New U.S. Ambassador to Kazakhstan to Build “Momentum” on Trade, Diplomacy

Julie Stufft, the new U.S. ambassador to Kazakhstan, is a career diplomat who has said her goal is to ensure that U.S. companies in the Central Asian country have not just an “even playing field” but are also “the partners of choice” in a region where Russia and China are the dominant trading partners. Stufft, who made those remarks during her confirmation hearing in the U.S. Congress in July, presented her credentials to President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev of Kazakhstan in Astana on Friday. She has previously worked on COVID-19 travel policies and U.S. visa processing worldwide and was most recently deputy assistant to the president and executive secretary of the National Security Council. Stufft has served as deputy chief of mission in the U.S. Embassies in Moldova and Djibouti, and was also a diplomat in Russia, Ethiopia, and Poland. One of Stufft’s daughters, Nora, is a student at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado. After the credentials ceremony in Astana, Stufft said Tokayev and U.S. President Donald Trump have a “very close relationship” and that there was impetus for further collaboration between Kazakhstan and the United States. “We have so much momentum from President Tokayev´s recent visit to Washington that we have to build on this,” Stufft said in reference to a November summit hosted by Trump and attended by the leaders of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The meeting focused on securing big trade deals as well as U.S access to minerals in Central Asia that are critical to energy and other industries. Another U.S. goal is to counter the longstanding influence of Russia and China in Central Asian countries, whose leaders seek to balance their relationships with the big powers. Last month, in another round of diplomatic outreach, Trump invited Tokayev and President Shavkat Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan to attend the G20 summit in Miami later this year. In addition to holding large reserves of critical minerals, Kazakhstan is a top uranium producer and a major oil exporter. China and Russia are its biggest overall trading partners. While U.S. trade with Kazakhstan is relatively small in comparison, the relationship is growing. “My goal as ambassador, if confirmed, would be to make sure that U.S. companies have an even playing field so that they can do investment in Kazakhstan, and also that U.S. companies are the partners of choice in Kazakhstan, instead of Chinese or other companies,” Stufft said in her confirmation hearing last year. The previous U.S. ambassador to Kazakhstan, Daniel Rosenblum, resigned from the post in January 2025.

Pannier and Hillard’s Spotlight on Central Asia: New Episode Available Sunday

As Managing Editor of The Times of Central Asia, I’m delighted that, in partnership with the Oxus Society for Central Asian Affairs, from October 19, we are the home of the Spotlight on Central Asia podcast. Chaired by seasoned broadcasters Bruce Pannier of RFE/RL’s long-running Majlis podcast and Michael Hillard of The Red Line, each fortnightly instalment will take you on a deep dive into the latest news, developments, security issues, and social trends across an increasingly pivotal region. This week, the team is taking a deep dive into the worsening situation for Central Asian migrant laborers in Russia, as seen in the recent raid in Khabarovsk, where one Uzbek citizen was beaten to death, and another was left in a coma. Our guest is Tolkun Umaraliev, the regional director for RFERL's Central Asian service and previously the head of RFERL's Migrant Media project.

Orthodox Christmas in Central Asia Highlights Faith, Tradition, and Tolerance

On January 7, Orthodox Christians in Central Asia and around the world celebrate Christmas. In the region, the holiday has become a symbol of religious and ethnic tolerance. Christmas is one of the most significant holidays for believers and is also cherished by many who are not religious. It is celebrated by billions globally. However, the majority of Orthodox Christians and Catholics do not observe Christmas on the same day.

While Christmas falls on January 7 for millions of Orthodox Christians in Central Asia, the holiday is marked not only by church services but also by official recognition, public celebrations, and interfaith messages—underscoring the region’s emphasis on religious coexistence.

In the early centuries of the Christian era, the Julian calendar was used universally, but, over time, astronomers found that the Julian calendar miscalculated the solar year’s length. As a result, it was replaced by the more accurate Gregorian calendar, which is now followed in most of the secular world. However, many Orthodox churches did not adopt the Gregorian reform. Consequently, many Orthodox Christians celebrate Christmas not on December 25, but 13 days later, on January 7.

Some interpreters of church law argue that the Julian calendar is sanctified by centuries of tradition. The Russian Orthodox Church, in particular, maintains that transitioning to the Gregorian calendar would violate canonical norms.

A Bright Holiday in Kazakhstan

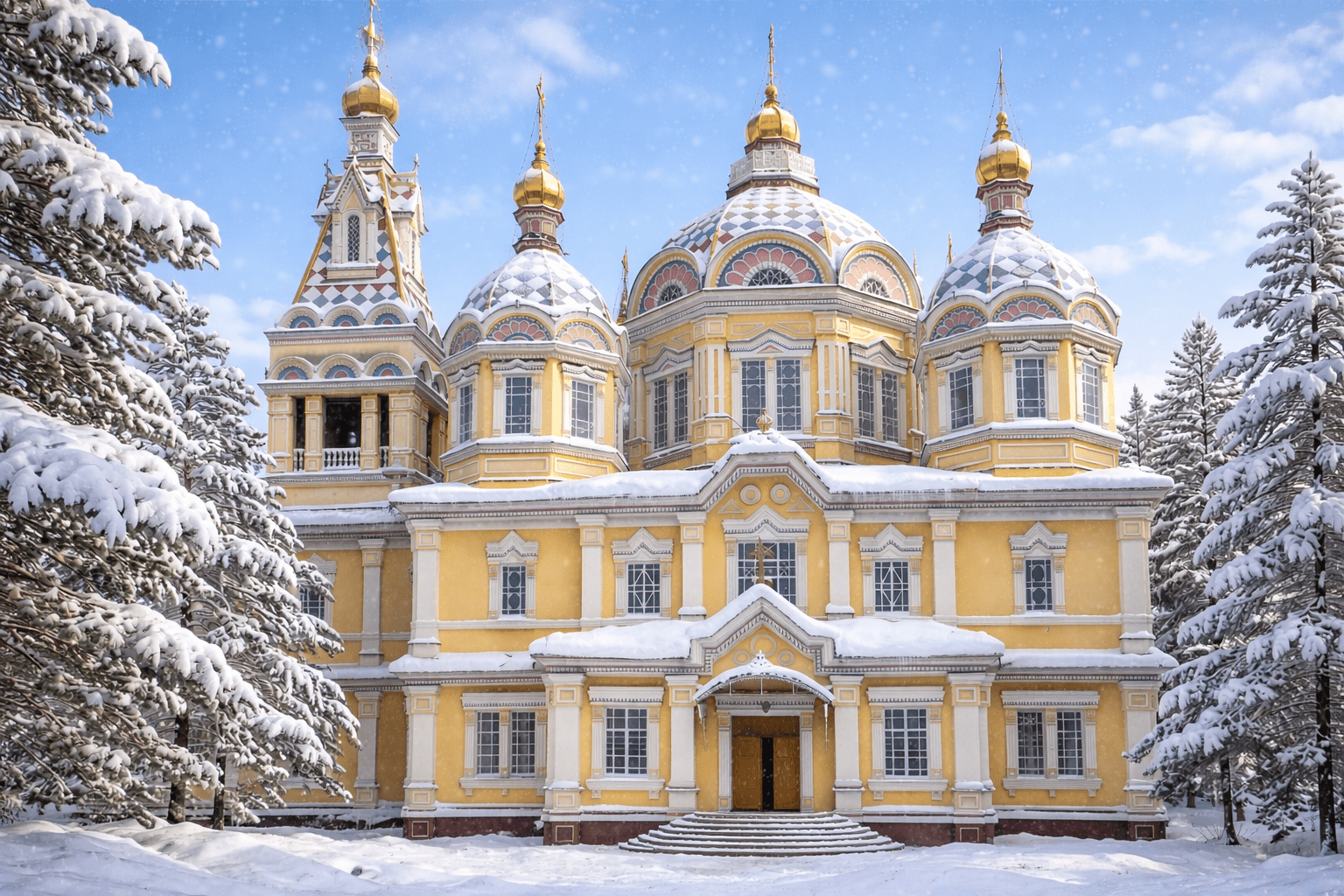

In Kazakhstan, the Ascension Cathedral in Almaty is filled with worshippers on Christmas Eve. The cathedral is a spiritual, historical, and cultural landmark of the country.

[caption id="attachment_41873" align="aligncenter" width="1536"] The Zenkov (Ascension) Cathedral, Almaty; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

This year, Metropolitan Alexander, head of the Orthodox Church in Kazakhstan, conducted the divine liturgy at the cathedral, urging people to mark the holiday through acts of kindness.

“It would be wrong to celebrate Christmas if we do not share this joy with our neighbors, especially those in need of comfort and support. Let us strive to make this festive season truly bright and solemn for all of us, through good deeds, words of comfort and encouragement, compassion, and mercy. Let us extend a helping hand to those who mourn, encourage those who are discouraged, visit those who are sick, and remember those who are lonely,” said Metropolitan Alexander of Astana and Kazakhstan.

In Astana, Bishop Gennady of Kaskelen, administrator of the Metropolitan District, offered Christmas greetings and led a service at Uspensky Cathedral. Orthodox Christmas is a public holiday in Kazakhstan. Representatives of various faiths have emphasized that the day symbolizes peaceful coexistence among people of different nationalities and religions.

Christmas Carols and Religious Freedom

In Uzbekistan, Metropolitan Vikenty of Tashkent and Uzbekistan, head of the Central Asian Metropolitan District, led the Divine Liturgy at the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Tashkent. The Orthodox community in Uzbekistan is estimated to number between 600,000 and a million. Religious observers note that the public celebration of Orthodox Christmas across Central Asia increasingly reflects a broader emphasis on social stability, interfaith dialogue, and state support for religious expression.

[caption id="attachment_41874" align="aligncenter" width="1280"]

The Zenkov (Ascension) Cathedral, Almaty; image: TCA, Stephen M. Bland[/caption]

This year, Metropolitan Alexander, head of the Orthodox Church in Kazakhstan, conducted the divine liturgy at the cathedral, urging people to mark the holiday through acts of kindness.

“It would be wrong to celebrate Christmas if we do not share this joy with our neighbors, especially those in need of comfort and support. Let us strive to make this festive season truly bright and solemn for all of us, through good deeds, words of comfort and encouragement, compassion, and mercy. Let us extend a helping hand to those who mourn, encourage those who are discouraged, visit those who are sick, and remember those who are lonely,” said Metropolitan Alexander of Astana and Kazakhstan.

In Astana, Bishop Gennady of Kaskelen, administrator of the Metropolitan District, offered Christmas greetings and led a service at Uspensky Cathedral. Orthodox Christmas is a public holiday in Kazakhstan. Representatives of various faiths have emphasized that the day symbolizes peaceful coexistence among people of different nationalities and religions.

Christmas Carols and Religious Freedom

In Uzbekistan, Metropolitan Vikenty of Tashkent and Uzbekistan, head of the Central Asian Metropolitan District, led the Divine Liturgy at the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Tashkent. The Orthodox community in Uzbekistan is estimated to number between 600,000 and a million. Religious observers note that the public celebration of Orthodox Christmas across Central Asia increasingly reflects a broader emphasis on social stability, interfaith dialogue, and state support for religious expression.

[caption id="attachment_41874" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Tashkent[/caption]

For believers, the ability to freely celebrate Christmas is seen as a sign of social stability. In February 2025, Uzbekistan adopted a new policy framework for ensuring freedom of conscience and guiding state policy in the religious sphere. The Bible Society of Uzbekistan welcomed the initiative, describing it as vital for fostering interfaith dialogue and upholding the principles of a secular state.

In Kyrgyzstan, a festive service was held at the Holy Resurrection Cathedral and the Church of St. Vladimir, Equal to the Apostles, in Bishkek.

Throughout Central Asia, Orthodox Christmas is traditionally celebrated with a festive meal. At the center of the holiday table is kutya (or sochivo), a dish made from wheat grains, nuts, honey, dried fruit, and poppy seeds. It symbolizes prosperity, family unity, and eternal life.

[caption id="attachment_41877" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Tashkent[/caption]

For believers, the ability to freely celebrate Christmas is seen as a sign of social stability. In February 2025, Uzbekistan adopted a new policy framework for ensuring freedom of conscience and guiding state policy in the religious sphere. The Bible Society of Uzbekistan welcomed the initiative, describing it as vital for fostering interfaith dialogue and upholding the principles of a secular state.

In Kyrgyzstan, a festive service was held at the Holy Resurrection Cathedral and the Church of St. Vladimir, Equal to the Apostles, in Bishkek.

Throughout Central Asia, Orthodox Christmas is traditionally celebrated with a festive meal. At the center of the holiday table is kutya (or sochivo), a dish made from wheat grains, nuts, honey, dried fruit, and poppy seeds. It symbolizes prosperity, family unity, and eternal life.

[caption id="attachment_41877" align="aligncenter" width="800"] Kutya[/caption]

Like Catholic and Protestant Christmas, Orthodox Christmas is viewed as a time of miracles. Christmas trees remain decorated in homes after New Year’s, and the celebratory mood continues. On Christmas Eve, Orthodox Christians often go caroling. After the church service, young people dress in costumes and visit neighbors, singing songs that offer wishes of health and happiness. Hosts typically offer them food and drink. Today, this custom is often performed theatrically and can even be seen in public places such as supermarkets.

Many folk beliefs and superstitions are also tied to the holiday. For example, families observe who first crosses the threshold of the home on the morning of January 7. If it is a man, the household is believed to be blessed with good luck and prosperity for the year. Christmas also typically marks the onset of a cold snap in Central Asia, which continues until the holiday of Epiphany.

Observed across borders and traditions, Orthodox Christmas in Central Asia blends faith, folklore, and public life, serving both as a sacred celebration and a reflection of the region’s diverse religious fabric.

Kutya[/caption]

Like Catholic and Protestant Christmas, Orthodox Christmas is viewed as a time of miracles. Christmas trees remain decorated in homes after New Year’s, and the celebratory mood continues. On Christmas Eve, Orthodox Christians often go caroling. After the church service, young people dress in costumes and visit neighbors, singing songs that offer wishes of health and happiness. Hosts typically offer them food and drink. Today, this custom is often performed theatrically and can even be seen in public places such as supermarkets.

Many folk beliefs and superstitions are also tied to the holiday. For example, families observe who first crosses the threshold of the home on the morning of January 7. If it is a man, the household is believed to be blessed with good luck and prosperity for the year. Christmas also typically marks the onset of a cold snap in Central Asia, which continues until the holiday of Epiphany.

Observed across borders and traditions, Orthodox Christmas in Central Asia blends faith, folklore, and public life, serving both as a sacred celebration and a reflection of the region’s diverse religious fabric.

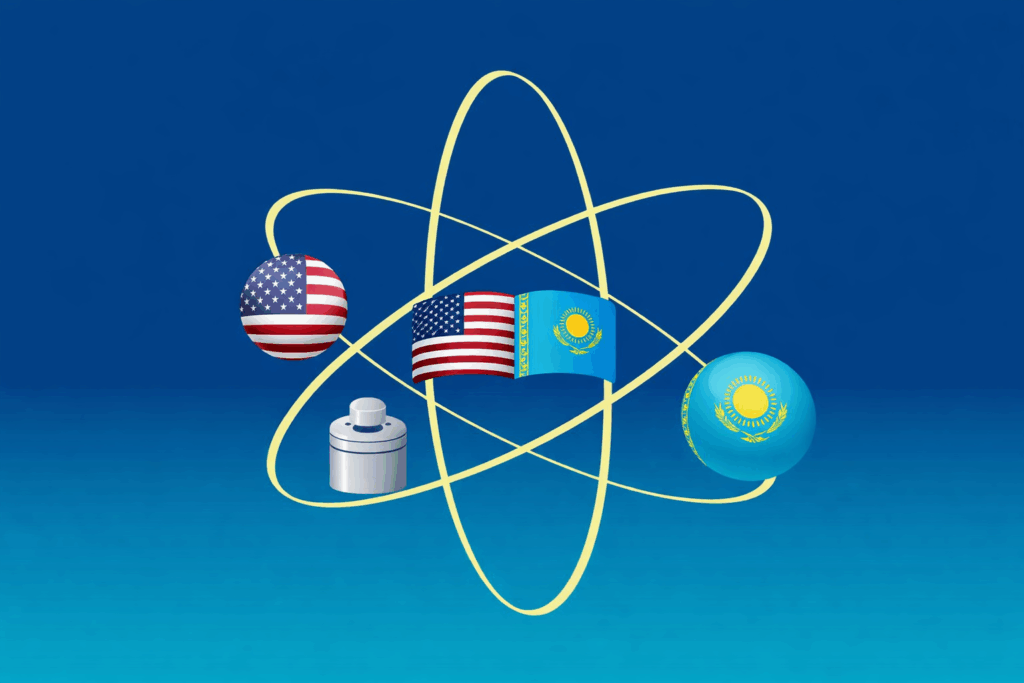

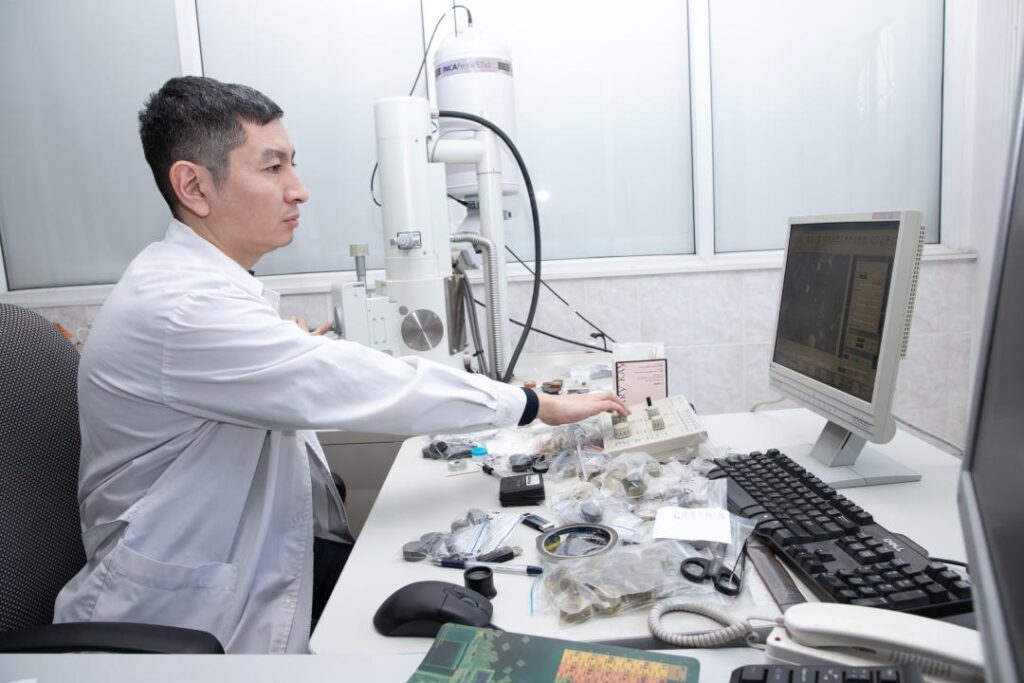

U.S. and Kazakhstan Expand Civil Nuclear Cooperation With Focus on Small Modular Reactors

The United States and Kazakhstan have expanded cooperation on civil nuclear energy, placing small modular reactors at the center of a new phase in bilateral engagement. In late December 2025, the U.S. Embassy in Kazakhstan announced two initiatives under the U.S. State Department’s Foundational Infrastructure for Responsible Use of Small Modular Reactor Technology program, known as FIRST. The measures focus on workforce training and technical evaluation as Kazakhstan prepares to reintroduce nuclear power generation. Kazakhstan is the first country in Central Asia to participate in the FIRST program, which was launched by the U.S. State Department in 2021 to help partner countries prepare regulatory frameworks, workforce capacity, and infrastructure for advanced nuclear technologies. The first initiative provides for the installation of a classroom-based SMR (small modular reactor) simulator at the Kazakhstan Institute of Nuclear Physics in Almaty. The simulator is intended to train specialists in reactor operations, safety systems, and emergency response. On January 6, 2026, the American Nuclear Society reported that the simulator will be supplied by U.S. companies Holtec International and WSC Inc., a simulation technology company that operates as part of the Curtiss-Wright group. The project is designed to build domestic technical capacity prior to licensing or construction decisions. The International Science and Technology Center is supporting implementation in Kazakhstan. The second initiative is a feasibility study examining which U.S.-designed SMRs could be technically and economically suitable for Kazakhstan. According to the American Nuclear Society, the study is being conducted under FIRST, with U.S. engineering firm Sargent & Lundy. The assessment is expected to cover grid integration, siting considerations, cooling requirements, and indicative deployment timelines. The study does not authorize construction or commit Kazakhstan to a specific reactor technology; rather, the feasibility study is intended to produce a shortlist of U.S. SMR designs that could be compatible with Kazakhstan’s grid, geography, and projected electricity demand. These initiatives follow Kazakhstan’s decision to return to nuclear power. On October 6, 2024, voters approved the construction of nuclear power plants in a national referendum. Official results published by the Central Referendum Commission showed 71.12% voting in favor, with turnout at 63.66%. Kazakhstan has not generated nuclear electricity since the BN-350 fast reactor at Aktau was shut down in 1999. Government energy planners have warned that Kazakhstan faces growing electricity shortfalls as early as the mid-2020s, driven by aging coal plants and rising consumption. Kazakhstan’s interest in nuclear energy reflects structural pressures in the power sector. Coal-fired plants still supply most electricity, particularly in northern regions, but much of that capacity is aging. Electricity demand continues to rise alongside industrial output and urban growth, while the government has set targets to reduce emissions intensity. Nuclear power is being positioned as a source of stable, low-carbon baseload generation that can complement renewable energy. Kazakhstan also occupies a central position in the global nuclear fuel market. The country accounts for about 40% of global uranium mine production and holds roughly 14% of identified recoverable uranium resources. Despite that role, the country has relied on fossil fuels for domestic electricity generation for more than two decades, a situation characterized by President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev in a January 5 interview as a “historical absurdity”. Tokayev has repeatedly argued that Kazakhstan’s status as the world’s leading uranium producer strengthens the economic and strategic case for domestic nuclear power generation. Large-scale reactors remain the core of Kazakhstan’s near-term nuclear plans. In 2025, Kazakhstan selected Russia’s Rosatom to build its first nuclear power plant at Ulken, near Lake Balkhash, using two VVER-1200 reactors. Kazakhstan has also moved forward with plans for a second nuclear power plant to be built by China’s China National Nuclear Corporation, reflecting a broader multi-vector nuclear diplomacy strategy. Officials have presented SMRs as a complementary option that could serve industrial sites or regions not immediately connected to large new nuclear plants. The U.S.-supported SMR initiatives operate on a different timeline. SMRs are generally defined as reactors producing up to 300 megawatts of electricity per unit and are promoted for their modular construction and potential flexibility in deployment. No U.S. SMR has yet entered commercial operation, but several designs are advancing through licensing and demonstration. The FIRST program focuses on regulatory readiness, workforce development, and early technical planning rather than financing or construction. For Kazakhstan, participation in FIRST adds a U.S. component to its nuclear strategy. The simulator and feasibility study expand technical expertise and provide comparative data that could inform future decisions on reactor scale and deployment. The initiatives broaden the range of technologies under consideration as nuclear power returns to a central place in Kazakhstan’s long-term energy strategy.

The Venezuela Effect: Oil, Sanctions, and Kazakhstan’s Strategic Dilemma

The start of 2026 was marked by political upheaval across two continents: fresh protests in Iran drawing comparisons among some Kazakh analysts to the country’s own Bloody January of 2022, and a U.S. military operation described by Washington as a law-enforcement action in Venezuela. The latter led to the arrest of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and what some analysts are describing as a move toward far greater U.S. influence over Venezuela’s oil sector. Beyond its immediate implications for global oil supply and pricing, the geopolitical symbolism of the Venezuela operation is resonating in unexpected places, including Central Asia. Contrary to some early reports, the American intervention in Caracas was not bloodless. At least 40 Venezuelan security and military personnel were reportedly killed during the rapid offensive. Still, Kazakh political scientist Marat Shibutov argues that the perception of a swift and decisive U.S. action, especially in contrast to Russia’s grinding war in Ukraine, is symbolically damaging for Moscow. “This comparison with Russia’s prolonged conflict is not flattering,” Shibutov noted. “It creates a sensitive political backdrop for the Kremlin.” In Kazakhstan, where debates over foreign energy contracts have been simmering for years, the events in Venezuela are being closely watched. Political analyst Daniyar Ashimbayev referenced Astana’s past discussions about reviewing oil agreements with Western companies. “The topic of revising oil contracts is becoming less and less popular. At this rate, it could even be equated with extremism,” he commented ironically, underscoring how sensitive the issue has become. Some experts are also concerned that political shifts in Venezuela and Iran could destabilize the oil market in ways that would hit Kazakhstan’s economy hard. Kazakhstan derives a substantial share of its state budget revenues from the oil sector, making sustained price declines a direct fiscal risk rather than a purely market concern, analysts note. Energy analyst Olzhas Baidildinov points out that Venezuela holds the largest proven oil reserves in the world, approximately 300 billion barrels, more than 30 times Kazakhstan’s profitable reserves. “If liberal or Western-friendly governments come to power simultaneously in Venezuela and Iran, they could supply an additional 2-3 million barrels per day to the global market within the next 3-4 years,” he warned. Even without full regime change, he noted, easing sanctions or the return of “shadow exports” could push global prices down to $50-70 per barrel. “At such prices, it will be difficult to demonstrate economic growth and maintain momentum in Kazakhstan’s oil sector,” Baidildinov added. Financial analyst Arman Beisembayev offered a more bearish view. “If production volumes increase and the U.S. begins releasing more oil onto the market, including from Venezuela, then I’m afraid prices won’t stay at $60 per barrel. The base case is a drop to $50. A worst-case scenario could see prices at $40, or even lower.” But not everyone believes Venezuela can upend the market. Askar Ismailov, a Geneva-based advisor on Central Asia at the Global Gas Centre, remains skeptical. “Venezuelan crude is extremely heavy, difficult to extract, and expensive to transport. Historically, it depended on a complex refining arrangement with U.S. facilities. Rapid production growth is nearly impossible without massive investments and infrastructure overhauls,” he said. Moreover, experts note that American oil firms have little incentive to flood the market, as lower global prices would hurt their own bottom line. Still, geopolitics looms large. Some analysts argue that President Donald Trump may view oil pricing as a strategic lever to pressure the Kremlin into negotiations over Ukraine. If prices fall, Kazakhstan, heavily reliant on oil revenues, could face serious fiscal pressure. That, in turn, may reverberate across Central Asia, where several regional initiatives are underpinned by Kazakh investment. In short, the first days of 2026 have intensified debate among regional analysts, revealing how far-flung crises can ripple through Central Asia’s economic and political landscape.

Kazakhstan Opens Criminal Probe Over Calls to Attack CPC Oil Pipeline

Kazakhstan has opened a criminal investigation into public statements that authorities say encouraged attacks on the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), the main export route for the country’s crude oil, after months of disruption at the system’s Black Sea terminal turned a foreign security risk into a domestic legal and political issue. Prosecutor General Berik Asylov confirmed the case in a written reply to a parliamentary inquiry on January 6. "On December 17, 2025, the Astana City Police Department launched a pre-trial investigation under Part 1 of Article 174 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan (incitement of social, national, tribal, racial, class, or religious discord) into negative public comments regarding damage to the Caspian Pipeline Consortium," the Prosecutor General stated. The authorities have yet to name suspects, publish the posts under review, or announce any arrests. The file remains at the evidence-gathering stage, and prosecutors have left open whether any charges will ultimately be filed under Article 174, or reclassified under other provisions once investigators assess the intent and impact. The probe follows a request by Mazhilis deputy, Aidos Sarym, who said that some social media commentary crossed from opinion into encouragement of harm to strategic infrastructure, endorsed attacks on the CPC, and urged further strikes on critical sites. The political sensitivity is rooted in the 1,500-kilometer pipeline’s central role in Kazakhstan’s economy. CPC carries crude from western Kazakhstan to a marine terminal near Russia’s Black Sea port of Novorossiysk, where the oil is loaded onto tankers for delivery to global markets. The pipeline is owned by a consortium that includes Kazakhstan, Russia, and several international energy companies. The system dominates Kazakhstan’s oil export economy. More than 80% of the country’s crude oil exports move through the CPC route, which also carries more than 1% of global oil supplies, making it a pressure point for both markets and state revenue when operations are disrupted. The investigation follows a period of repeated disruption at the Novorossiysk terminal in late 2025, after a naval drone strike damaged one of the offshore loading points used to transfer oil from the pipeline to tankers. The damage forced operators to suspend loadings and move vessels away while inspections and repairs were carried out, sharply reducing export capacity. The CPC relies on single-point moorings positioned at sea to load crude onto tankers, a critical constraint on the entire system; when one goes offline, capacity drops quickly. The pipeline cannot store large volumes, forcing upstream producers to cut or slow output. By late December, the impact was visible in Kazakhstan’s production figures. Oil output fell by about 6% during the month after the late November strike constrained exports. Production at the Tengiz oilfield, the country’s largest, dropped by roughly 10%. Exports of CPC Blend crude fell to about 1.08 million barrels per day in December, the lowest level in more than a year, as the terminal operated with only one functioning mooring while others remained offline due to damage and maintenance. Operational pressures continued as severe weather in the Black Sea forced further suspensions of loadings toward the end of the month, compounding losses from security incidents and repair delays. By late December, exports through the terminal were running well below November averages. Kazakhstan currently has few alternatives at a comparable scale. Some crude can be diverted through other routes, including links into Russia’s pipeline system or shipments that connect to the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan corridor, but those options are constrained by capacity, logistics, and cost. Even when rerouting is possible, it tends to cover only part of the volume and reduces margins. The repeated disruptions have renewed attention on the Middle Corridor linking Central Asia to Europe via the Caspian Sea and the South Caucasus, but capacity limits, infrastructure gaps, and higher transport costs mean it remains a long-term diversification option rather than a near-term substitute for CPC volumes. The legal basis chosen for the investigation, Article 174 of the criminal code, has long been controversial because of its broad construction and its use in speech-related cases. The provision addresses incitement of social, national, or other forms of discord and has been criticized by legal analysts and rights advocates for its scope. There is precedent for using Article 174 to prosecute speech authorities view as a threat to state stability, but it has typically been applied to cases involving political activism, protest-related rhetoric, or ethnic and religious discourse rather than commentary linked to foreign military actions and economic infrastructure. In the CPC case, the timing suggests the government is moving to deter public rhetoric that could encourage further attacks on infrastructure central to Kazakhstan’s export revenue. The late-2025 disruptions showed how quickly damage to the pipeline system translates into lower output and reduced exports, turning security incidents into measurable economic losses. The diplomatic backdrop adds another layer of sensitivity. With its adherence to a multi-vector foreign policy, Kazakhstan has sought to preserve working relations with both Moscow and Kyiv since Russia invaded Ukraine, while keeping the country out of the conflict and safeguarding trade. After the Novorossiysk incident, Astana framed the terminal as an international civilian facility with global economic significance, while Kyiv said its actions were directed at Russia’s war capacity, not at Kazakhstan. How the case unfolds will determine whether it remains a warning or becomes a precedent. Investigators must identify specific statements, confirm authorship, and assess whether posts amounted to direct calls for violence or remained commentary on reported events. For oil markets and companies operating in Kazakhstan’s upstream sector, the risk remains operational. CPC is still the main export route, and interruptions continue to affect production and shipment forecasts. For domestic politics, the investigation ties enforcement of speech laws to the protection of critical infrastructure at a moment when the economic cost of disruption can be measured in lost barrels and missed export days.

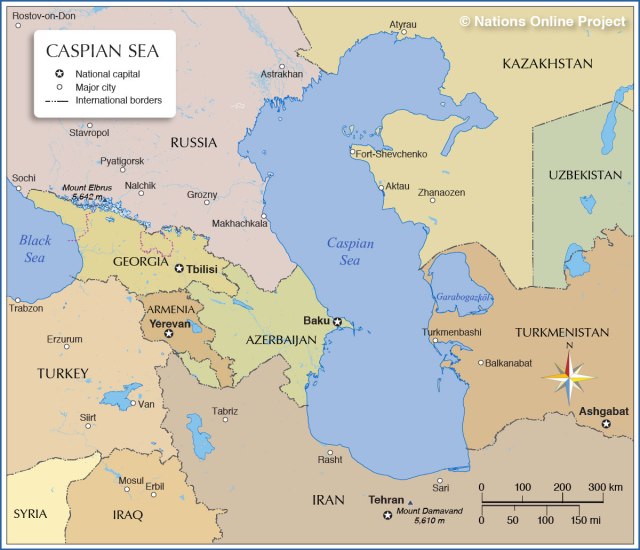

Central Asia Can Depend on Azerbaijan for Path to West, Aliyev Says

Azerbaijan is the only “reliable country” that can geographically link Central Asia to the West because alternative routes face geopolitical turbulence, according to Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev.

Aliyev spoke about Azerbaijan’s prospects as a key conduit for commerce across borders as well as its deepening relationship with Central Asia during a wide-ranging interview with local television channels in Baku on Monday. He acknowledged that there is still work to be done before Azerbaijan can approach its full potential as what he called a “living bridge” for international trade.

The remarks followed a summit in Uzbekistan in November in which Central Asian leaders supported Azerbaijan’s accession to the region’s Consultative Meeting format as a full participant, even though Azerbaijan is in the South Caucasus. The Consultative Meeting format is a vehicle for high-level collaboration on trade, security, and other issues among Central Asian countries, which have taken steps to resolve border disputes and other sources of tension over the years.

“So many projects have been implemented in recent years that these countries have unanimously elected us as a full member. We can also consider this a great political and diplomatic success,” Aliyev said during the interview. His remarks were published by the state Azerbaijani Press Agency, or APA.

Referring to international connectivity, transport, and logistics, the president said, “Azerbaijan is the only reliable country that can geographically connect Central Asia with the West today,” and, without going into specifics, he alluded to the difficulties that some other trade channels face. Paths through Russia and Iran to the West, for example, are affected by sanctions and long-running political tensions.

“Of course, from a geographical point of view, other routes can also be used. However, taking into account the current geopolitical situation, we can say with complete certainty that alternative routes for the West cannot be considered acceptable,” Aliyev said.

He mentioned developing projects such as a November 2024 agreement involving Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan to lay a fiber-optic cable along the Caspian seabed, as well as China’s large-scale funding for the construction of another railway to the Caspian Sea via Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

“Freight traffic to the Caspian Sea, and therefore to Azerbaijan, will increase,” the Azerbaijani president said. “Along with Central Asian countries, additional freight from China will naturally increase the demand for the East–West route, the Middle Corridor.”

A September analysis by the Washington-based Jamestown research group suggested that prospects are bright for Azerbaijan, which has actively positioned itself as a trade hub since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

“Amid disruptions in both the northern and southern corridors, Azerbaijan has emerged as a critical logistics hub, offering a sanction-free, resilient, and stable environment to facilitate overland trade between the PRC (China) and Europe through the Middle Corridor,” analyst Yunis Sharifli wrote.

In addition, Azerbaijan expects cargo from China and Central Asia to travel along a proposed route that would link the main part of Azerbaijan to the separate Azerbaijani area of Nakhchivan, passing through Armenia and then joining with Türkiye and European markets beyond. Such a link would make land trade between East Asia and Europe more efficient, though Armenia is concerned that the plan threatens its sovereignty.

In August, Aliyev and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan met in Washington with U.S. President Donald Trump acting as a mediator in the peace initiative between the former battlefield foes.

“So many projects have been implemented in recent years that these countries have unanimously elected us as a full member. We can also consider this a great political and diplomatic success,” Aliyev said during the interview. His remarks were published by the state Azerbaijani Press Agency, or APA.

Referring to international connectivity, transport, and logistics, the president said, “Azerbaijan is the only reliable country that can geographically connect Central Asia with the West today,” and, without going into specifics, he alluded to the difficulties that some other trade channels face. Paths through Russia and Iran to the West, for example, are affected by sanctions and long-running political tensions.

“Of course, from a geographical point of view, other routes can also be used. However, taking into account the current geopolitical situation, we can say with complete certainty that alternative routes for the West cannot be considered acceptable,” Aliyev said.

He mentioned developing projects such as a November 2024 agreement involving Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan to lay a fiber-optic cable along the Caspian seabed, as well as China’s large-scale funding for the construction of another railway to the Caspian Sea via Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

“Freight traffic to the Caspian Sea, and therefore to Azerbaijan, will increase,” the Azerbaijani president said. “Along with Central Asian countries, additional freight from China will naturally increase the demand for the East–West route, the Middle Corridor.”

A September analysis by the Washington-based Jamestown research group suggested that prospects are bright for Azerbaijan, which has actively positioned itself as a trade hub since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

“Amid disruptions in both the northern and southern corridors, Azerbaijan has emerged as a critical logistics hub, offering a sanction-free, resilient, and stable environment to facilitate overland trade between the PRC (China) and Europe through the Middle Corridor,” analyst Yunis Sharifli wrote.

In addition, Azerbaijan expects cargo from China and Central Asia to travel along a proposed route that would link the main part of Azerbaijan to the separate Azerbaijani area of Nakhchivan, passing through Armenia and then joining with Türkiye and European markets beyond. Such a link would make land trade between East Asia and Europe more efficient, though Armenia is concerned that the plan threatens its sovereignty.

In August, Aliyev and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan met in Washington with U.S. President Donald Trump acting as a mediator in the peace initiative between the former battlefield foes.

Tokayev Sets Agenda for Kazakhstan’s 2026 EAEU Chairmanship

Kazakhstan has assumed the rotating chairmanship of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) for 2026, pledging to focus on digital transformation, logistics integration, and the removal of internal trade barriers across the bloc. In a statement published on December 31, 2025, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev outlined five key priorities for Kazakhstan’s EAEU presidency. The EAEU includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia, and facilitates the free movement of goods, services, capital, and labor among its members. Artificial Intelligence and Economic Integration Tokayev identified artificial intelligence (AI) as a vital tool for deepening integration within the bloc. AI technologies, he said, are already being used to forecast trade flows and assess the impact of tariffs and trade agreements on member economies. Kazakhstan, which has set a national goal of becoming a digital nation, expressed readiness to share its expertise with other EAEU members in areas such as AI, digital regulation, and economic transformation. Tokayev proposed the adoption of a Joint Statement on the Responsible Development of Artificial Intelligence at the 2026 Eurasian Economic Forum in Astana. The document would define a new framework for digital cooperation within the bloc. Positioning the EAEU as a Eurasian Logistics Hub Highlighting the EAEU’s geographic position as a natural bridge between East and West, Tokayev called for transforming the bloc into a leading logistics hub for the Eurasian continent. He emphasized the need to modernize transport, customs, and logistics infrastructure, and to develop international transport corridors and multimodal transport solutions. He also proposed an integrated, AI-based cargo flow management system across the EAEU to reduce delivery times, cut costs, and enhance the bloc’s global competitiveness in logistics. Digitalizing Industry and Agriculture Calling industry and agriculture the economic foundation of the EAEU, Tokayev urged deeper cooperation to produce globally competitive products. While financial mechanisms for joint projects already exist, he argued that more emphasis should be placed on innovation-led initiatives. He proposed launching demonstration centers, automation startups, and competence hubs to drive digitalization at both enterprise and farm levels. Barrier-Free Trade as a Core Principle Tokayev stressed the elimination of administrative and regulatory barriers within the bloc as a central priority. He criticized artificial restrictions on trade, constraints on the movement of citizens, and long freight queues at borders. He also warned against the use of customs procedures and regulatory controls, including sanitary, veterinary, and phytosanitary measures, as tools of political or economic leverage. To address this, he proposed deploying AI to monitor legislative initiatives across the EAEU and flag potential internal trade barriers at an early stage. Expanding External Economic Ties Kazakhstan’s chairmanship will also focus on expanding the EAEU’s external partnerships. In 2025, the bloc signed Free Trade Area agreements with Mongolia and Indonesia and concluded an Economic Partnership Agreement with the United Arab Emirates. Tokayev said greater attention will be paid to building economic ties with countries in the Global South, the Arab world, Southeast Asia, Africa, and regional economic organizations. Macroeconomic Context Tokayev’s agenda is being launched against a backdrop of solid macroeconomic performance across the EAEU. According to Alexey Vedev, Director of the Macroeconomic Policy Department at the Eurasian Economic Commission, the bloc’s GDP grew by 17.8%, nearly $1 trillion in absolute terms between 2015 and 2024. The EAEU’s share of the global economy rose from 3.7% to 4.1%, with member state growth rates surpassing the global average in recent years. Summing up Kazakhstan’s vision, Tokayev said the country would work to strengthen the effectiveness, relevance, and long-term viability of Eurasian economic integration during its 2026 chairmanship.

Sunkar Podcast

Central Asia and the Troubled Southern Route