarian, producing meat, wool, cotton, and tobacco. Now, with this railway, the country’s mountainous wealth can finally be accessed,” Baisalov stressed, adding that the CKU project will serve not only to export raw materials but also to support the construction of metallurgical plants, steel mills, aluminum facilities, and other industrial enterprises.

He maintains that Kyrgyzstan’s ample energy capacity positions it well for industrial expansion. Despite the global transition in energy use, he believes demand for iron, aluminum, and other key industrial metals is likely to remain strong. Moreover, in his view, the railway will reshape not only Kyrgyzstan’s trade flows but also the country’s entire economic landscape.

“The railroad will also stimulate manufacturing and logistics. International investors are already building logistics centers and assembly facilities along the line, leveraging the region’s labor force. Several towns will develop along the transcontinental railway, with direct access to markets in Europe, the Middle East, China, and Southeast Asia,” Baisalov concluded.

At present, routes from China to Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan rely on transit through Kazakhstan’s rail network, as there is no direct rail link from the People’s Republic to either country. Once completed, the project will, at the very least, enhance regional connectivity. However, the extent to which it delivers financial benefits to Kyrgyzstan will likely depend on transit volumes, tariff policies, and the country’s ability to develop complementary industries along the route.

Site visit at the road construction project in the Naryn Oblast; image: TCA, Nikola Mikovic[/caption]

However, Edil Baisalov, Kyrgyzstan’s Deputy Prime Minister, claims that the CKU will have a positive impact on the country’s economic development.

“This railroad will virtually transform Kyrgyzstan – and not just Kyrgyzstan, but the whole of Central Asia,” he told The Times of Central Asia.

Baisalov believes that the CKU railway, once completed, will be part of a larger transcontinental railroad that will cut transit times by at least seven days compared to the northern routes of the Trans-Siberian Railway and maritime transport.

The CKU line could indeed bypass the usual northern rail routes through Russia and Kazakhstan, taking a significant share of freight from those countries and reducing their transit revenue. Kyrgyzstan, on the other hand, hopes to see direct gains from the project.

“Even under the most pessimistic scenarios, the cargo loads expected to transit this route could generate at least $300 million in annual revenue, benefiting the country significantly,” Baisalov emphasized, pointing out that the CKU railway will help Kyrgyzstan increase exports of its natural resources.

As he explains, the Naryn region is rich in coal, iron, aluminum, and rare earth elements, but these resources remain largely untapped because there is no railway to transport them efficiently.

“Our mineral deposits are world-class. During the Soviet era, Kyrgyzstan’s mineral base was largely ignored in favor of deposits elsewhere. The Soviets focused only on uranium here, which was used for their first nuclear bomb, but otherwise, industrial development was minimal. As a result, Kyrgyzstan remained mostly agrarian, producing meat, wool, cotton, and tobacco. Now, with this railway, the country’s mountainous wealth can finally be accessed,” Baisalov stressed, adding that the CKU project will serve not only to export raw materials but also to support the construction of metallurgical plants, steel mills, aluminum facilities, and other industrial enterprises.

He maintains that Kyrgyzstan’s ample energy capacity positions it well for industrial expansion. Despite the global transition in energy use, he believes demand for iron, aluminum, and other key industrial metals is likely to remain strong. Moreover, in his view, the railway will reshape not only Kyrgyzstan’s trade flows but also the country’s entire economic landscape.

“The railroad will also stimulate manufacturing and logistics. International investors are already building logistics centers and assembly facilities along the line, leveraging the region’s labor force. Several towns will develop along the transcontinental railway, with direct access to markets in Europe, the Middle East, China, and Southeast Asia,” Baisalov concluded.

At present, routes from China to Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan rely on transit through Kazakhstan’s rail network, as there is no direct rail link from the People’s Republic to either country. Once completed, the project will, at the very least, enhance regional connectivity. However, the extent to which it delivers financial benefits to Kyrgyzstan will likely depend on transit volumes, tariff policies, and the country’s ability to develop complementary industries along the route.

Sunkar Podcast

Central Asia and the Troubled Southern Route