Pannier and Hillard’s Spotlight on Central Asia: New Episode Available Sunday

As Managing Editor of The Times of Central Asia, I’m delighted that, in partnership with the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, from October 19, we are the home of the Spotlight on Central Asia podcast. Chaired by seasoned broadcasters Bruce Pannier of RFE/RL’s long-running Majlis podcast and Michael Hillard of The Red Line, each fortnightly instalment will take you on a deep dive into the latest news, developments, security issues, and social trends across an increasingly pivotal region. This week, the team is taking a deep dive into the worsening situation for Central Asian migrant laborers in Russia, as seen in the recent raid in Khabarovsk, where one Uzbek citizen was beaten to death, and another was left in a coma. Our guest is Tolkun Umaraliev, the regional director for RFERL's Central Asian service and previously the head of RFERL's Migrant Media project.

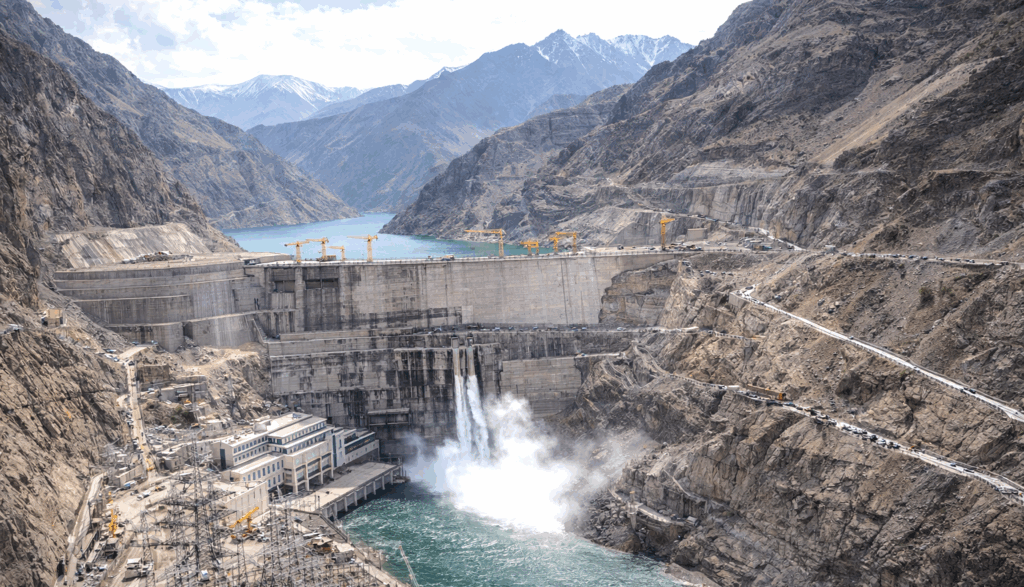

Independent Audit Raises Concerns Over Financial Reporting at Tajikistan’s Rogun Hydropower Plant

An independent audit of Tajikistan’s flagship Rogun Hydropower Plant (HPP) has flagged serious financial reporting concerns, including a possible understatement of the company’s share capital. The findings, cited by Asia-Plus from the auditor’s conclusion, point to broader risks in the management of one of Central Asia’s most ambitious infrastructure projects. The audit, covering Rogun’s 2024 financial statements, was conducted by Baker Tilly Tajikistan, a registered member of the international Baker Tilly network. The auditors issued a qualified opinion, meaning they were unable to fully confirm the accuracy of the company’s accounts and highlighted several material issues. The audited report has been published on the official Rogun HPP website. Among the key concerns, auditors stated they had not been involved in scheduled or annual inventories of cash, fixed assets, or other inventories as of December 31, 2024. This limited their ability to verify the existence and condition of parts of the company’s assets through alternative procedures, raising the risk of potential misstatements in the financial records. The audit also noted that Rogun’s fixed assets had not been revalued in recent years, despite signs that their book value may significantly differ from their fair market value. Under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), such assets are required to be revalued periodically. The failure to do so may distort the company’s true financial position. A particularly striking finding involved discrepancies in the company’s reported share capital. Rogun’s financial statements list share capital at 40.03 billion somoni, while the Unified State Register of Legal Entities records it at 45 billion somoni. The difference, 4.97 billion somoni, or approximately $540 million, may indicate that the company has understated its equity. According to the audit, Rogun’s management did not provide adequate documentation to support the lower figure. As of the end of 2024, Rogun reported total assets of 49.48 billion somoni, up from the previous year. The bulk, 35.33 billion somoni, was classified as construction in progress, reflecting the plant’s ongoing development phase. The book value of fixed assets stood at 9.28 billion somoni, with most 2024 expenditures directed toward equipment and construction work. The company reported 2024 revenues of 258.4 million somoni, primarily from electricity sales. However, operating costs exceeded income, totaling 367.4 million somoni, resulting in a net loss of 277.3 million somoni. This marks a modest improvement over 2023, when the net loss was 332.8 million somoni. The auditors described these losses as systemic, emphasizing that the plant has not yet reached full operational capacity. Despite the loss, Rogun HPP generated a positive operating cash flow of more than 3.2 billion somoni in 2024. This was largely attributed to increased liabilities from founders and settlements with state institutions. Baker Tilly stressed that the company’s continued operation depends heavily on sustained government support, which is regularly allocated through Tajikistan’s state budget. The auditors also issued a warning over material uncertainty regarding the company’s ability to continue as a going concern. However, Rogun’s management maintains that the project is a strategic national asset, vital to Tajikistan’s long-term energy security and plans for future electricity exports. With an installed capacity of 3,780 megawatts, Rogun is expected to become the largest hydropower plant in Central Asia. Once fully operational, it is projected to generate over 14.5 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity annually. The final turbine is scheduled for commissioning in 2029.

Recent Stories From Tajikistan That You May Have Missed

Hydropower strain returns as rationing tightens

A dry autumn has translated into a difficult start to winter for Tajikistan’s electricity system, with renewed restrictions tied to low reservoir levels. A recent Reuters report on rationing described a drop in water levels feeding the country’s hydropower fleet, with the reservoir at Nurek, the backbone of generation, reported to be substantially below the same point last year. The measures announced go beyond household inconvenience: restrictions have been accompanied by reduced lighting and tighter electricity allocations for public institutions, while officials explore imports and balancing arrangements with neighbors.Rogun’s mitigation narrative hardens as oversight grows

The Rogun hydropower project remains the long-term answer Dushanbe puts forward for these seasonal crunches, and also the project that draws the most intense international scrutiny. The Times of Central Asia’s coverage of Rogun’s environmental planning highlighted a shift in framing: a “no net loss” biodiversity approach, built around compensatory habitat restoration exceeding the estimated footprint of land losses. That messaging is designed to reassure lenders and stakeholders that the dam’s scale will be matched by formal safeguards, and to keep financing pathways open at a time when environmental and social governance has become central to major infrastructure underwriting. But “no net loss” is also an invitation for closer measurement, and criticism has increasingly focused on whether offsets can meaningfully address river-system impacts, not only terrestrial habitat. Advocacy briefs circulating around Rogun argue that aquatic biodiversity mitigation and downstream ecological risk remain the hardest pieces to quantify and enforce, especially on long timelines where implementation phases stretch years beyond core construction. In other words, Rogun’s external story is evolving: it is no longer only about generating electricity and exporting surplus. It is also about whether international standards can be applied credibly to a project of this size — and whether promised safeguards hold up under cross-border water politics and long-term monitoring.A border-security story triggers a rare media confrontation

If energy is the long-term strategic theme, border security remains the most sensitive. That sensitivity spilled into public view after a Reuters dispatch on alleged Tajik–Russian border talks suggested Dushanbe was considering deeper cooperation with Moscow and the CSTO for monitoring the Afghan frontier. Tajikistan’s response was unusually direct. In a sharply worded statement reported by Eurasianet’s account of the dispute, the Foreign Ministry said the report “does not correspond to reality” and insisted the border situation was under national control. Shortly afterwards, The Times of Central Asia’s report on Reuters withdrawing the story underscored how rare it is for a major international outlet to retract a piece following an official denial in the region. For Western governments, the episode illustrates how the Afghan border remains a geopolitical pressure valve, and how carefully Dushanbe manages the optics of any foreign military footprint, particularly at a time when Russia’s regional role is politically charged and China’s security profile is rising.Land degradation moves from “environmental” to “economic risk”

Finally, an issue that has long sat in the “environment” column is now being described increasingly as a macroeconomic threat: land degradation and food security. The Times of Central Asia’s summary of FAO-linked findings drew attention to estimates that a very large share of arable land is already degraded, driven by erosion, salinization and nutrient loss. International analysis has pushed the point further. In The Diplomat’s deep dive on Tajikistan’s food-security constraints, the argument is that fragmentation of farmland, limited mechanization and underinvestment in irrigation and soil management are combining with climate stress to reduce resilience, in a country where household economics, migration decisions and political stability are closely tied to rural livelihoods. Broader UN messaging, including FAO’s work on land and soils, frames the same dynamic globally: degraded land reduces yields and amplifies vulnerability to drought and extreme weather. Together, these four developments capture Tajikistan’s current trajectory: hydropower remains both the country’s strength and its exposure; Rogun is increasingly a test case for international infrastructure standards; the Afghan border remains politically combustible; and land degradation is becoming an economic headline rather than a background environmental warning.Deadly Clashes and Gold Mines Fuel Tensions on the Tajik-Afghan Border

Along a short strip of the Tajik-Afghan border, there has been a lot of activity in recent months, including the most serious incidents of cross-border violence in decades. Most of this activity has involved Tajikistan’s Shamsiddin Shohin district, a sparsely inhabited area where the population ekes out a living farming and herding in the foothills of the Pamir Mountains. Why the situation changed so suddenly is not entirely clear, but it is clear that the district is now the hot spot along the Tajik-Afghan frontier.

A Dubious Post-Independence Reputation

The Shamsiddin Shohin district is in Tajikistan’s southwestern Khatlon region. The district is located near the place where Afghan territory starts to make its northern-most protrusion. The elevation across most of the district is between 1,500-2,000 meters.

The district is about 2,300 square kilometers and has a population of some 60,000. Shuroobad, population roughly 11,000, is the district capital, and the entire district was once called Shuroobad. It was renamed Shamsiddin Shohin in 2016 to honor the Tajik poet and satirist of the late 19th century, who was born in the area.

Tajikistan and Afghanistan are divided by the Pyanj River, which further downstream merges with other rivers to become the Amu Darya, known to the Greeks as the Oxus, one of Central Asia’s two great rivers.

[caption id="attachment_41640" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] The road to Shuroobad; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

The Tajik-Afghan frontier is about 1,360 kilometers. Some 70 kilometers is the southern border of the Shamsiddin Shohin district, but it is the first area, traveling downstream, where the current of the Pyanj River slows significantly.

In the first years after the Bolshevik Revolution broke out, many Tajiks fled through what is now the Shamsiddin Shohin district into Afghanistan. Some seventy years later, thousands of Tajiks again fled through the district into Afghanistan when the newly independent state of Tajikistan was engulfed by civil war.

The United Tajik Opposition (UTO), the group fighting against the Tajik government during the 1992-1997 civil war, made frequent use of the Shamsiddin Shohin area to bring weapons from Afghanistan. UTO fighters had safe havens in Afghanistan, and they often made their way through this district, retreating south of the border and returning via the district once they were rested and resupplied.

There are only a few roads in the Shamsiddin Shohi district. The European Union funded the construction of the Friendship Bridge, which was completed in 2017, and connects the district to Afghanistan. It has often been closed by the Tajik authorities due to security concerns emanating from the Afghan side of the border.

Anyone crossing illegally from Afghanistan into the Shamsiddin Shohin district could easily hide in the rugged hills and abundance of caves in the area, making it ideal for smugglers and other intruders. Aside from a few small villages along the banks, there are no settlements for 20 to 30 kilometers north of the river.

Border posts were built during the time Tajikistan was a Soviet republic. Russian border guards remained in Tajikistan after the collapse of the USSR, and fortified these outposts as they increasingly came under attack from smugglers and UTO fighters crossing from Afghanistan.

Foreign governments funded the construction of new border guard posts along the Afghan frontier after the last Russian border guards departed in 2005. China, for example, financed the construction of the Gulhan border guard post in the Shamsiddin Shohin district in 2016.

[caption id="attachment_41639" align="aligncenter" width="2560"]

The road to Shuroobad; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

The Tajik-Afghan frontier is about 1,360 kilometers. Some 70 kilometers is the southern border of the Shamsiddin Shohin district, but it is the first area, traveling downstream, where the current of the Pyanj River slows significantly.

In the first years after the Bolshevik Revolution broke out, many Tajiks fled through what is now the Shamsiddin Shohin district into Afghanistan. Some seventy years later, thousands of Tajiks again fled through the district into Afghanistan when the newly independent state of Tajikistan was engulfed by civil war.

The United Tajik Opposition (UTO), the group fighting against the Tajik government during the 1992-1997 civil war, made frequent use of the Shamsiddin Shohin area to bring weapons from Afghanistan. UTO fighters had safe havens in Afghanistan, and they often made their way through this district, retreating south of the border and returning via the district once they were rested and resupplied.

There are only a few roads in the Shamsiddin Shohi district. The European Union funded the construction of the Friendship Bridge, which was completed in 2017, and connects the district to Afghanistan. It has often been closed by the Tajik authorities due to security concerns emanating from the Afghan side of the border.

Anyone crossing illegally from Afghanistan into the Shamsiddin Shohin district could easily hide in the rugged hills and abundance of caves in the area, making it ideal for smugglers and other intruders. Aside from a few small villages along the banks, there are no settlements for 20 to 30 kilometers north of the river.

Border posts were built during the time Tajikistan was a Soviet republic. Russian border guards remained in Tajikistan after the collapse of the USSR, and fortified these outposts as they increasingly came under attack from smugglers and UTO fighters crossing from Afghanistan.

Foreign governments funded the construction of new border guard posts along the Afghan frontier after the last Russian border guards departed in 2005. China, for example, financed the construction of the Gulhan border guard post in the Shamsiddin Shohin district in 2016.

[caption id="attachment_41639" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] A burnt-out bus in the Pyanj River between Tajikistan and Afghanistan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

New People, New Business

Illegal narcotics, weapons, precious and semi-precious stones, and a variety of contraband goods have been regularly smuggled from Afghanistan through Tajikistan since not long after Tajikistan became independent. It didn’t matter who the government in Afghanistan was. The Shamsiddin Shohin district is one of the more popular places along the Tajik-Afghan border for smugglers.

However, almost all of the recent violence along the Tajik-Afghan frontier is happening in the Shamsiddin Shohin district and Afghan territory on the other side of the river, and smuggling does not seem to be the main reason.

Not long after the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, agreements were signed with Chinese companies to develop Afghan gas and oil fields, and mineral deposits, notably gold. About three years ago, Chinese and Afghans started working at several sites in Afghanistan’s northern Badakhshan Province that borders Tajikistan.

In February 2023, the Tajik-Chinese company Zarafshan announced the discovery of new gold deposits, one of the most promising of which was in the Shamsiddin Shohin district. Zarafshan subsidiary Shohin SM started work shortly after that announcement.

In November 2024, armed men from Afghanistan crossed into Tajikistan and attacked the Shohin SM gold-mining camp, killing one Chinese worker and wounding at least four other workers, three of whom were also Chinese (the fourth was Tajik). The Tajik authorities blamed the attack on drug smugglers who wandered too close to the gold-mining camp and were seen by camp security guards.

In May 2025, the Tajik authorities apprehended a group of Chinese and Afghans who had crossed from Afghanistan on excavators into the Shamsiddin Shohin district. Tajik officials alleged the group intended to launder money, though the head of the district, Zafar Gulzoda, said the group was searching for gold scrap on the Tajik side of the Pyanj River.

Then in August 2025, Tajik border guards stationed in Shamsiddin Shohin exchanged fire with Taliban fighters on the other side of the river. The Tajik border guards did not suffer any casualties, but one Taliban fighter was killed and four others wounded. The head of the local Tajik border guards led a small detachment of troops across the border into Afghanistan for talks with local Taliban officials and the head of the local mining operation.

In late October, there were reports that Tajik border guards and the Taliban were again involved in a firefight in the same area as the shooting in August. A report from an Afghan media outlet said there were casualties on both sides, but Tajik and Taliban officials never commented on the incident.

The reason for the second exchange of fire was reportedly construction work at a Chinese-Afghan gold mining site that had altered the course of the Pyanj River and sent more water to the Tajik bank, sparking concerns about flooding in the Shamsiddin Shohin district. The Tajik authorities have complained about this several times.

Then, on November 26, three Chinese workers at the Shohin SM gold mining camp were killed and two wounded in an attack that combined gunfire and the use of a drone armed with a grenade. On the last day of November, two Chinese roadworkers were shot dead and three wounded in Tajikistan’s Darvaz district, the next district east of Shamsiddin Shohin. The shots came from the Afghan side of the river.

On December 24, Tajik border guards in Shamsiddin Shohin were again involved in a shootout, this time with an armed group that came across the river from Afghanistan. Two Tajik border guards and three of the attackers were killed in the clash. The Tajik authorities said the armed group were terrorists who attacked the Tajik border guard post in the area.

No other place along the Tajik-Afghan border has seen the sort of violence that is becoming routine in the Shamsiddin Shohin district. The alleged “smuggler” attack on the gold mining camp in November 2024, and then a series of attacks and exchanges of fire since late August 2025.

Chinese gold mining, smuggling, and terrorists are combining to make the Shamsiddin Shohin district the hot spot of Tajikistan’s border with Afghanistan.

A burnt-out bus in the Pyanj River between Tajikistan and Afghanistan; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

New People, New Business

Illegal narcotics, weapons, precious and semi-precious stones, and a variety of contraband goods have been regularly smuggled from Afghanistan through Tajikistan since not long after Tajikistan became independent. It didn’t matter who the government in Afghanistan was. The Shamsiddin Shohin district is one of the more popular places along the Tajik-Afghan border for smugglers.

However, almost all of the recent violence along the Tajik-Afghan frontier is happening in the Shamsiddin Shohin district and Afghan territory on the other side of the river, and smuggling does not seem to be the main reason.

Not long after the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, agreements were signed with Chinese companies to develop Afghan gas and oil fields, and mineral deposits, notably gold. About three years ago, Chinese and Afghans started working at several sites in Afghanistan’s northern Badakhshan Province that borders Tajikistan.

In February 2023, the Tajik-Chinese company Zarafshan announced the discovery of new gold deposits, one of the most promising of which was in the Shamsiddin Shohin district. Zarafshan subsidiary Shohin SM started work shortly after that announcement.

In November 2024, armed men from Afghanistan crossed into Tajikistan and attacked the Shohin SM gold-mining camp, killing one Chinese worker and wounding at least four other workers, three of whom were also Chinese (the fourth was Tajik). The Tajik authorities blamed the attack on drug smugglers who wandered too close to the gold-mining camp and were seen by camp security guards.

In May 2025, the Tajik authorities apprehended a group of Chinese and Afghans who had crossed from Afghanistan on excavators into the Shamsiddin Shohin district. Tajik officials alleged the group intended to launder money, though the head of the district, Zafar Gulzoda, said the group was searching for gold scrap on the Tajik side of the Pyanj River.

Then in August 2025, Tajik border guards stationed in Shamsiddin Shohin exchanged fire with Taliban fighters on the other side of the river. The Tajik border guards did not suffer any casualties, but one Taliban fighter was killed and four others wounded. The head of the local Tajik border guards led a small detachment of troops across the border into Afghanistan for talks with local Taliban officials and the head of the local mining operation.

In late October, there were reports that Tajik border guards and the Taliban were again involved in a firefight in the same area as the shooting in August. A report from an Afghan media outlet said there were casualties on both sides, but Tajik and Taliban officials never commented on the incident.

The reason for the second exchange of fire was reportedly construction work at a Chinese-Afghan gold mining site that had altered the course of the Pyanj River and sent more water to the Tajik bank, sparking concerns about flooding in the Shamsiddin Shohin district. The Tajik authorities have complained about this several times.

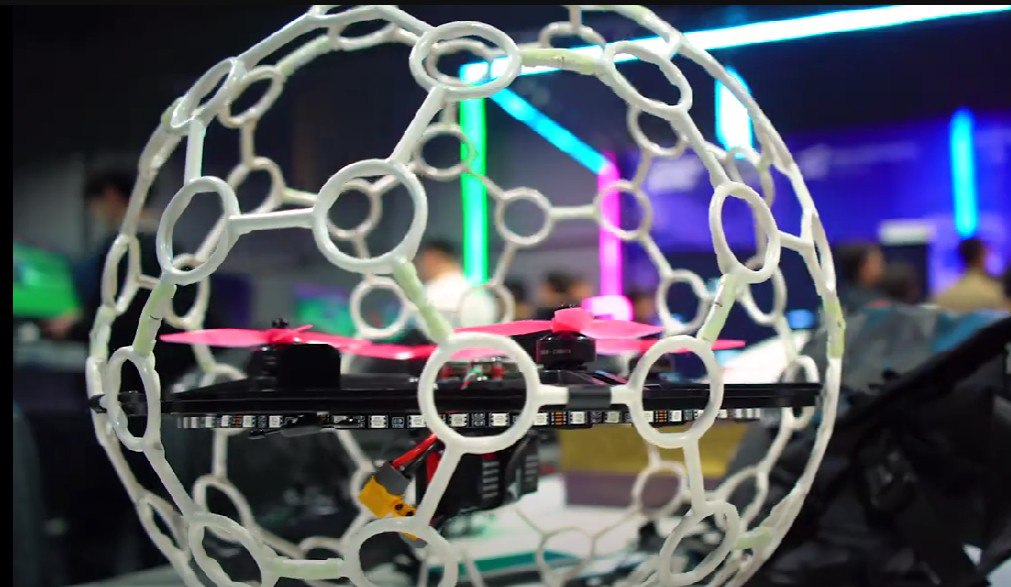

Then, on November 26, three Chinese workers at the Shohin SM gold mining camp were killed and two wounded in an attack that combined gunfire and the use of a drone armed with a grenade. On the last day of November, two Chinese roadworkers were shot dead and three wounded in Tajikistan’s Darvaz district, the next district east of Shamsiddin Shohin. The shots came from the Afghan side of the river.

On December 24, Tajik border guards in Shamsiddin Shohin were again involved in a shootout, this time with an armed group that came across the river from Afghanistan. Two Tajik border guards and three of the attackers were killed in the clash. The Tajik authorities said the armed group were terrorists who attacked the Tajik border guard post in the area.

No other place along the Tajik-Afghan border has seen the sort of violence that is becoming routine in the Shamsiddin Shohin district. The alleged “smuggler” attack on the gold mining camp in November 2024, and then a series of attacks and exchanges of fire since late August 2025.

Chinese gold mining, smuggling, and terrorists are combining to make the Shamsiddin Shohin district the hot spot of Tajikistan’s border with Afghanistan.

2025: The Year Central Asia Stepped Onto the Global Stage

For much of the post-Soviet era, Central Asia occupied a peripheral place in global affairs. It mattered to its immediate neighbors, but rarely shaped wider debates. In 2025, that changed in visible ways. The region became harder to ignore, largely not because of ideology or alignments, but because of assets that the world increasingly needs: energy, minerals, transit routes, and political access across Eurasia. One of the clearest signs came in April, when the European Union and the leaders of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan met in Samarkand for their first summit at the head-of-state level. The meeting concluded with a joint declaration upgrading relations to a strategic partnership, with a focus on transport connectivity, energy security, and critical raw materials. The document marked a shift in how Brussels views Central Asia, moving beyond development assistance toward geopolitical cooperation, as outlined in the official EU–Central Asia summit joint declaration. European interest is rooted in necessity. Russia’s war in Ukraine has forced EU governments to rethink energy imports, supply chains, and overland trade routes. Central Asia sits astride the most viable alternatives that bypass Russian territory. It also holds resources essential to Europe’s green transition, including uranium and a range of industrial metals. The region’s leaders spent much of the year framing their diplomacy around these tangible advantages, rather than abstract political alignments. The United States followed a similar track. Through the C5+1 format, Washington deepened engagement with all five Central Asian states, with particular emphasis on economic cooperation and supply-chain resilience. A key element has been the Critical Minerals Dialogue, launched to connect Central Asian producers with Western markets. This initiative formed part of a broader U.S. effort to diversify access to strategic materials and reduce dependence on Russia and China. Russia remained a central but changing presence in Central Asia throughout 2025. Economic ties, labor migration, and shared infrastructure ensured that Moscow continued to matter across the region. At the same time, however, Russia’s war in Ukraine constrained its ability to act as the dominant external power it once was. Central Asian governments maintained pragmatic relations with Moscow, but they increasingly treated Russia as one partner among several rather than the default reference point. Trade continued, security cooperation persisted, and political dialogue remained active, yet the balance shifted toward hedging rather than dependence. Uranium sits at the center of this shift, with the United States having banned imports of certain Russian uranium products under federal law, with waivers set to expire no earlier than January 1, 2028. As Washington restructures its nuclear fuel supply chain, Central Asia’s role has grown sharply. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s 2024 Uranium Marketing Annual Report, Kazakhstan supplied 24% of uranium delivered to U.S. reactor operators, while Uzbekistan accounted for about 9%. Canada and Australia remain major suppliers, but the Central Asian share is now strategic rather than marginal. That economic weight translated into political visibility. In December, U.S. President Donald Trump said he would invite Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to attend the U.S.-hosted G20 summit in 2026. While guest invitations do not confer membership, they offer access to senior leaders and investors at a critical moment in global supply-chain restructuring. This move is part of a broader U.S. effort to expand engagement with Central Asia. The region’s growing global presence was also reflected beyond diplomacy, from Uzbekistan’s qualification for the 2026 football World Cup to increased international media attention on Central Asian economies, reform agendas, societies, and infrastructure projects. Investment trends reinforced the political signals. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development reported record investment in Central Asia – including Mongolia - committing nearly €2.26 billion across 121 projects, with Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan receiving the largest shares. The EBRD described the surge as driven by infrastructure, energy, and private-sector development. Mongolia’s growing inclusion reflects a wider regional pull, with Ulaanbaatar stepping up engagement with its Central Asian neighbors through trade, transport cooperation, and multilateral investment initiatives. Energy security was not limited to nuclear fuel. Hydropower returned to the regional agenda in 2025, especially in discussions around Kyrgyzstan’s long-delayed Kambarata-1 project. The dam, with a planned capacity of 1,860 megawatts, is seen as critical for stabilizing electricity supply across parts of Central Asia. It was reported that the EBRD could consider lending up to $1.5 billion for the project, underscoring how regional infrastructure is now tied to international financing and diplomacy. Regional cooperation among the five Central Asian states also deepened, with leaders increasingly coordinating on water management, energy sharing, and cross-border transport rather than addressing these issues in isolation. Security concerns also shaped the year. Violence along the Tajikistan-Afghanistan border, including attacks near sites employing Chinese nationals, exposed the region’s vulnerability to instability spilling over from Afghanistan. The incidents prompted warnings from Beijing and renewed scrutiny of border security in Central Asia. The Times of Central Asia has reported on the situation as part of a wider examination of how insecurity affects foreign investment and regional stability. China’s role in Central Asia stayed substantial and highly visible. Beijing remained the region’s largest single trading partner and a key investor in infrastructure, mining, and energy projects. In 2025, however, Chinese engagement also faced sharper scrutiny, with the risks that accompany China’s deep economic footprint increasingly highlighted. For Central Asian governments, the challenge was to preserve Chinese investment while asserting greater control over security and diversification. The result was not a retreat from China, but a more cautious and negotiated engagement. Despite these risks, Central Asian governments resisted pressure to align exclusively with any single power. Instead, they pursued a strategy of increasing diversification. The EU, the United States, China, and Russia all remained engaged, but none dominated the region’s external agenda. Ties with Azerbaijan also deepened in 2025, driven by shared interests in transport, energy, and westward connectivity. Baku emerged as a key partner in linking Central Asia to the South Caucasus and onward to European markets, particularly through Caspian transit routes. This cooperation increasingly took shape within the C6+1 framework, which brings Azerbaijan together with the five Central Asian states to coordinate infrastructure planning, trade facilitation, and regional connectivity. This underscored a growing recognition that Central Asia’s global role depends not only on internal links, but on reliable Western gateways. Turkmenistan, traditionally cautious in its diplomacy, also expanded engagement around energy exports and transport links across the Caspian, reinforcing its role in regional connectivity. Japan played a quieter but increasingly consistent role in Central Asia in 2025. Tokyo focused on economic cooperation, infrastructure financing, and technical assistance, often emphasizing transparency and long-term sustainability. Japanese engagement carried less geopolitical weight than that of larger powers, but it offered Central Asian states another option for diversification. Japan’s steady presence reinforced the region’s ability to widen its external partnerships without triggering strategic friction. This approach gave Central Asian states greater leverage and reduced their exposure to shifts in any one relationship. Whilst 2025 may not have been a decisive turning point, it was a clear step. The region did not suddenly acquire global influence, but it increasingly demonstrated why it matters on a global stage. Strategic documents, investment flows, and energy data all point to the same conclusion: Central Asia entered the year as a subject of geopolitical discussion, and ended it as a participant. Whether that momentum continues will depend on execution. Summits must continue to turn into contracts, and contracts into infrastructure and industry. For now, the direction is unmistakable. In 2025, Central Asia stepped onto the global stage not by seeking attention, but by offering what the world increasingly needs.

Rising Border Insecurity Puts Chinese Interests at Risk in Tajikistan

Mounting insecurity along the Tajikistan-Afghanistan border is increasingly threatening Chinese interests and heightening Beijing’s concerns about regional stability, Al Jazeera has reported, citing recent incidents and official statements from Dushanbe. According to the report, the Tajik authorities have recorded multiple armed infiltrations from Afghan territory in recent months, resulting in more than a dozen deaths. Among the victims were five Chinese nationals working on infrastructure and mining projects in remote areas of Tajikistan. The attacks reportedly targeted Chinese companies and personnel specifically, prompting alarm in Beijing. Al Jazeera noted that China is Tajikistan’s largest creditor and one of its most significant economic partners. Chinese firms have a major presence in road construction, infrastructure, and extractive industries, many of which are situated near the porous Afghan border. The growing threat of violence has raised serious concerns among Chinese officials about the safety of their citizens and investments. Tensions escalated dramatically on November 26, when a drone strike hit a Chinese-operated gold-mining facility, and gunfire targeted workers at a state-owned enterprise. Several Chinese nationals were reportedly killed in the coordinated attacks. In response, the Chinese embassy in Dushanbe advised Chinese citizens and enterprises to withdraw from border areas and called on Tajik authorities to take “all necessary measures” to protect Chinese nationals and assets. Citing regional analysts, Al Jazeera reported that although no group has claimed responsibility, the tactics are consistent with those used by Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP). Analysts believe ISKP is attempting to undermine the Taliban’s claims of providing security by deliberately targeting foreign nationals, particularly Chinese workers. Tajik officials described the incidents as evidence of the Taliban’s “irresponsibility” and repeated failure to deliver on its international commitments. Dushanbe has demanded an official apology and concrete guarantees regarding border security. Most of the recent attacks, according to Tajik authorities, have originated from Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province, a complex and fragile security zone. The Taliban’s crackdown on poppy cultivation, which has provoked resentment among local farmers, is believed to have further destabilized the area. The Taliban have expressed regret over the incidents, blamed unspecified non-state actors, and insisted that Afghanistan poses no threat to neighboring countries. They reaffirmed their commitment to the Doha Agreement and regional stability. In December, Tajikistan’s State Committee for National Security (SCNS) reported another armed incident on the southern frontier. According to the SCNS, three armed individuals crossed into Tajik territory late on December 23 and attempted to attack a border post in the Shamsiddin Shohin district. The intruders, who refused to surrender, were killed in a firefight. Two Tajik border guards also died in the clash, underscoring the persistent volatility along the border.

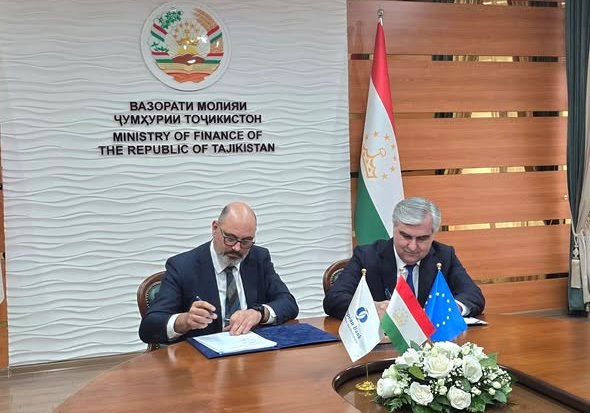

Japan and Central Asia Enter a New Era of Strategic Partnership

On December 20, the first summit of Central Asian and Japanese leaders (CA+JAD) was held in Tokyo. The Tokyo Declaration, an ambitious roadmap for future cooperation, was adopted during the summit. It aims to transform relations between Japan and the five Central Asian countries into a deep and multifaceted strategic partnership. New Paths for the Region Japan intends to invest about $20 billion in business projects across Central Asia over the next five years. Priority areas for cooperation include environmental initiatives, and the transition to carbon neutrality in the energy sector. Additional areas include developing supply chains for key minerals, disaster risk reduction, and earthquake preparedness. Projects in agriculture and logistics, particularly improvements along the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, were also discussed. Other topics covered included launching direct flights between Japan and Central Asia, advancing cooperation in digital technologies and artificial intelligence, and expanding scholarships and training programs. Attendees included Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi; Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev; Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov; Tajik President Emomali Rahmon; Turkmen President Serdar Berdimuhamedov; and Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev. The second Central Asia-Japan summit is scheduled to take place in Kazakhstan, in line with the agreed English alphabetical rotation. Turkmenistan: Petrochemical Cooperation President Serdar Berdymuhamedov met with representatives of major Japanese corporations, including Sumitomo, Toyo Engineering, Muroosystems, Itochu, Argonavt, Mitsubishi, Kawasaki Heavy Industries, and Tokyo Boeki Eurasia. He cited several successful Japanese-led projects in Turkmenistan, such as waste processing plants, a wastewater treatment initiative for industrial reuse, PET plastic recycling, and e-waste processing to reduce hazardous materials. New memorandums were signed between Turkmen and Japanese entities. Key among them: an agreement involving the state-owned concern Turkmenhimiya, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Mitsubishi Corporation, and Gap Inşaat on building a urea plant in the Balkan region with a capacity of 1.155 million tons per year. Turkmenhimiya also signed an agreement with Kawasaki Heavy Industries to extend maintenance for the Akhal gas-to-gasoline plant. In addition, a cooperation deal was reached with Toyo Engineering and Turkey’s Rönesans Endüstri for the second phase of the Kiyanly polymer plant. Other memoranda included partnerships between the Ministry of Automobile Transport of Turkmenistan and Sumitomo Corporation, TurkmenGas and Sumitomo Europe, and the Ministry of Communications and Mitsubishi Corporation Machinery, focusing on artificial intelligence and digital technologies. Agreements were also signed with media outlets, banks, and universities. Diplomatic ties between Japan and Turkmenistan were established in 1992. The Japanese Embassy opened in Ashgabat in 2005, and the Turkmen Embassy in Tokyo followed in 2013. Japan also plays a vital role in Turkmenistan’s export of polypropylene. Japanese firms Kawasaki and Sojits helped construct a fertilizer complex in the town of Mary, while Itochu and Day Nippon were involved in modernizing the national railway’s IT systems. Kyrgyzstan: Energy and Education Ties President Sadyr Japarov oversaw the signing of bilateral agreements spanning exports, energy, healthcare, education, tourism, agribusiness, and digital development. Agreements included a roadmap between Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Energy and MurooSystems for a small hydropower plant on the Chon-Kemin River and various education-related memorandums with Japanese firms like Sprix, Fujifilm SystemService, Digital Knowledge Inc, and Gakken Holdings. A strategic memorandum of understanding was signed between the Kyrgyz-Japanese Human Development Center (KRJC) and the Kyrgyz-Japanese School Complex. Another focused on establishing the Kyrgyz-Japanese Digital University (K-JDU). Uzbekistan: Strategic Investment Expansion President Shavkat Mirziyoyev and Prime Minister Takaichi signed wide-ranging agreements in education, healthcare, environment, water, transport, urban development, agriculture, and disaster preparedness. Key priorities included green energy, IT, critical minerals, mechanical engineering, and healthcare modernization. Japan committed yen-denominated loans, medical equipment grants, and investment support for MSMEs. A project portfolio worth over $12 billion was announced, and both sides agreed to create a joint investment platform and a special economic zone in Samarkand modeled on Japanese standards. The scaling-up of the “One Village, One Product” initiative was also supported. Japan and Uzbekistan, which have cooperated in education since the early 1990s, plan to open a joint university in Tashkent with Tsukuba University. Tajikistan: Unlocking Potential A Trade and Investment Forum during President Emomali Rahmon’s Tokyo visit attracted over 70 officials and business leaders. The two sides noted the need to shift from isolated projects to a systemic investment strategy. Tajikistan emphasized its favorable business climate and openness to Japanese participation in infrastructure, energy, and high-tech sectors. An intergovernmental agreement was signed on mutual investment protection. JICA has played a key role in Tajikistan since 2006, supporting development in water, transport, education, and more. Bilateral trade exceeded $109 million in 2024. Kazakhstan: Resources and Logistics Hub President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev held high-level talks with Prime Minister Takaichi and business leaders from Mitsui, Rakuten, Sumitomo, Komatsu, Hitachi, and the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security. Over 60 agreements totaling $3.7 billion were signed. Kazakhstan, which supplies uranium, rare earth metals, and oil to Japan, received more than $8.5 billion in Japanese investments. Trade between the two countries reached approximately $2 billion in 2024. Japan will help modernize customs procedures at the port of Aktau and participate in infrastructure development along the Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian route). More than 80% of land freight between Asia and Europe currently passes through Kazakhstan. Energy Projects and Future Cooperation Kazakhstan’s natural resources and Japan’s nuclear expertise offer opportunities for cooperation in energy innovation, safety, waste management, and personnel training. The region’s reserves of rare earth elements make it a potential hub in the global energy transition. The SmartMining Plus project, focused on digitalization and sustainability in mining, is already underway. Diplomatic relations between Kazakhstan and Japan date back to 1992. Over 60 Japanese firms now operate in Kazakhstan across sectors such as energy, mining, finance, medicine, and logistics. Expert Assessment According to Timur Dadabaev, professor at Tsukuba University, the summit marks a shift from quiet diplomacy to a strategic institutional partnership. It strengthens Central Asia’s multi-vector diplomacy and embeds Japan’s long-term presence. Tajik analyst Sobir Kurbanov noted the increased significance of Central Asia in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Japan’s access to critical resources, including rare earth metals, is a key strategic interest. Japan faces stiff competition from Russia, China, the European Union, and the U.S., but its image as an innovative, non-imperial partner gives it a unique edge. Kazakh political scientist Dosym Satpayev noted that Japan’s trade with Central Asia, about $35 billion, is higher than that of the U.S., though it trails China’s $95 billion and the EU’s $50 billion with Kazakhstan alone. Kazakhstan remains Japan’s primary regional partner, mostly supplying raw materials.

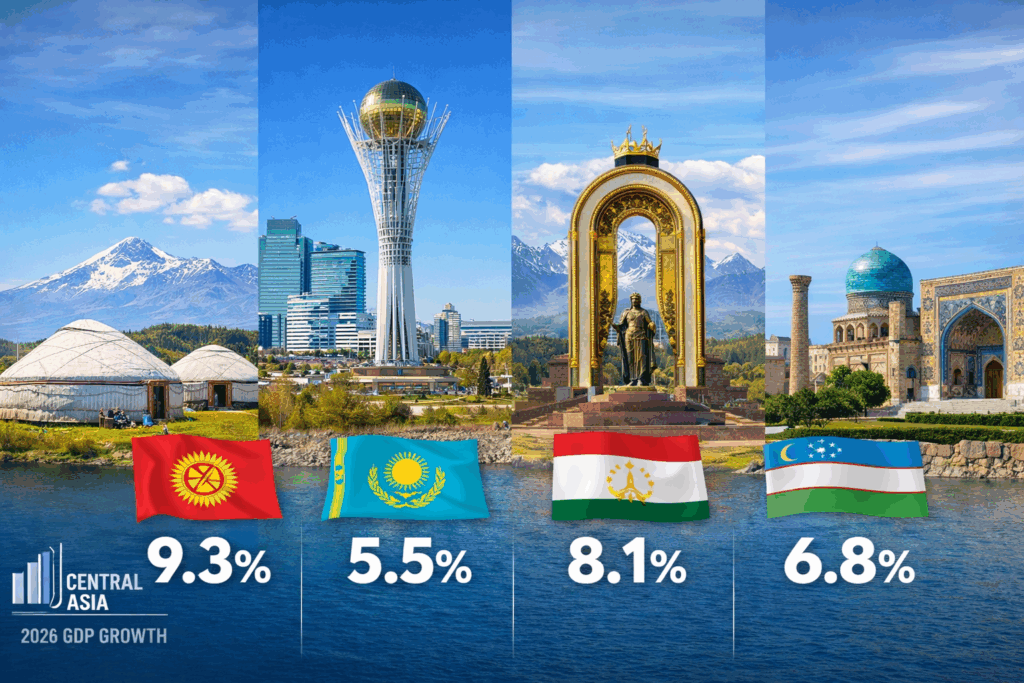

EDB Forecasts Strong Economic Growth in 2026 for Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan

On December 18, the Eurasian Development Bank (EDB) published its Macroeconomic Outlook for 2026-2028, reviewing recent economic developments and offering projections for its seven member states: Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. According to the report, aggregate GDP growth across the EDB region is forecast to reach 2.3% in 2026. Kyrgyzstan (9.3%), Tajikistan (8.1%), Uzbekistan (6.8%), and Kazakhstan (5.5%) are expected to remain the region’s fastest-growing economies. After two years of rapid expansion, the region’s GDP growth is set to moderate to 1.9% in 2025, down from 4.5% in 2024, mainly due to a slowdown in Russia’s economy. Although lower oil prices are expected to reduce export revenues for energy exporters such as Kazakhstan and Russia, the impact on overall growth will be limited. Meanwhile, net oil importers, including Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, will benefit from improved terms of trade and reduced inflationary pressure. High global gold prices will support foreign exchange earnings for key regional exporters, including Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. The report also notes a gradual decline in the U.S. dollar’s share in central bank reserves across the region, though its role in international settlements remains stable. Kazakhstan Kazakhstan’s economy is projected to grow by 5.5% in 2026, supported by the implementation of the National Infrastructure Plan and the state program “Order for Investment,” which are expected to cushion the effects of lower oil prices. Growth in non-commodity exports will also play a stabilizing role. Inflation is forecast to decline to 9.7% by the end of 2026, after peaking early in the year due to a value-added tax (VAT) increase. The average tenge exchange rate is expected to be KZT 535 per U.S. dollar, underpinned by a high base interest rate and rising export revenues. Kyrgyzstan Kyrgyzstan is forecast to lead the region in GDP growth at 9.3% in 2026, driven by higher investment in transport, energy, water infrastructure, and housing construction. Inflation is expected to ease to 8.3%, although further declines will be constrained by higher tariffs and excise taxes. The average exchange rate is projected at KGS 89.2 per U.S. dollar, supported by robust remittance inflows and high global gold prices, gold being the country’s main export commodity. Tajikistan Tajikistan is projected to maintain high GDP growth of 8.1% in 2026, fueled by capacity expansion in the energy and manufacturing sectors, along with rising prices for gold and non-ferrous metals. Inflation is expected to reach 4.5% by year-end. The somoni is expected to remain stable, with an average exchange rate of TJS 9.8 per U.S. dollar, supported by growth in exports and remittances. Uzbekistan Uzbekistan’s economy is forecast to expand by 6.8% in 2026, sustained by strong investment activity and favorable gold prices. Inflation is projected to decline to 6.7%, helped by tight monetary policy and a stable exchange rate. The average soum exchange rate is expected to be UZS 12,800 per U.S. dollar, supported by high remittances and increased metal exports.

Sunkar Podcast

Central Asia and the Troubled Southern Route